As we continue to face the realities (and uncertainties) of the Covid-19 pandemic, we are reminded of the toll that disease took on Civil War Americans, especially soldiers who lived and operated in close quarters often without the knowledge or means to practice “good hygiene.” Over the last several weeks, we have heard numerous references to “wash your hands,” “stay at home,” “essential services only,” and—perhaps most importantly—the new phrase coined by the CDC: “social distancing.” For the majority of Civil War soldiers, these would have been foreign concepts or measures largely inconceivable during wartime (nineteenth-century armies couldn’t function with soldiers standing six feet apart). Consequently, a variety of diseases—tuberculosis, measles, smallpox, and dysentery, to name a few—spread rapidly among the enlisted population, particularly after the first year of the war.[1]

The results were disastrous. Epidemics ravaged camps and communities on both sides of the conflict. Historian Margaret Humphreys has described the Civil War as the “greatest health disaster that this country has ever experienced.”[2] Of the 750,000 deaths that occurred, disease accounted for approximately 500,000—meaning “troops . . . were more than twice as likely to be killed by deadly microorganisms as enemy fire,” explained Andrew M. Bell, author of Mosquito Soldiers.[3] However, medical professionals as well as ordinary Americans learned from the widespread outbreaks, acquiring new information about infectious diseases that helped revolutionize public health policies after 1865. Many of the modern practices employed to prevent the transmission of Covid-19 developed, in part at least, from the experiences and knowledge gained from battling epidemics during the Civil War.

Courtesy of the National Archives: “Civil War Photos”

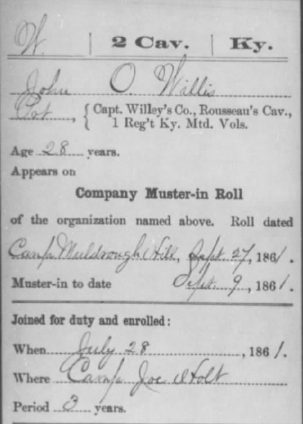

Recently, while exploring the CWGK database, I came across KYR-0001-029-0427, a petition that details the combat experiences of John O. Willis of Grayson County.[4] Reading it reminded me of the dire effects of disease on soldiers’ lives. In the summer of 1861, Willis traveled nearly eighty miles from his home in Leitchfield to Camp Joseph Holt, a federal recruiting post located across the Ohio River from Louisville in Jeffersonville, Indiana.[5] There Willis joined the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry as a private for a three-year term (though, unknown to him at the time, Willis would be out of uniform before the summer of 1863).[6]

Courtesy of Fold3 [by Ancestry]

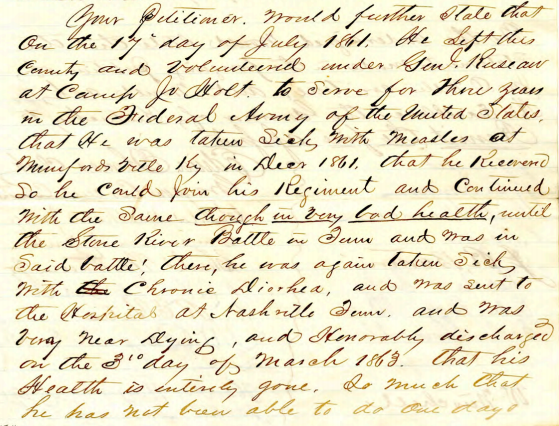

Not long after enlisting, he returned south to Munfordville in Hart County, where he and fellow members of General Lovell H. Rousseau’s 4th Brigade encamped to guard the vital railroad bridge that traversed the Green River. Willis and other Union troops busied themselves with erecting earthworks and repairing the bridge after acts of Confederate vandalism. Other than the relatively small Battle of Rowlett’s Station, which occurred on December 17, 1861, Willis avoided enemy fire.[7] Yet, over the winter of 1861-1862, he waged war against an enemy much more life-threatening to him than any Confederate foe. That December, Willis “was taken Sick” with measles, a highly contagious viral infection spread through coughing, sneezing, and close contact with infected persons.[8] Willis undoubtedly contracted the disease from a fellow soldier, and likely spread it to others in west-central Kentucky.

Willis survived the outbreak at Munfordville. By the following winter, he had rejoined his company, though he remained “in very bad health,” a complication of his bout with the measles.[9] Willis saw military action from December 31, 1862 to January 3, 1863 at the Battle of Stones River in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Casualties mounted as Union and Confederate forces engaged in fierce fighting around the small town. Of all the battles waged between 1861 and 1865, Stones River produced the highest percentage of casualties on both sides. One out of every three Union soldiers either died or incurred combat wounds.[10]

Although Willis went unscathed from battle, “he was again taken Sick”; this time, Willis contracted “Chronic Diahrea” while stationed near Murfreesboro.[11] He represented one of approximately 1.5 million cases of dysentery that devastated the Union ranks. The disease affected all levels of service—from privates to commissioned officers—because nearly everyone fell victim to poor sanitation and poor hygiene. Latrines and contaminated food spread bacteria among soldiers living in crowded quarters.[12] Modern hand-washing practices and food-safety protocols certainly would have benefited Willis and other men in uniform, but those preventative measures were absent from nearly all Civil War campgrounds, hospitals, and prisons.

