“Cap To cap His cap Excellency cap G-o-v stop cap M super c cap G-o-f-f-i-n com graph cap Your cap Petitioner respectfully represents…”

So begins our reading as we check our transcription of the next document, a petition from a Kentucky constituent to Governor Beriah Magoffin. We do this through an oral double-proofing process, which involves one team member reading aloud the handwriting on a scan of the original document while another person compares what they are hearing to what they see on a different computer. This second computer shows the single-proofed transcription, which includes coding around dates, special characters and formatting such as underlining, page breaks, and paragraph breaks. Double proofing is one of the many steps we perform to ensure a document is correctly represented in its transcription. (See our webpages for more detailed descriptions of our document selection and editorial policy.)

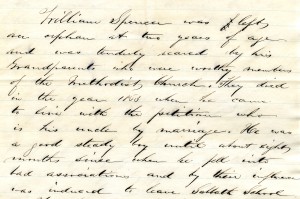

We have our own special shorthand for capital letters (cap), commas (com), paragraph (graph), superscript (super), period (stop), and so on. Among our favorites are “crash” for exclamation points, and dashes of various lengths: “monkey” for an em dash and “narwhal” for an en dash* or “hyph” for a hyphenated word. When we have difficulty deciphering a word, we attempt to rely on context, but that is not always possible. The constituents who write are often in distress and may be ignorant of the law and their rights, as well as such niceties as spelling and grammar. Our policy is to preserve misspellings, such as in the very first sentence of this post, where a constituent makes a common error in spelling Magoffin’s name as McGoffin.

Double proofing documents is a duty we approach with excitement, fear, boredom, wonder, and even compassion. It can be tedious, especially when working through the “legalese” present on many of these documents. It can strain our eyes and brains as we work to understand what the person meant by these squiggles and seemingly random marks on a page. Reading for accuracy of the letters, words, and punctuation often means we cannot focus on the content and it sometimes becomes a jumble of such phrases as “said Petitioner” and “on the date aforesaid.” Lots of “said” and “aforesaid.”

A range of emotions come over us as we read the words and digest the meaning. These documents convey the lived experience of Kentuckians during a tumultuous and confusing time. The openings are usually rather formal and standardized, but then, quickly or slowly, we are immersed in the world of the writer. Human nature is laid bare as the writers plead for help, attempt to justify their behavior, evoke pity, or make bold statements.

In this blogpost, the CWGK team shares some of our favorites in the tragi-comedy which is our double-proofing experience.

~ Deborah Thompson, Editorial Assistant ~

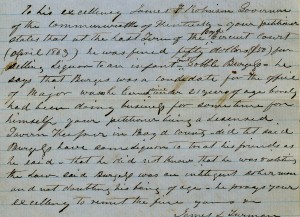

H. C. Hancock writes of a difficulty which resulted in a fight with Job Eddins in this document: H. C. Hancock to Thomas E. Bramlette. So far, pretty normal. Then comes the next part, which caused me to sit up straight: (double) “your petitioner unfortunately pulled out one of said (cap) Eddins eyes (cap) Your petitioner and the said (cap) Eddins were drunk at the time of the fight or it would not have accured (monkey)–(double)”

We thought the surprise was over (narwhal) – but wait (narwhal) – there are more twists and turns to this crazy story (crash)! Read the above document and then a follow-up document for this head-scratching tale of two friends: H. K. Dope to J. J. Gatewood .

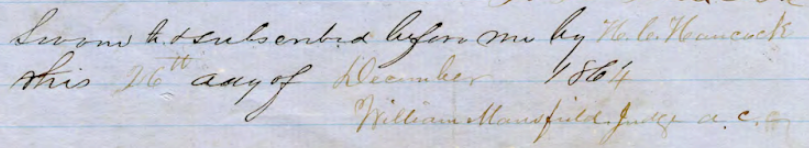

William Mansfield Judge a.c.c.

~ * ~

~ Hailey Brangers, Research Specialist ~

R. V. Wheeler of Danville was fined $25 for throwing water out of his window. In his petition, R. V. Wheeler to Thomas E. Bramlette, he insists that he was unaware of the ordinance that made this an offense. He writes to the Governor in an attempt to alleviate this fine, stating that he is “poor and illy able” to pay it. It doesn’t stop there—he actually gets sixteen men to sign in his defense over throwing water out of his window.

This document is short in length, but contains insights into both the social and legal history of Danville. Studying these petitions is an opportunity to document the histories of ordinary Kentuckians by focusing on individuals and seeing who they associated with socially, thus providing knowledge about the world they occupied. The petitions also show us societal norms or specific legal ordinances of the 1860s.

Wheeler’s petition is a perfect example of the importance of understanding the historical context of these documents, and how important it is to ask questions. By asking why a little water would be a problem —this being pre-sewer America—we may infer that he was most likely disposing of his waste or bath water, possibly creating a health problem. Danville’s ordinance was mostly likely part of the public health movement in America that began in the 1860s as a campaign against smells [1]. But again, we cannot be absolutely certain about the circumstances of Wheeler’s fine. A lot of our job requires speculating about what could be, which can be frustrating for people who need all of the answers (lucky for historians, we are quite used to speculating and asking questions!).

