By Matthew C. Hulbert

Gun control—particularly when it concerns the ability of private citizens to carry concealed firearms in public—is one of the most controversial and hotly-contested political issues twenty-first-century America has to offer. Conceptions of the past often play a major role in how the debate is framed. When we imagine the United States in the mid-nineteenth century, there’s a tendency to envision everyone (minus slaves) legally carrying a weapon whenever, wherever, and perhaps most importantly, however, he or she wished. From frontiersmen (see Jeremiah Johnson [1972]) and quick-drawing shootists (see The Outlaw Josey Wales [1976]) to gamblers and their belly guns (see Maverick [1994]) or even Jim West’s spring-loaded Derringer (see The Wild West [1965-69]), pop culture has done much to reify that America was, in its “frontier days,” a gun-toting nation. What most observers don’t realize, however, is that this seemingly modern debate over the right to bear arms has actually been raging since the 1860s—and nowhere was it more intense than Civil War Kentucky.

In May 1866, John L. Peyton was indicted in the Hopkins Circuit Court for carrying “concealed deadly weapons,” which essentially meant that he’d left home with a revolver tucked under his coat or hidden in a pocket. The law in Kentucky that regulated concealed weapons dated back to March 1854:

Sec. I. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky: That if any person shall hereafter carry concealed any deadly weapons, other than an ordinary pocket knife, except as provided in the next section, he shall be fined on the first conviction not less than fifty nor more than one hundred dollars, and on any subsequent conviction not less than one hundred nor more than five hundred dollars.

Sec. II. That the carrying of concealed deadly weapons shall be legal in the following cases:

- Where the person has reasonable grounds to believe his person, or the person of some of big family, or his property, is in danger from violence or crime.

- Where sheriffs, constables, marshals, and policemen carry such weapons as are necessary to their protection in the efficient discharge of their duty.

- Where persons are required by their business or occupation to travel during the night, the carrying concealed deadly weapons during such travel.

Sec. III. This act shall be given in charge by the judges to the grand juries.

According to his supporters, Peyton had good reason not to travel in Hopkins County without a gun. In February 1866, he’d been appointed the Superintendent of Freedman’s Affairs there and charged with overseeing the transition from bondage to citizenship of the area’s African American population. Neither task nor title won Peyton many new friends among local Conservative Unionists (those who’d remained loyal to the Union for sake of protecting the institution of slavery) or among Rebel guerrilla bands (some of whom hadn’t yet called it quits in 1866).

Peyton’s defenders dispatched a petition to Governor Thomas E. Bramlette requesting that the charge be dropped. Their plea was based on two mitigating factors. First, that “being an officer of law, duly appointed, and acting and believing it to be his [Peyton’s] right and that the circumstances eminently justified it, did carrying a Colts Navy Revolver about the country for protection, during a part of his term of office.” And second, “that it would have been unsafe for said Peyton or any one else in the discharge of a similar office in said county, to have gone unarmed in the country, owing to the presence of late Guerrillas and lawless characters, who would have delighted to murder the ‘Nigger Bureau’ as he was decisively and maliciously called by them.” In other words, Peyton’s circumstances adhered to the letter of the law; carrying a concealed weapon was a de facto requirement of his job and to condemn a man in his line of work for doing so was like asking him to commit suicide.

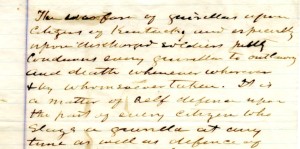

This was a problem Noah Allen faced a county away while defending himself against an identical charge in the Crittenden Circuit Court. Though not an agent of the Freedman’s Bureau, Allen was a discharged Federal soldier (formerly of the 17th Kentucky Cavalry) and, like many of his ilk, had been allowed to retain his sidearm for purposes of personal protection. Petitioners on his behalf noted that the “country was filled with desperate men, and Union soldiers were being murdered everywhere.” Worse still, while the law appeared to favor Allen’s case, the men doing the murdering seemed to control the justice system. “Our Rebel jury,” Allen’s supporters continued, “were not satisfied until he [Allen] was indicted” even though “Rebels carry their arms every where and not one have they ever been indicted.”

A few years prior to the petitions from Peyton and Allen, Bramlette had been asked to intervene in the legal proceedings against Richard Murray (1863) and Brutus J. Clay (1864). Murray, of Munfordville, Kentucky, was convicted of possessing a concealed deadly weapon and fined $100 when a revolver he was apparently hiding in his pants discharged and resulted in a serious injury. According to a petition penned on Murray’s behalf, he was unable to pay the $100 penalty for carrying the weapon because “he is now a cripple and will be for life” as a result of his self-inflicted wound.

