By Stefanie King

Civil War Governors‘ new Early Access web interface provides researchers access to thousands of transcribed Civil War-era documents that bring new voices into conversation with historians. But how does the project move beyond the texts to provide researchers new levels of access to the lives of 1860s Kentuckians? Early Access is an important achievement for the project, more than five years in the making. Yet the next phase of work will push the boundaries of digital scholarship by using these documents to map the social network of Civil War-era Kentucky.

This summer, Civil War Governors is trying to understand how dense and interconnected a network the documents will allow us to construct. So we chose 21 documents to be our laboratory experiment before moving on to the 23,000 identified so far.

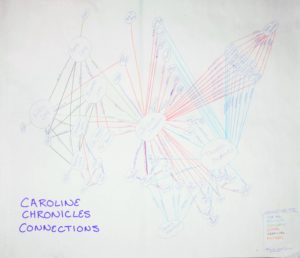

Those 21 documents contained 440 identifiable entities (IDs), including people, places, and organizations. Some of the people mentioned in the documents are easy to identify, such as the governors or other prominent members of society. Others are harder. Caroline Dennant, from The Caroline Chronicles, is is difficult to research due to the biases of the historical record, stemming from her life as an enslaved woman and then as a contraband. Most of what we know about Caroline comes from the context of the documents in which she is mentioned.

Other people are difficult to identify because of how they appear in a document—for example, the “german woman” referred to in Caroline’s court case will be tough to identify because the information about her is vague (KYR-0001-004-0131). Similarly, many of the people mentioned in the documents are difficult to identify because their full name is not included. A Kenton County petition signed by “R Mann” is a start. But is he Robert Mann or Richard Mann, both of whom lived in the county at the time? (KYR-0001-020-1405). As frustrating as it can be, though, the process of identifying little-known historical actors includes some interesting discoveries as well, such as Willis Levy’s neighbor and brother, James, who was a lightning-rod maker.

Understanding how the people are connected is a challenging task as well. One obstacle, again, stems from the limitations of the historical record. For example, we know Rev. John L. McKee met with Caroline Dennant on multiple occasions, primarily providing her with religious counsel. But were they close friends, or merely acquaintances? Without further information from the people themselves, we can only determine the nature of that relationship as revealed in the extant documents. Furthermore, the documents do not tell us why Rev. McKee decided to help Caroline. Did Caroline seek out his counsel? Did a member of Rev. McKee’s congregation request that he become involved in Caroline’s case? Did McKee and Caroline already know each other somehow? Although we know there was a relationship between Rev. McKee and Caroline Dennant, we do not know how the relationship began, or what became of that relationship.

This leads to the second step in understanding the social network in Civil War-era Kentucky, which is categorizing types of relationships. Some relationships are easy to understand: Willis and Anne Levy were married; Blanche Levy was the child of Willis and Anne Levy; Anne Levy and Josephine Lynch were sisters.

Other relationships are not as easy to categorize. For example, numerous concerned citizens petition Governor Bramlette, asking that he pardon Caroline Dennant. But what is the nature of the relationship between these petitioners and Caroline? Are the petitioners friends of Caroline? Acquaintances? Some of the petitioners, such as John G. Barret, did not even know Caroline, and Caroline may not have known all of the people who petitioned the governor on her behalf (KYR-0001-004-0129). To complicate things further, nine of the jurors involved in Caroline’s case petitioned Governor Bramlette to pardon Caroline. The jurors who convicted Caroline of murder, then petitioned that she be pardoned. What type of relationship does that indicate? “Juror” or “petitioner” may not constitute a relationship, but the action of serving on the jury or signing a petition does establish a connection between them.

Deciding how to classify a huge range of human relationships into a handful of regularized relationship types is a tricky process that balances usability and nuance, generality and specificity. If Civil War Governors gets it right, researchers will be able to discover new patterns that would otherwise not be apparent, as well as have access to a new biographical encyclopedia of everyday people of all walks of life in Kentucky history. The project will allow researchers to visualize Civil War-era Kentucky by revealing the connections that underpinned this nineteenth-century world.

Stefanie King is a Ph.D. student at the University of Kentucky and a summer 2016 intern at the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.