The Caroline Chronicles:

A Story of Race, Urban Slavery, and Infanticide in the Border South

“Part II – The Prosecution’s Case”

By Matthew C. Hulbert

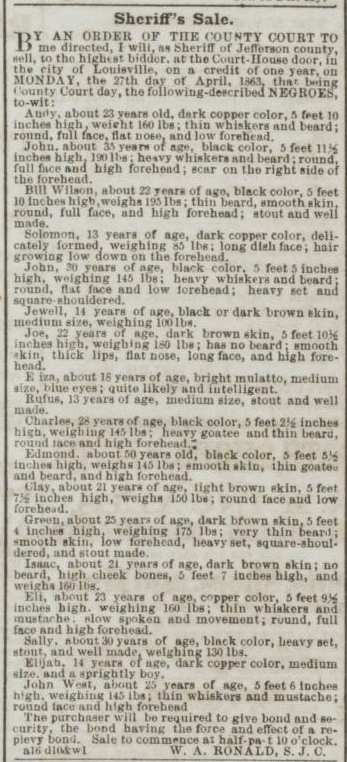

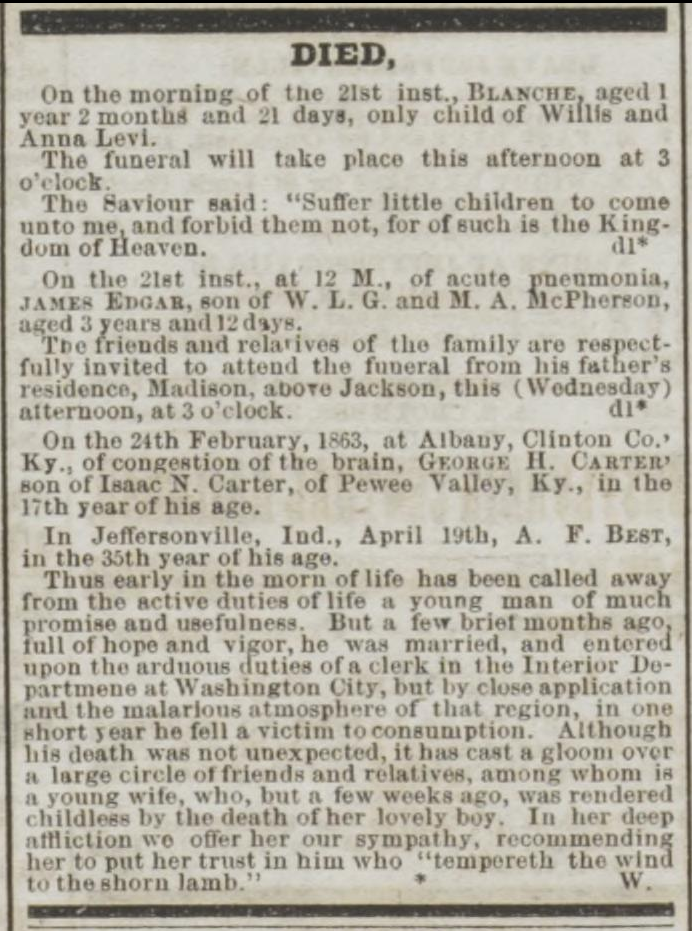

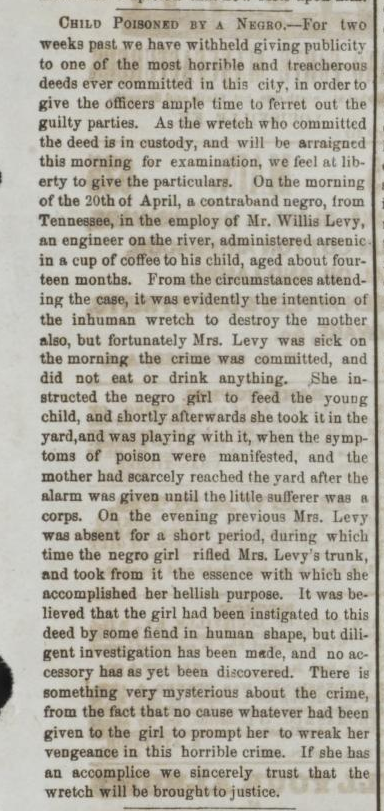

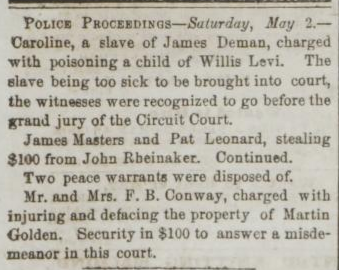

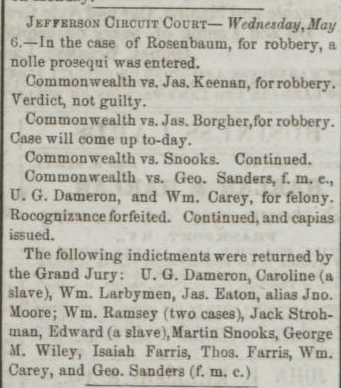

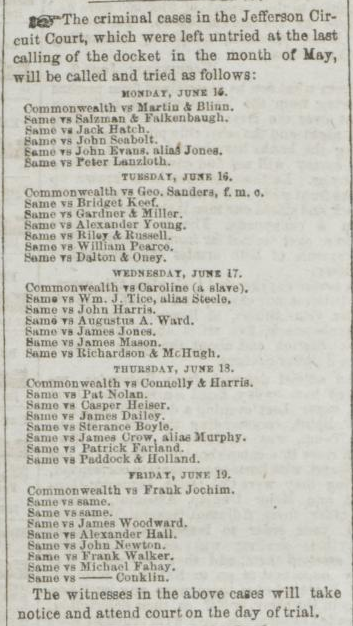

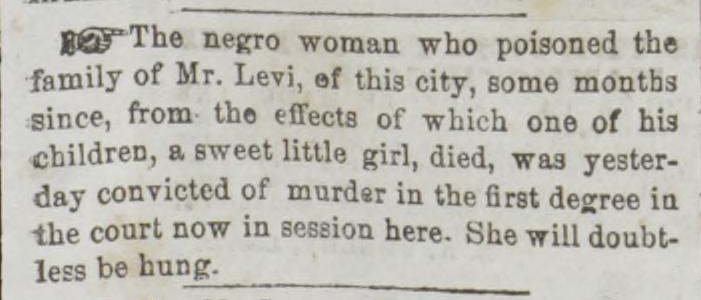

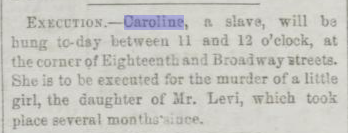

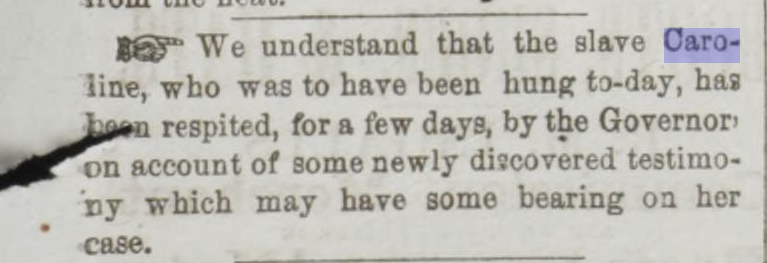

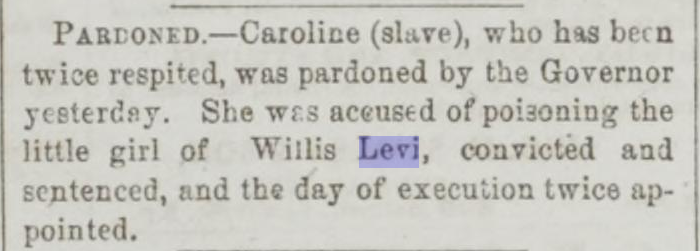

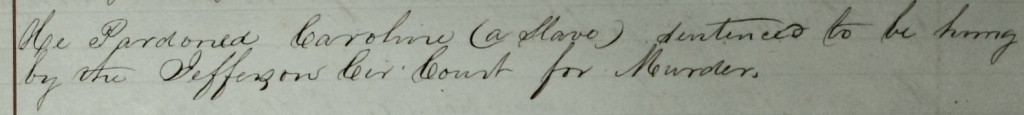

For those of you who missed last week’s installment, we’ll begin with a very brief rundown of Caroline’s story to this point. (A full accounting of the events that led to her trial for infanticide is still available here.) In 1862 Caroline Dennant, a Tennessee slave, was brought to Louisville, Kentucky, as war contraband by Don Carlos Buell’s army—she was subsequently arrested as a fugitive slave and placed in the home of Willis and Annie Levy—a few months later, Blanch, the Levy’s toddler-aged daughter died of strychnine poisoning—Caroline was