Willis suffered the rest of that winter in a Nashville hospital, where he remained “very near Dying.”[13] On March 3, 1863, he was honorably discharged with a “Certificate of Disability.” Willis returned home to Grayson County where he faced charges for “Selling giving and loaning to a slave . . . Spiritous Liquors.”[14] Months before enlisting, during the winter of 1860, Willis offered a neighbor’s slave “One Dram of Whiskey.”[15] The Grayson County Circuit Court delivered a guilty verdict and issued a $20 fine. But Willis could not pay the penalty. With his “Health . . . entirely gone,” Willis wrote to Governor James F. Robinson requesting that his fine be remitted.[16] The petition included the signatures of nineteen Grayson County residents who confirmed Willis’s inability to work since returning from service; in fact, they doubted “Whether he will ever . . . Recover his health so that he can work” again.[17] As a result, on June 19, 1863, Governor Robinson issued the remission. Willis was spared the $20.

Willis lived until September 1917 (only months before the outbreak of the Spanish Flu).[18] Remarkably, he survived two epidemics during the Civil War; however, thousands of the men he enlisted with and fought against did not. Before mustering out in the summer of 1865, the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry, Willis’s regiment, lost 179 members—123 of those men died of disease.[19] Recent scholarship on the medical history of the war, particularly the work of Shauna Devine, argues that men like Willis did not suffer with (or die from) disease in vain. Rather, doctors and other medical professionals learned about contamination, developed treatments, and devised new public health policies to combat epidemics as a result of their experiences treating illnesses during the Civil War.[20] Indeed, Willis’s two years as a Union soldier attest to the importance of preventative measures to control the spread of infectious diseases—namely hand washing and self-quarantining (or social distancing). As we face our own public health crisis, we are armed with medical knowledge not available to Willis and other Civil War Americans. This information can help prevent the spread of disease in twenty-first-century Kentucky.

[1] Scholarship on the medical history of the Civil War has examined the health and treatment of soldiers from a variety of perspectives, including institutional studies of the army medical corps and U. S. Sanitary Commission, the role of women as nurses, the health of African American soldiers, the development and operation of Civil War hospitals, and disability among active soldiers and veterans. For additional reading on these subjects, consult the following works. Although not exhaustive, this list contains some of the most important publications: Frank R. Freeman, Gangrene and Glory: Medical Care during the American Civil War (Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1998); Jane E. Schultz, Women at the Front: Hospital Workers in Civil War America (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2004); Margaret Humphreys, Intensely Human: The Health of the Black Soldier in the American Civil War (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008); Andrew McIlwaine Bell, Mosquito Soldiers: Malaria, Yellow Fever, and the Course of the America Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010); Libra R. Hilde, Worth a Dozen Men: Women and Nursing in the Civil War South (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012); Jim Downs, Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012); Kathryn Shively Meier, Nature’s Civil War: Common Soldiers and the Environment in 1862 Virginia (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013); Margaret Humphreys, Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the American Civil War (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013); Brian Craig Miller, Empty Sleeves: Amputation in the Civil War South (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2015); Sarah Handley-Cousins, Bodies in Blue: Disability in the Civil War North (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2019).

[2] Humphreys, Marrow of Tragedy, 1.

[3] Bell, Mosquito Soldiers, 2.

[4] John O. Willis to James F. Robinson, 15 June 1863, Office of the Governor, James F. Robinson: Governor’s Official Correspondence File, Petitions for Pardons, Remissions, and Respites, 1862-1863, R4-184 to R4-185, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY. Accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0001-029-0427, (accessed March 29, 2020), (hereafter KYR-0001-029-0427).

[5] The 1860 census lists Willis as a twenty-seven-year-old farm laborer in Leitchfield, Grayson County, Kentucky. Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Grayson County, Leitchfield, p. 347.

[6] Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers who Served in Organizations From State of Kentucky, NARA RG 94, Microfilm Series M397, Roll 0024.

[7] Kent Masterson Brown, “Munfordville: The Campaign and Battle Along Kentucky’s Strategic Axis,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, vol.97, no. 3 (Summer 1999), 247-285; Randy Bishop, Kentucky’s Civil War Battlefields: A Guide to Their History and Preservation (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 2012), 59-73; “The Union Occupation,” Battle for the Bridge Historic Preserve (Munfordville, KY), http://www.battleforthebridge.org/Occupation.html (accessed March 29, 2020).

[8] KYR-0001-029-0427.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid; James McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, second edition(New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 582-583; James Lee McDonough, Stones River: Bloody Winter in Tennessee (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1980); Peter Cozzens, No Better Place to Die: The Battle of Stones River (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990).

[11] KYR-0001-029-0427.

[12] Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein, The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 2008), 85-87.

[13] KYR-0001-029-0427.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Vital Statistics Original Death Certificates – Microfilm (1911-1964), KDLA, Roll #7016189, Butler County Deaths, File #24346.

[19] Al Alfaro, “The Paper Trail Of the Civil War In Kentucky 1861-1865,” Notes compiled from Frederick H. Dyer’s A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (1908), https://kynghistory.ky.gov/Our-History/History-of-the-Guard/Documents/ThePaperTrailoftheCivilWarinKY18611865%202.pdf (accessed March 29, 2020), 38.

[20] Shauna Devine, Learning from the Wounded: The Civil War and the Rise of American Medical Service (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014).