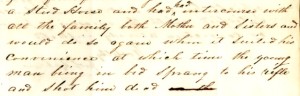

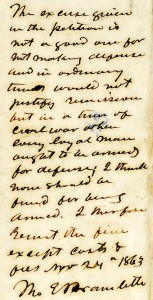

Clay, the son of noted Kentuckian Cassius M. Clay (and the namesake of Cassius’s brother, Brutus), was walking along the road one afternoon and stopped to throw a rock at a pigeon; he missed, and the stone projectile struck a bridge house. The bridge keeper, a Mr. Gale, became enraged and threatened to assault Clay—but retreated when the young man produced a revolver that had been concealed in his clothing. While their situations seem far more trivial than former Union soldiers being hunted by pro-Confederate guerrillas or a man accidentally shooting himself in the leg—and while neither seemed to meet the justifications for concealed carry as stipulated by state law—Bramlette granted each a pardon because he believed that “in a time of Civil War when every loyal man ought to be armed for defense; I think none should be fined for being armed.”

Clay, the son of noted Kentuckian Cassius M. Clay (and the namesake of Cassius’s brother, Brutus), was walking along the road one afternoon and stopped to throw a rock at a pigeon; he missed, and the stone projectile struck a bridge house. The bridge keeper, a Mr. Gale, became enraged and threatened to assault Clay—but retreated when the young man produced a revolver that had been concealed in his clothing. While their situations seem far more trivial than former Union soldiers being hunted by pro-Confederate guerrillas or a man accidentally shooting himself in the leg—and while neither seemed to meet the justifications for concealed carry as stipulated by state law—Bramlette granted each a pardon because he believed that “in a time of Civil War when every loyal man ought to be armed for defense; I think none should be fined for being armed.”

The cases of Peyton, Allen, Murray, and Clay underscored a set of deep, interconnected problems that plagued Kentucky—and its governors—during the war and its immediate aftermath. Though the state had remained loyal to the Union, many Kentuckians had only done so to protect their hold on slave labor and white supremacy. When war broke out in 1861, they couldn’t have imagined Lincoln or his Republican allies in Washington D. C. punishing their loyalty; even so, the Peculiar Institution was eradicated and, in response, violence against newly-freed African Americans and their supporters—that is, men like Peyton—exploded. (So much so that Kentucky became one of only two non-Confederate states to elicit the presence of Freedman’s Bureau agents.)

And then there were the guerrillas. Bramlette and his top commanders had struggled mightily to control them during the war and fared little better during Reconstruction, as irregular activity took on a decidedly pro-white, as opposed to anti-American hue. In turn, ex-guerrillas found more generalized support among white former Unionists. This alliance, combined with restrictive gun laws in the Commonwealth, made life exceedingly precarious for the likes of Peyton and Allen. On one hand, statutes against concealed weapons existed to protect civilians from guerrillas and outlaws—but did little to help former soldiers and current government agents when those civilians turned on them, formed terror organizations, and became guerrillas and outlaws. On the other hand, the “shenanigans” performed by Murray and Clay underscored that even in times of war, loyal men with concealed weapons could often do more harm than good—and made it difficult to justify officially loosening the reins on concealed carry during the war or afterward.

At first glance, the solution seems so obvious: to openly carry a sidearm. It was, after all, perfectly legal to do so in Kentucky during and after the war. In reality, though, there wasn’t a solution outside of carrying concealed weapons for Peyton and Allen, and both seem to have known it. To go totally unarmed meant certain harassment and potential assassination. To go armed so brazenly, however, essentially invited a fight; more to the point, it invited a fight with men who’d spent the war perfecting the art of killing and evading capture—and who had the ability to influence when and how juries enforced the 1854 statute. For lack of a better, more formal description, this scenario was simply a “lose-lose” for Peyton and Allen, a direct and unavoidable consequence of Kentucky’s unique Civil War and Reconstruction experience.

In the bigger picture, it was also a systemic problem for Thomas Bramlette and the state’s pro-Union government. Bramlette’s chief task as governor was to protect his loyal constituents—but as the nature of Kentucky’s war created a necessity for citizens to arm themselves in self-defense from guerrillas run amok on the homefront, it simultaneously created a necessity for Bramlette to more strictly enforce extant guns laws to protect certain citizens (read: Richard “the leg shooter” Murray) from themselves. It simply wasn’t possible for Bramlette to assuage both needs at once and the consequences of this inability continue to echo: the conundrum of self-protection vs. protection from self has been debated for 150 years since and shows no signs of abatement.

Matthew C. Hulbert is an Assistant Editor of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.

SOURCES: J. A. Skein to Thomas E. Bramlette, 6 Nov 1863, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky (hereafter KDLA); G. T. Wood et al. to Thomas E. Bramlette, 10 Nov 1863, KDLA; Brutus J. Clay Affidavit, 19 March 1864, KDLA; R. J. Littlepage et al. to Thomas E. Bramlette, n.d., KDLA; Richard H. Stanton, The Revised Statutes of Kentucky, Volume I (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1867), 414.