soon after charged with murder, convicted, and sentenced to death. This week’s installment—and next week’s—are written from the perspective of the prosecution and the defense in the matter of Caroline’s petition for executive clemency (and may or may not reflect our actual positions on her case!).

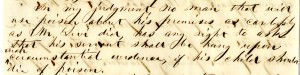

The charge against Caroline revolves around a web of evidence, the majority of which is deemed circumstantial. On the surface, this would appear to weaken the state’s case. However, in instances where such a preponderance of circumstantial evidence points to the guilt of an individual, such as in this instance, logic will not allow us to be swayed by the unreasonable possibility of coincidence. When Caroline’s case is dissected, thread by thread, you will see that she not only committed an act of premeditated murder against a defenseless and innocent child to punish her temporary guardians—but that she potentially did so as part of a broader, though admittedly poorly-conceived, plan to escape from the Levy’s care and to circumvent the possibility of a return to bondage in Tennessee.

Here are the main pillars of the state’s case, laid out as individual items:

One. We know based on the autopsy performed by Dr. Jenkins (a professional chemist) that Blanch Levy died as the result of strychnine poisoning, with significantly more than a fatal dose of the substance found in her stomach. Both the location (stomach) and quantity of the person underscore that the substance was ingested directly and not absorbed through skin contact, accidental or otherwise.

Two. We know based on her own petition for executive clemency that Caroline knew the whereabouts of the strychnine kept in the Levy household and that through the testimony of Annie Levy—that the trunk containing the poison was not locked—that Caroline had ready access to the substance whenever she pleased. The defense does not dispute either of these points.

Two. We know based on her own petition for executive clemency that Caroline knew the whereabouts of the strychnine kept in the Levy household and that through the testimony of Annie Levy—that the trunk containing the poison was not locked—that Caroline had ready access to the substance whenever she pleased. The defense does not dispute either of these points.

