Sometimes when starting a new project or phase in life everything around you becomes overwhelming. I am not a Kentuckian, nor by training am I a civil war historian. However, over the course of the last three months one thing is evident as I write this post: Why do I know so little about a state, that for all intents and purposes is “Southern”? This question and my larger goals of wanting my first experience in the “real world” to be successful, led me to dive deep into my work. The Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition (CWGK) is a hidden gem in the realm of digital history. Not only has CWGK developed a unique way to examine the office of the governor, but each document is translated, annotated, and researched. The team assembled to work on this project made it possible for students, teachers, and scholars to do primary source research from their home. As part of learning about my new State (aside from the Kentucky Derby), I am taking a step back and spending my days with the Civil War Governors of Kentucky and their constituents. Which has led me to understand the internal struggle that the US faced was truly felt by all individuals, maybe more in Kentucky than others.

In July, I was brought on to the CWGK team to research and develop educational materials for all levels of scholars through an NEH Grant. I never thought that I would spend my days reading about how the tensions of the Civil War affected everyday individuals. However, that is just what happened. Over the course of the next few months, I hope you will follow along as I highlight some short narratives about the individual struggles Kentuckians faced in the war years. This week we start just prior to secession in Henderson County, Kentucky.

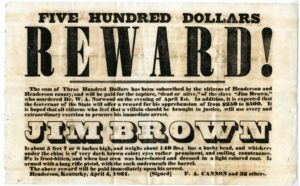

April 1, 1860, just south of Henderson, Kentucky, Dr. Walter Alves Norwood lay on the ground of his stable, dead.[1] Moments prior, a runaway slave known to those in the town as Jim Brown pulled a gun on the doctor and shot him. While members of the community wrote to Governor Beriah Magoffin requesting he take action, others took to the woods in search of the slave. The problem here, and in other places, revolved around the fact that Kentucky bordered the slave holding south and the free north. Henderson County lies along the Ohio River and Indiana— freedom. This was not the first time that Jim Brown escaped the home of his mistress Ms. Pentecost. In 1859, Brown fled the state for the freedom of Indiana for more than three months before returning to his mistress.[2] Robert Glass wrote to Governor Magoffin stating that, “It is feared that he [John Brown] has gone to Indiana (where the stepfather of his mistress lives & who harbored him for four months last year while runaway).”[3] Accounts indicate that John Brown had a wife and on multiple occasions he requested to see, but was continually denied. While Ms. Pentecost owned John Brown, Mr. Furna Cannon owned Brown’s wife. Determined to be with his wife, Brown once again ran away. Being on this border of freedom, “The [Ohio] river held both terror and hope for slaves and made slavery in Henderson County more complicated.”[4] Slaves could see their freedom, but could not have it.  After the death of Dr. Norwood, Captain Bill Quinn lead a search party, equipped with bloodhounds, into the woods and fields to flush out Brown. Their initial searches proved unsuccessful. Wanting to capture the murderer the citizens issued a reward of $500.00 for the “capture, ‘dead or alive’ of the slave ‘Jim Brown’… In addition it is expected that the Governor of the state will offer a reward for his apprehension.”[5] After a continued search of the county, John Quinn, Bunk Hart, and John H. Marshall discovered Brown hiding in the barn of William J. Marshall—John H. Marshall, “fired, the ball striking him [brown] in the right temple, causing instant death.”[6] His murderers were exonerated on the belief that they did what was best for the community. This is not an unusual story to most historians. However, the distinctiveness of Henderson County and the question of slavery, may give more insight as to why Kentucky held a unique position in the full picture of the civil war and why, it is time to reexamine how the commonwealth fits into that narrative.

After the death of Dr. Norwood, Captain Bill Quinn lead a search party, equipped with bloodhounds, into the woods and fields to flush out Brown. Their initial searches proved unsuccessful. Wanting to capture the murderer the citizens issued a reward of $500.00 for the “capture, ‘dead or alive’ of the slave ‘Jim Brown’… In addition it is expected that the Governor of the state will offer a reward for his apprehension.”[5] After a continued search of the county, John Quinn, Bunk Hart, and John H. Marshall discovered Brown hiding in the barn of William J. Marshall—John H. Marshall, “fired, the ball striking him [brown] in the right temple, causing instant death.”[6] His murderers were exonerated on the belief that they did what was best for the community. This is not an unusual story to most historians. However, the distinctiveness of Henderson County and the question of slavery, may give more insight as to why Kentucky held a unique position in the full picture of the civil war and why, it is time to reexamine how the commonwealth fits into that narrative.

I hope that you will continue this journey with me as I discover more about the individuals in Kentucky that sought advice or help from the office of the Governor, and what it meant to live in a state that allowed slavery, but aligned with the federal government in the war on slavery.

To use the story of Jim Brown and Dr. Norwood in your classroom click here.

Emily Moses is a Research Associate with the CWGK team. Her work focuses on conducting annotation research and amplifying the outreach efforts to audiences of formal and informal learners.

___________________________________________________________________

[1] Alex H. Major to Beriah Magoffin, 3 April 1861, Office of the Governor, Beriah Magoffin: Governor’s Official Correspondence File, Apprehension of Fugitives from Justice Papers, 1859-1862, MG8-114 to MG8-115, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY. Accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0001-021-0029.[2] Please note that the letter indicates that the Slave was brought back to his owner, Ms. Pentecost but it does not state if he came back on his own volition or if he was captured by bounty hunters.[3] Robert Glass to Beriah Magoffin, 4 April 1861, Office of the Governor, Beriah Magoffin: Governor’s Official Correspondence File, Apprehension of Fugitives from Justice Papers, 1859-1862, MG8-112 to MG8-113, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY. Accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0001-021-0028.[4] King, Gail, Susan Thurman, and Susan Thurman. Currents: Henderson’s River Book. Henderson, Ky.: Mail Orders to Henderson County Public Library, 1991. Held by the Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, KY.[5] F. A. Cannon et al., Five Hundred Dollars Reward!, 4 April 1861, Office of the Governor, Beriah Magoffin: Governor’s Official Correspondence File, Petitions for Pardons and Remissions, 1859-1862, MG19-518, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY. Accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0001-020-0958.[6] Starling, Edmund. History of Henderson County, Kentucky: Comprising history of county and city, precincts, education, churches, secret societies, leading enterprises, sketches and recollections, and biographies of the living and dead. Evansville, Indiana: Unigraphic Inc., 1965. P.560-561