The Caroline Chronicles:

A Story of Race, Urban Slavery, and Infanticide in the Border South

“Part III – The Defense’s Case”

By Patrick A. Lewis

For those of you who missed previous installments, we’ll begin with a very brief rundown of Caroline’s story to this point. (A full accounting of the events that led to her trial for infanticide is still available here.) In 1862 Caroline Dennant, a Tennessee slave, was brought to Louisville, Kentucky, as war contraband by Don Carlos Buell’s army—she was subsequently arrested as a fugitive slave and placed in the home of Willis and Anne Levy—a few months later, Blanch, the Levy’s toddler-aged daughter died of strychnine poisoning—Caroline was soon after charged with murder, convicted, and sentenced to death. This and last week’s installments are written from the perspective of the prosecution and the defense in the matter of Caroline’s petition for executive clemency (and may or may not reflect our actual positions on her case!).

As the prosecution alleges, there is little the defense can do to refute the circumstantial evidence against Caroline. She had been held to labor as a servant and nurse in the home of the Levys. Willis Levy did acquire, distribute, and store a large amount of strychnine. After the child’s death, Caroline was seen to have facial expressions and otherwise behave in ways to which sinister motives were later assigned by witnesses. While the defense concedes this circumstantial evidence, it entirely rejects the fanciful and conspiratorial theory of the (so-called) crime advanced by the prosecution.

Yet to secure the conviction in the trial at the May 1863 term of the Jefferson Circuit Court, the defense knowingly suppressed the extent to which Willis Levy “spread enough strychnine (or poison) to kill a regiment of men” in and about his premises. Evidence freely offered by the neighbors and family of the Levy family since the time of the trial now begs reconsideration of the case. The defense appeals to the clemency of the executive for a pardon on the following grounds:

One. That having resided in Louisville less than six months before the death of the child Blanch Levy, “in a strange place without any one to advise with” except defense counsel hastily assigned her case and without adequate time to prepare, Caroline was unable to secure witnesses for her defense at the trial.

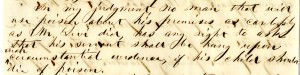

Two. That the witnesses for the prosecution, namely Anne and Willis Levy, did not testify to the full extent to which Willis Levy spread strychnine about his premises. Only two occasions were established in evidence by Willis Levy, and Caroline could swear to no more. “Your petitioner will now state one important fact which was not developed on the trial, Mr Levy put out the poison on more than two occasions; he put it out many times to kill Dogs & Cats, & it was never taken up, & what became of it no one knows.”

Three. That the testimony of Raymond and Josephine Lynch—neighbors and in-laws to the Levys, uncle and aunt of the deceased Blanch Levy—establishes the true extent of Willis Levy’s indiscriminate and dangerous application of strychnine in and around his and his neighbors’ property. Josephine Lynch swears that “Mr Levy put out the poison every night for a great while I would think a hundred times” over a span of time “from fall to spring.” Moreover, Mrs. Lynch herself had been “very uneasy many time for fear that my children would get some of the poison I alwaise thought Mr Levy was very reckless about throwing out poison.”

Four. That the prosecution argues against accidental ingestion of the poison in the yard from the fact that no pieces of poisoned meat were found in the stomach of the deceased Blanch Levy.

Five. That testimony developed on the trial and that subsequently sworn to by Josephine Lynch establishes that a considerable amount of strychnine was spread in the yard and neighbors’ yards by means other than on meat, including but not limited to on grains designed to kill birds and loosely distributed in and around the privy.

Six. That Mrs. Levy grasped the extent to which her husband had indiscriminately spread poison in and around the Levy house. Immediately after the child’s death Mrs. Levy threw out a “bucket full of parched coffee that was bought from the soldiers,” believing it to be tainted with the poison.

Seven. That if Anne Levy was made sick by coffee on the morning the child died, this was from Willis Levy unwittingly contaminating the household coffee supply with strychnine as part of his campaign to eradicate vermin.

Eight. That if the true extent to which Willis Levy indiscriminately scattered strychnine in and around his own property and that of his neighbors had been known at the time of the trial, Caroline’s conviction would not have been sought by the prosecuting attorney. Louisville City Attorney William G. Reasor attests that “from strong circumstances made known to me since that trial, I feel that Executive clemency will have been worthily bestowed if she be fully pardoned.”

Nine. That if the true extent to which Willis Levy indiscriminately and dangerously scattered strychnine in diverse methods and in diverse locations in and around his own property and that of his neighbors had been known at the time of the trial, Caroline’s conviction would not have been secured by the jury. Nine of the gentlemen of the jury who tried her case—L. A. Civill, W. O. Gardner, John Sait, Joseph Griffith, Thomas Schorch, Samuel Ingrem, R. H. Snyder, William K. Allan, and E. P. Neale—have signed a sworn statement asking to overturn the verdict and sentence they rendered.

Nine. That if the true extent to which Willis Levy indiscriminately and dangerously scattered strychnine in diverse methods and in diverse locations in and around his own property and that of his neighbors had been known at the time of the trial, Caroline’s conviction would not have been secured by the jury. Nine of the gentlemen of the jury who tried her case—L. A. Civill, W. O. Gardner, John Sait, Joseph Griffith, Thomas Schorch, Samuel Ingrem, R. H. Snyder, William K. Allan, and E. P. Neale—have signed a sworn statement asking to overturn the verdict and sentence they rendered.

All this the defense presents as evidence for Caroline’s innocence in the death of the child Blanch Levy. The defense will not—as it believes it has grounds to do—pursue the argument that Caroline’s service in the Levy household was in violation of the Confiscation Act of July 17, 1862, which provides that “all slaves of persons who shall hereafter be engaged in rebellion against the government of the United States “shall be forever free of their servitude, and not again held as slaves” and that “no slave escaping into any State, Territory, or the District of Columbia, from any other State, shall be delivered up, or in any way impeded or hindered of his liberty” regardless of the laws pertaining to enslaved persons and persons of African descent in that state, territory, or district.

The defense reiterates that given the circumstances of the defendant and her insecure position in Louisville, the evidence presented in this petition was unavailable to Caroline and her counsel at the time of the trial.

If all that were introduced in this petition were this new testimony, the defense would feel confident in their expectation of His Excellency’s clemency, but having in hand the sworn statements of the prosecuting attorney and the jury, the defense feels that the pardoning power would be justly used in the case of Caroline. The premises considered, the defense asks that His Excellency Governor Bramlette issue a full and unconditional pardon.