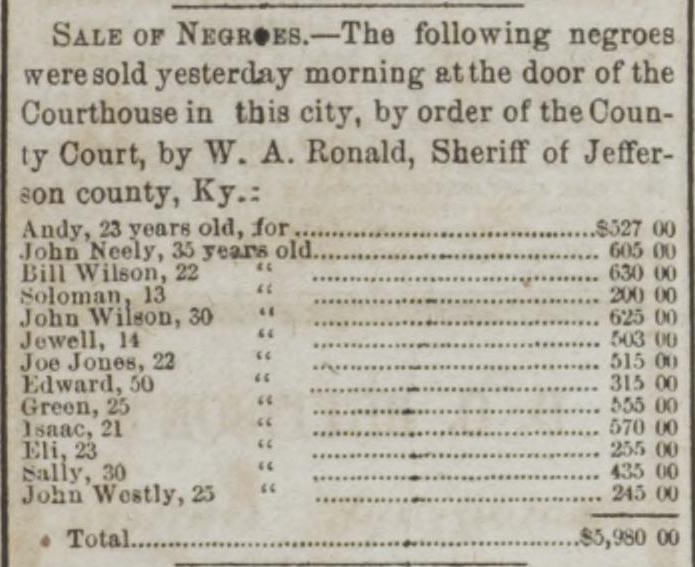

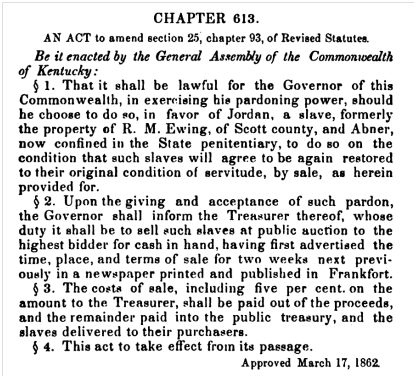

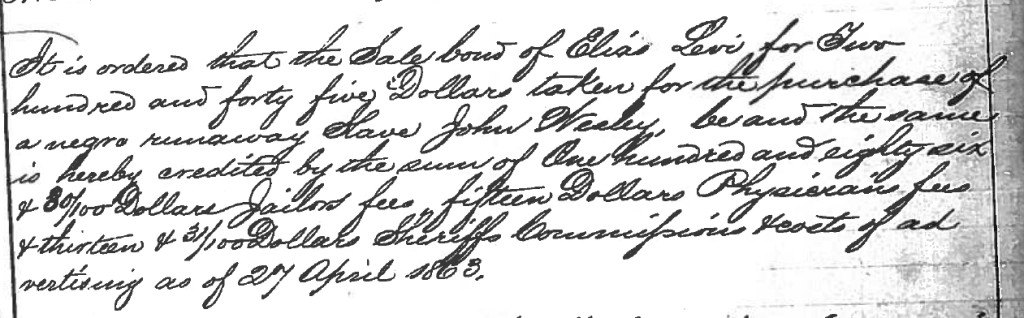

Third. Caroline had double-motive for killing Blanch Levy: revenge and personal gain. On one hand, Willis Levy became increasingly critical of Caroline’s poor behavior. The record indicates that through negligence, Caroline was responsible for damaged fruit trees and for the fouling of a newly-washed fence. On at least one occasion, the defendant reports that Willis Levy noted that he would like to whip Caroline—but the defendant did not testify to any instances of physical abuse taking place in the Levy household. Moreover, so long as she remained under the Levy’s roof, Caroline ran the risk of being returned to permanent bondage in Tennessee. As she had been declared a fugitive slave and arrested, the Levy’s were essentially providing her with a temporary home until her former master claimed her or until she could be sold at auction by local authorities.

Four. Annie Levy testified that on the day preceding the death of her daughter, she arrived home to find that the trunk containing the poison had been clearly disturbed. Caroline denied having opened the trunk, but did not deny that the trunk itself had been moved and its contents shifted.

Five. We know that in conjunction with the trunk having been disturbed, Annie Levy mysteriously fell ill with very mild symptoms indicative of strychnine poisoning—no doubt after consuming a dinner prepared by Caroline—and was still ill the next morning when she and the victim arrived late for breakfast. Caroline’s testimony does not dispute that for the first time in her entire tenure with the Levy family, she prepared and poured Annie Levy’s morning coffee. The defense does not dispute that Annie Levy noted that the coffee had an off taste and she did not finish it.

Six. We know from multiple lines of testimony that the victim, Blanch Levy, was in the sole care of Caroline in the moments preceding her death and that, for the time before she was given into Caroline’s sole care, she exhibited no signs of illness or poisoning consistent with the consumption of strychnine.

Seven. According to the testimony of Annie Levy, when Caroline entered her bedroom to state that Blanch was acting strangely (read: convulsing and choking to death in the front yard), the defendant did so slowly, without any hints of emotional distress or surprise at the events then unfolding. In connection to this lack of emotional distress, on more than one occasion, witnesses saw Caroline look at the child’s corpse and smile.

Eight. Immediately following Blanch’s death, witnesses report that, in the evening, Caroline walked to the gate of the Levy’s front yard and looked around. She had not previously been known to visit the gate in the evenings. The importance of this point will be brought to light later in the prosecution’s case.

