By Matthew C. Hulbert

In October 1863, the Mason Circuit Court (based in Mason County, Kentucky) hit Peter Miller, a legally licensed tavern owner, with maximum fine of $50 for tippling. If this strikes you as odd, it’s because by its very definition in 1863, tippling meant selling alcohol or operating a tavern in which said spirits were sold without a license. Miller balked at the ruling. “I have kept a Bar in Maysville for a number of years,” he noted confidently, “and have always endeavored to comply with the strict letter and spirit of the law.” The fundamental hang-up in the Commonwealth v. Peter Miller, however, was that in this case the letter and spirit of the law actually veered in wildly different directions at the crossroads of slavery.

Chapter 212 of the Acts of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, Passed, Volume I, published in 1856, dealt specifically with the sale of spirituous, malt, or vinous liquors to both slaves and “free negroes.” (Note: the law more or less assumed that all slaves would be African American and thus did not label them “enslaved negroes.”) The statute read as follows:

It shall not be lawful for any person or persons in this commonwealth, either with or without a license, to sell, give, or loan to any slave or slaves, not under his or her control, any spirituous, malt, or vinous liquors, unless it is done upon the written order of the owner or person having the legal control of the service, for the time being, of such slave or slaves; and the written order here meant shall clearly specify the quantity to be sold, given, or loaned, and name the slave or slaves, and shall be dated and signed; and such order shall only be good for the one sale, loan, or gift; and the persons violating the provisions of this act shall be liable to pay the owner not less than twenty nor more than fifty dollars, or to be confined in the jail of the county, where such conviction is had, not less than thirty days nor more than six months, or may be both fined and imprisoned, at the discretion of a jury, for each offense, and also be liable for any actual damage sustained, to be recovered by suit in any court having jurisdiction.

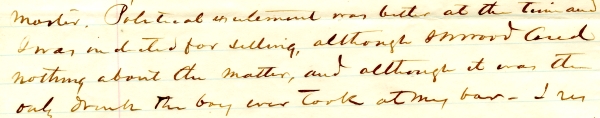

The circumstances of Miller’s case aren’t all that complicated. In fall 1863, a “free negro barber,” Nathaniel Oldham, rented “the negro boy Ed” from a local slave-owner named Samuel W. Wood. And, according to undisputed court testimony, “while thus hired to Oldham, the boy and Oldham his master for the time, drank at Peter Millers bar and purchased from him at the County of Mason upon one occasion, the whiskey & beer drank having been furnished for & paid for by him in the presence of and at the instance of Oldham the free negro to whom he was hired.” So Miller was charged with tippling not for selling without a license, but for selling to someone who wasn’t allowed to be drinking alcohol, licensed or not. The bartender had a sturdy defense: Oldham temporarily owned Ed by virtue of the labor deal with Wood and that as Ed’s temporary master, Oldham held final authority over his chattel’s ability to consume alcoholic beverages. Miller further contended that Ed’s permanent owner, Samuel Wood, “cared nothing about the matter” and that the conviction had only been delivered because “political excitement was bitter at the time.”

The law clearly favored Miller, especially on two points. First, As Ed’s temporary master, Oldham had legal control of Ed’s services and was in a position to legally purchase him liquor (re: “unless it is done upon the written order of the owner or person having the legal control of the service”); and, second, Miller clearly stated that the drinking only occurred once and it doesn’t appear that anyone disputed the assertion in court (re: “and such order shall only be good for the one sale, loan, or gift”).

The elephant in the room, then, is how Peter Miller was ever convicted of anything in the first place?

Our answer here lies not with the letter of the law—but with its spirit. The “political excitement” Miller referenced revolved around the increasingly-tenuous position of slavery in Kentucky. Lincoln’s war aims were changing; the demise of the Peculiar Institution had become a real possibility if the Confederacy faltered now and Conservative Unionists in Kentucky weren’t particularly pleased about it. (If slavery in the Confederacy went, what chance did it have in the nominally-loyal Border States?) So while he’d technically broken no laws in the Commonwealth, by serving two black men in his tavern—one free and openly exhibiting mastery over a slave, just like his white counterparts might do—Miller had violated the social and cultural mores that governed his own local, white community. In turn, the offended members of that community chose to ignore (that is, completely misappropriate) the particulars of the statute and punished Miller for his breeching of racial protocol.

Upon receiving Miller’s petition for executive clemency, Governor Thomas E. Bramlette quickly reversed the decision and remitted the $50 fine. In the process of interpreting the law, Bramlette exposed an ironic weakness within the institution’s white supremacist foundation: the spirit of slavery in Kentucky was unquestionably based on race (white > black) and constituted a pillar of the state’s social hierarchy (white slaveholders > white non-slaveholders > any African Americans).

But to protect the integrity of the legal codes which were intended to govern the behavior of slaves and how white Kentuckians interacted with them, Bramlette was forced to concede that, according to the letter of the law, a black master (albeit a temporary one in Nathaniel Oldham) could exert the same authority and claim the same legal rights as a white master. In short, Bramlette was forced to reckon with an unanswerable question: which was a higher priority, maintaining the racial hierarchy, or maintaining the institution (slavery) that enforced the racial hierarchy? Luckily, for thousands of men and women like Ed, before Governor Bramlette left office, President Lincoln and the Union army made his decision a moot point.

Matthew C. Hulbert is an Assistant Editor of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.

SOURCES: Peter Miller to Thomas E. Bramlette, 12 Nov 1863, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky (hereafter KDLA); Commonwealth of Kentucky v. Peter Miller, Judgment, n.d., KDLA; Acts of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, Passed, Volume I (Frankfort, KY: A. G. Hodges, State Printer, 1856), 42-44.