By Matthew C. Hulbert

On November 2, 1865, a petition arrived on the desk of Governor Thomas E. Bramlette. Two men from Wayne County, Granville Ingram and Levi Baker, each faced a $100 fine for “tipling.” (That is, for dealing in unlicensed liquor.) Relative to modern legal standards, it’s common to assume that alcohol restrictions were lax in the 1860s—if not altogether nonexistent. In fact, before proceeding with our story, it’s worth taking a moment to note that the production, sale, and consumption of distilled spirits in Kentucky were heavily regulated in the 1860s, almost as much as they are today. Even as the Civil War raged around them, scores of civilians found themselves in court for various liquor-related offenses: unlicensed distilling, unlicensed sale, selling in the wrong unit or quantity, selling liquor to minors, being drunk on duty, and a wide array of more violent, booze-fueled crimes ranging from arson and assault to homicide. (More on this in next week’s blogging.)

It would be easy, then—and admittedly more exciting—to imagine Ingram and Baker as something like the Popcorn Suttons of their day; small-time operators who defied the law to provide their customers with the oldest variety of old school Kentucky whiskey. In reality, though, they were legitimate salesmen; they had a pretty good excuse for their fines and, more important still, a very influential lawyer on their side.

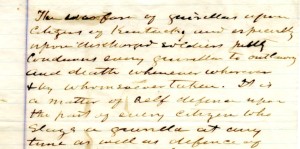

As Bramlette scanned the petition, he would have immediately noticed that Ingram and Baker had “applied to and obtained from the Government of the United States a license in due form and paid the tax thereon.” Reading further, it would have become evident that the state’s own inability to function properly at war had contributed more to the conviction of Ingram and Baker than any true criminal mischievousness.

That they would also have obtained a license from the Trustees of Monticello and paid the tax thereon to the Corporation and to the state, but during the time they operated under the license from the general government, there were no trustees in Office, and Consequently they were unable to procure Corporation license. They state that they had no intention of violating any law or defrauding the state or Corporate authority, And moreover they carried on the business at the time of the invasion of this portion of the state by Rebels, and at the time law and Order was unknown in this section of the County.

In layman’s terms, Ingram and Baker had obtained the license required of them to sell whiskey by the federal government—but they also needed local and state licenses. (This likely means they were selling to the Union army; federal customers required federal licensing.) Owing to the aforementioned “invasion,” those local and state licenses were not readily available for purchase. As you can imagine, county clerks didn’t tend to hold fast and defend their posts when enemy forces, regular or guerrilla, arrived in town.

These things considered, Ingram and Baker implored Bramlette to “release them from the payment of that portion of the fines to which the State is entitled. In return, they even promised “not [to] annoy your Excellency with such importunities for the future.” Several citizens of Wayne County supported the petition, but none were more important than John Sallee Van Winkle, an attorney in Wayne County and the brother of Ephraim L. Van Winkle (then Kentucky’s secretary of state). Toward the end of the document, J. S. Van Winkle signed and insisted that “there can be no doubt but the remission asked is proper & should be granted.” Bramlette heeded his advice; the fines were remitted on November 13, 1865.

Ultimately, this case underscores how difficult it was for the state to maintain its civilian responsibilities during the war, but should also remind us that life didn’t simply pause on the homefront until the conflict concluded. The wheels of local and state government were expected to keep turning—which, as a result, should have allowed the whiskey to keep flowing. But the archive of The Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition is overrun with tippling and bootlegging cases. The real interest in this story has to do with John Van Winkle and the role his family would play in the future of legal liquor ventures in the Bluegrass State.

In 1866, when E. L. Van Winkle passed away unexpectedly, John was tapped to finish his brother’s term as secretary of state. When the appointment ended, he returned to his law practice, and worked there until his own death in 1888. Given that he and his brother were such luminaries of the state’s legal community, it’s more than a little surprising that John’s son, Julian P. Van Winkle, didn’t follow in their footsteps and study the law. To this day, whether they know it or not, bourbon enthusiasts reap the rewards of his decision.

In 1866, when E. L. Van Winkle passed away unexpectedly, John was tapped to finish his brother’s term as secretary of state. When the appointment ended, he returned to his law practice, and worked there until his own death in 1888. Given that he and his brother were such luminaries of the state’s legal community, it’s more than a little surprising that John’s son, Julian P. Van Winkle, didn’t follow in their footsteps and study the law. To this day, whether they know it or not, bourbon enthusiasts reap the rewards of his decision.

This is because J. P. Van Winkle is better-known as “Pappy”; he is the bespectacled, cigar-puffing old gentleman on the logos of Kentucky’s—and maybe even the world’s—most sought after bottles of bourbon. Today, there are three labels bearing the “Pappy” moniker: Pappy Van Winkle 15 Year, Pappy Van Winkle 20 Year, and Pappy Van Winkle 23 Year. Generally impossible to find on store shelves, they’ve become the stuff of bourbon lotteries and an unprecedented heist in 2012 dubbed “Pappygate.”

Born in 1874 in Danville, Kentucky, Julian worked briefly as a store clerk before finding employ as a salesman at the wholesaling firm of W. L. Weller & Sons. (Yes—that W. L. Weller. He also shows up in the CWG-K archive, but that’s another story for another time.) Eventually Julian became a distiller himself and, after Prohibition, helped oversee operations at the famed Stitzel-Weller facility in Shively, on the outskirts of Louisville. A few years after his death in 1965, most of the S-W labels were sold, but Old Rip Van Winkle remained in the family and charge of the business has passed from generation to generation of Julian Van Winkle’s (Sr.) descendants.

Now to argue that John Van Winkle’s defense of hardworking, but improperly licensed, whiskey peddlers inspired his son to become a bourbon icon would make for an incredible ending to our story. It would also be entirely apocryphal. Julian wasn’t born for a decade after the Ingram-Baker trial and odds are good that he never knew a thing about it. And even if he had, it wouldn’t have stood out. In those days, tippling cases in Kentucky truly were a dime a dozen.

Now to argue that John Van Winkle’s defense of hardworking, but improperly licensed, whiskey peddlers inspired his son to become a bourbon icon would make for an incredible ending to our story. It would also be entirely apocryphal. Julian wasn’t born for a decade after the Ingram-Baker trial and odds are good that he never knew a thing about it. And even if he had, it wouldn’t have stood out. In those days, tippling cases in Kentucky truly were a dime a dozen.

But what he probably did know about, thanks to that wealth of tippling cases and his father’s legal work, was just how complicated and competitive the distilling industry could be, especially for someone just starting out in the business. So the truly remarkable point here isn’t that Julian “Pappy” Van Winkle eschewed a surefire (and no doubt lucrative) career in the family’s legal empire to make bourbon—it’s that in a family once known for powerful Civil War era litigators and secretaries of state, he transformed their empire into making bourbon.

Matthew C. Hulbert is an Assistant Editor of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.

SOURCES: “G. C. Ingram and L. P. Baker to Thomas E. Bramlette,” 2 Nov 1865, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky; 1860 United States Federal Census; 1870 United States Federal Census; 1910 United States Federal Census; 1940 United States Federal Census.