Nine. When Caroline realized that Blanch had not been immediately interred, she became increasingly anxious concerning whether or not an autopsy would be performed, reportedly even asking Annie Levy several times when, precisely, the girl’s body would be buried.

Ten. Court documents show—and the prosecution concedes—that Willis Levy did, shortly before his departure on a freight trip, distribute small pieces of beef tainted with strychnine poison to kill local dogs and birds. However, as is also noted, Levy put this poisoned bait under the homes of his neighbors—while Caroline’s petition for clemency highlights that Blanch died just three feet from the kitchen door of the Levy’s home.

With these statements in mind, the prosecution’s theory of the crime is as follows:

While living in a constant state of paranoia—fueled by her fugitive status—Caroline quickly grew tired of working for Willis Levy and for waiting for her former master to materialize at any moment with the intention of dragging her back to bondage in Tennessee. As such, with knowledge of how to use strychnine poison and knowledge of its location in the Levy household, Caroline waited until Willis Levy had left for extended business trip and first targeted Annie Levy. Annie’s dose wasn’t fatal—though it might have been had she finished her coffee—but it was enough to induce sickness. With the child’s mother sick in bed, Caroline had sole control of Blanch. The timing of Willis Levy’s absence, the disturbance of the trunk, Annie’s sickness, the coffee incident, and Blanch’s demise in Caroline’s custody are simply too damning to write off as a coincidence. With no other adult witnesses present, Caroline fed the toddler significantly more than a fatal dose of strychnine. Following Blanch’s death, with didn’t seem to phase Caroline emotionally, she behaved with increasing strangeness; first, concerning the autopsy and burial and the child; and, second, checking the Levy’s gate in the evenings.

The defense will likely raise two primary points of defense on Caroline’s behalf. One: that she was abused and mistreated by the Levy family and killed to protect herself. However, it is well-known that the Levy family actually allowed Caroline’s husband, a contraband slave who lived with their in-laws, to spend the night with Caroline and that she, herself, did not testify to any abuse mistreatment from Levy other than harsh words. Two: that Blanch was poisoned through the negligence of her father, known in the neighborhood for poisoning animals, and that Caroline, as a homeless, African American slave, and as a defenseless woman, became Levy’s scapegoat. The logistics of the case, however, mainly the quantity of poison found in Blanch’s stomach (and the absence of the beef cubes used by Willis Levy) and the physical location of her death discounts this possibility. Furthermore, the sheer quantity of poison found in Blanch’s stomach by the attending physician means that Caroline would’ve had to watch the child ingest multiple pieces of poisoned animal bait and done nothing.

Much more likely is that Caroline waited until Willis Levy—who was more observant of her misbehavior and thus much harder to poison—had left home for an extended period of time. She then attempted poison Annie, who would presumably have died in her sleep that first evening. When that didn’t work, she again tried to poison Annie and also successfully poisoned Blanch. Caroline then checked the gate each evening because, in all probability, she was waiting for her husband to join her in an attempt to flee to permanent freedom. He never came and she was eventually found guilty following a trial in complete compliance with state and local procedures.

In closing, the state is aware that Caroline has doggedly refused to admit guilt and that a number of local citizens—including attorney’s and members of the jury—have joined her plea for executive clemency despite sentencing her to death immediately following the trial. All the state will say concerning this sudden wave of support is that Caroline’s “new friends” are more likely to be using her as a tool to advance their own political causes than to advance the cause of justice. Otherwise, where were they with aid and assistance before she was found guilty and sentenced to hang?

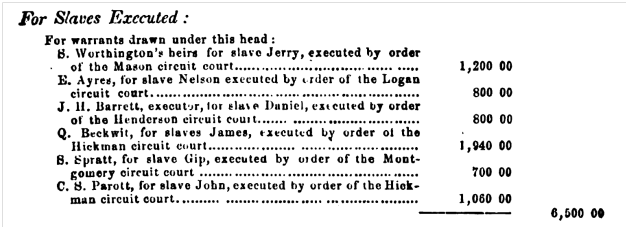

Matthew C. Hulbert is an Assistant Editor of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.