~ * ~

~ Charles Welsko, Project Director ~

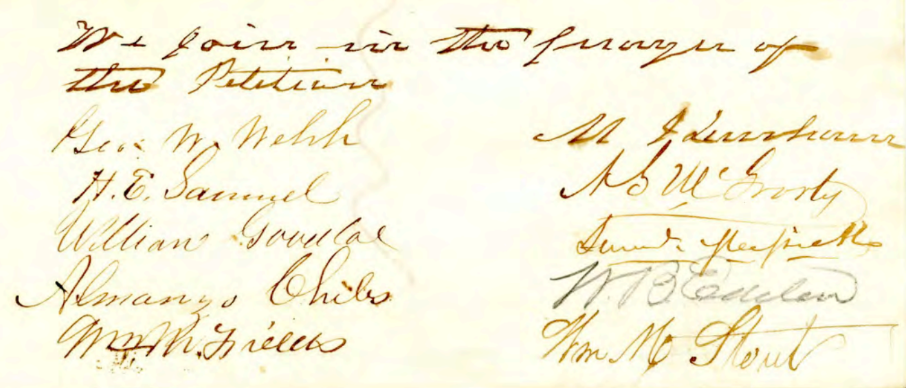

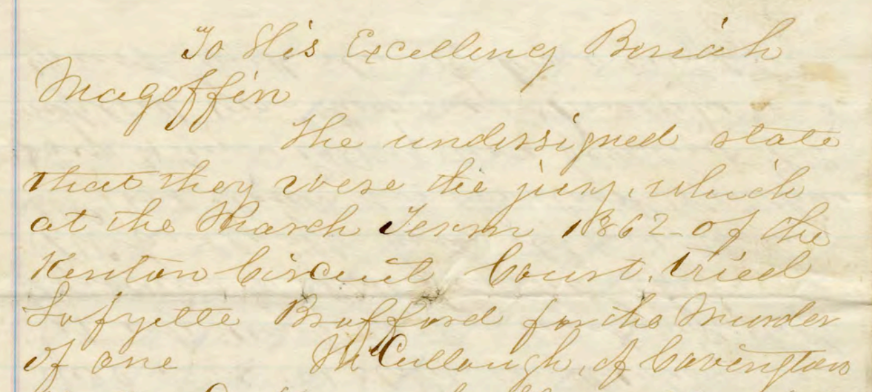

Another petition comes on behalf of Lafayette Brafford of Kenton County, from the jury that tried and convicted him, sentencing him to ten years in the State Penitentiary for killing a man named McCullough. The story is outlined in this document: Benjamin Funk et. al to Beriah Magoffin. Brafford, along with another man named Mullins (apparently remembering first names was not a skill set of the jury), were intoxicated on February 22, 1862. The petition details how Brafford and Mullins clambered into a “meat wagon” where Brafford accidentally “sat down into a bowl of sausage meat.” The drunken revelry prompted a confrontation with McCullough, the owner of the wagon, that turned from verbal argument to physical melee, where we know that Mullins produced a knife and stabbed McCullough three times in the back. Conveniently to Brafford’s case, neither he nor Mullins remembered how McCullough received the fatal stab to his bowels.

The undersigned state that they were the jury, which at the March Term 1862, of the Kenton Circuit Court, tried Lafayette Bufford for the murder of one [ ] McCullough, of Covington

This document, which provoked good laughs over the meat wagon and bowl of sausage meat, also touches on some common elements of CWGK documents. For one, there’s a continual theme of alcohol — be it the illegal sale and consumption, or irresponsible decisions derived from an excessive amount of fine spirits. More broadly, the document also represents the frequency of jurors affixing their names to petitions on behalf of individuals they convicted, suggesting that while they upheld the law, they were sometimes constrained by sentencing guidelines. They also recognized circumstances beyond their control (new evidence, pardons of other individuals, a genuine plea for mercy) that could supersede their decision.

~ * ~

~ James Bartek, Research Associate ~

Petitions for clemency or remittance of fines followed a standard format with little deviation. A petitioner stated his or her case as they saw the matter, explained why they felt they deserved clemency, and then beseeched the governor for mercy. In most instances they claimed ignorance of the law or their unintentional breaking of it. If first time offenders, they often enlisted the support of neighbors to vouch for good character. Petitions often asserted the “industriousness” of the petitioner, their economic straits, and how their family would ultimately suffer disastrous consequences of the result of the punishment of the head of household.

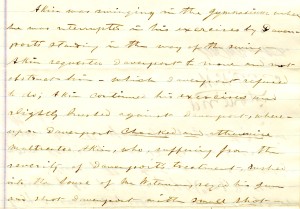

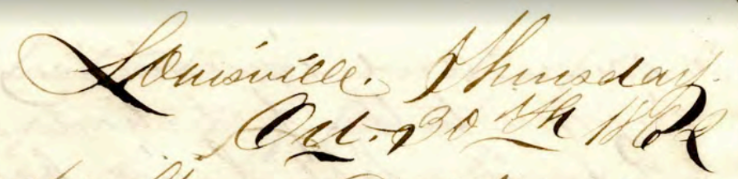

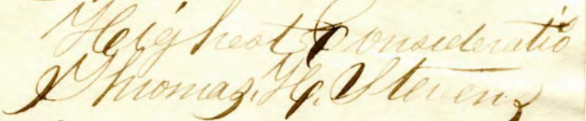

Some petitioners were more articulate than others. Such was the case of Thomas H. Stevens of Louisville, a former Union soldier convicted of first degree murder. “Your Excellency, “he began, “no one regrets the deplorable and sad casuality more than myself, and with genuine contrition of heart I pray You to absolve me from the expiration of such a severe and ignominious penalty, by restoring me to the protection and support of my family. Not being familiar with the ‘modus operand’ usually adopted in making such applications this may be defficient in many particulars, but I claim Your indulgence and hope You will make all necessary allowances for Your imperfections.”

Despite his stated ignorance of the “modus operand” of such petitions, Stevens clearly knew what he was about. “…I do most sincerely hope,” he continued, “you will not turn a deaf ear to the entreaties and importunities of an unfortunate creature who has been plunged into such a vortex of perplexing despondency, torturing suspense and humiliateing woe….”

Whether Governor Robinson ultimately granted clemency is unclear. Whatever the outcome, Stevens did much to perfect the art of the petition. View the document through this link for much more eloquence: Thomas H. Stevens to James F. Robinson.

Thomas, H. Stevens

~ * ~

~ Carl Creason, Research Specialist ~

Over the last year, I have helped double proof many documents about the sale and consumption of alcohol in Civil War Kentucky. Indeed, the volume of entries in the CWGK database involving “Spiritous Liquors” might give some researchers the impression that few Kentuckians were sober between 1861 and 1865. As you might expect, these documents often shed light on some of the most unfortunate and troubling episodes in our state’s history (acts of violence and public health concerns, to name a few). Yet they have also provided moments of entertainment during double proofing sessions by offering windows into a variety of remarkable and outlandish incidents. One such event came to us in a petition written on behalf of Charles C. Williams of Bourbon County: J. A. Prall et al. to Thomas E. Bramlette.

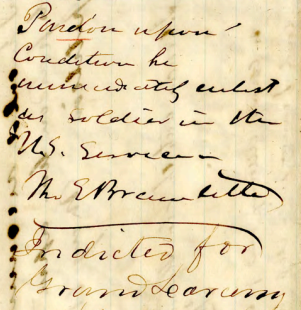

Williams, a saddler and harness maker, moved to Paris, Kentucky, during the winter of 1862-1863. The petition suggests that he began heavy drinking once he arrived in the Bluegrass state, though it provides no explanation for his change in behavior. On one occasion, “while in a frolic,” Williams “dressed himself” in another man’s clothing and took a “seat in the most public place he could find.” When questioned by officials, Williams claimed to have no memory of his actions because “his mind was crazed by intoxication.” In the end, he was indicted for “grand Larceny” and faced jail time.

So far, this story sounds similar to a number of other drunken escapades gone wrong. Someone drank too much, did something unconventional that disrupted the public order, and eventually faced the hard hand of local law enforcement. That said, a few aspects of Williams’s case stand out. First, the CWGK database contains other documents involving clothes-stealing, which often resulted in a serious penalty for the accused. Nineteenth-century Kentuckians stole a variety of things, but—as one of my colleagues suggested—people seemed to respond differently when clothes were involved. Second, the petition mentions that Williams arrived in Bourbon County as a “refugee from the South” who expressed Unionist sympathies. I tried locating him in the 1860 census but had no luck.

Indicted for Grand Larceny

Regardless, knowing that Williams was a Unionist who left a region hostile to his beliefs in the middle of a civil war, one wonders what challenges he faced before he arrived in Kentucky. Perhaps being politically ostracized from his community or arguing with family members and close friends about the legitimacy of secession explains his propensity for heavy drinking. Alone and despondent, Williams might have turned to alcohol to cope. Obviously, without additional information, these conjectures cannot be confirmed, but they call attention to the difficulties of Williams’s circumstances as a white Unionist originally from a southern state outside of the Border region who moved to Kentucky during the war.

~ * ~

At CWGK, we never really know what we’re going to see when we open up another document. The Kentuckians who corresponded with the governor may give us insight into their motives, lay bare their heart-wrenching tales, and help us understand their actions. Along the way, we may discover a unique turn of phrase, outrageous spelling, or the absurdity of the human condition. The fun part for us is being able to read over these documents and having a nice surprise each time a line catches our eyes and makes us laugh!