By Matthew C. Hulbert

HOMICIDE, n. The slaying of one human being by another. There are four kinds of homicide: felonious, excusable, justifiable and praiseworthy, but it makes no great difference to the person slain whether he fell by one kind or another — the classification is for advantage of the lawyers.

– Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary

“Where you find the word Guerrilla, may be understood murder, rape, arson, or robbery…”

– Major Gen. John M. Palmer, U.S.A.

By winter 1864, Kentucky’s homefront was drowning in irregular violence. Pro-Confederate guerrillas like Jerome Clark (alias Sue Mundy), Henry Magruder, Bill Marion, Samuel “One-Armed” Berry, Jim Davis, Hercules Walker, and untold others terrorized Unionists throughout the state. In turn, Unionist bushwhackers and guerrilla hunters—men such as Edwin “Bad Ed” Terrell and his band of “Independent Kentucky Scouts”—wrought their own brand of havoc on suspected Rebel sympathizers. Raiding, murder, retaliatory assassinations, and arson quickly became commonplace as Union authorities struggled, and largely failed, to find a solution. Such was the perilous environment into which two brothers from Taylor County ventured one December morning in search of a stolen mule. This unfortunate duo, Merritt and Vardiman Dicken, wouldn’t survive the day.

The Dickens first stopped at the farm of a known horse thief named Rinehart; he wasn’t home, but while the brothers conversed with his wife, two strangers appeared on horseback. The unnamed men volunteered to help Merritt and Vardiman find Rinehart, and possibly their lost animal with him. Not long after departing, however, “the two Dicken brothers, having become suspicious of the intentions of their two guides, refused at this point to go with them any further.” The situation quickly turned violent.

They [the strangers] quickly turned upon the two Dickens, took from them their pistols—shot one of them (Merritt Dicken) through the body, and the other turning to flee was also mortally wounded through the back. Merritt Dicken also turned to run, and he and his brother made all speed in the direction of a point on the extension of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad where some Irishmen were at work, about ¾ of a mile from where they were shot.

At the rail junction, things did not improve for Merritt and Vardiman. Because they approached “in a wild and excited manner on horseback at full speed” and both wore calico shirts with pistol belts, the rail men mistook the pair for guerrillas. And despite their story—and vows of Unionism—Michael Foley, a former private in the 9th Kentucky Cavalry, took it upon himself to arrest the Dicken brothers. They again fled for help, this time to the home of Charles Prewitt, where Foley caught up. With Vardiman resting inside the Prewitt house, Merritt twice refused to turn himself over to Foley peacefully, “whereupon Foley shot and killed him.” (Vardiman succumbed to his wounds a few days later, but not before relating the Dickens’ entire story to at least one witness.)

Foley was promptly arrested, charged with the murder of Merritt Dicken, and held on $5000 bail by Judge R. A. Burton of the Marion County Court. Before the trial had even concluded, area Unionists took to Foley’s defense; they argued that the circumstances of the case warranted full executive clemency from the governor, and told him as much in an official petition. After all, they claimed, the Dicken brothers had looked very much like guerrillas—heavily armed and thundering down on the rail junction at full gallop—and Foley only did “what he conceived to be his duty as a good citizen” to protect the community from marauders. Better still, the petitioners contended that the circumstances of the shooting, combined with “the impulsive nature [sic] characteristics of his race” should render Foley automatically innocent by reason of inferior genetics. In other words, who could really blame a stereotypically hotheaded Irishman for killing a guerrilla look-alike in a region infested with real guerrillas?

Even with such “creative” defenses, Foley’s prospects with the jury looked bleak. That is, until Governor Thomas Bramlette granted him a full pardon without even waiting to hear the jury’s decision. Perhaps even more remarkable than the act itself was the logic behind it:

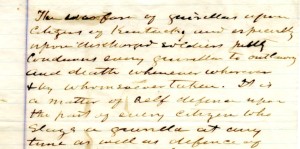

The warfare of guirillas upon citizens of Kentucky and especially upon discharged soldiers justly condemns every guerrilla to outlawry and death whenever wherever & by whomsoever taken. It is a matter of self defence upon the part of every citizen who slays a guerilla at any time as well as defence of society … the facts in this case could not have justified any other belief in the mind of Foley … no man who kills a guerilla should suffer it I can prevent it and when an honest mistake like the present is superinduced by the imprudent conduct of the slain Executive Clemency is equally deserving.

Two points concerning Kentucky’s guerrilla war emerge from the Dickens’ story and Bramlette’s pardoning of Foley, the first explicit, the second inferred.

1. Irregular violence had become such a hopeless quandary by December 1864 that for Union authorities, it was safer to kill any potential guerrilla—at the risk of murdering innocent civilians like Merritt Dicken—than to chance any actual guerrillas escaping a just execution. (A little more than a week later, Governor Bramlette would issue a proclamation calling on Military Commandants to take “the most prominent and active rebel sympathizers” as hostages “in every instance where a loyal citizen is taken off by bands of guerrillas.” The “Summer of Burbridge” that followed was a disastrous misstep for anti-guerrilla operations.)

2. Though it probably didn’t dawn on Bramlette when he issued the pardon, in doing so, he effectively conceded that irregular violence had become so problematic as to necessitate still more irregular violence—in the form of vigilantism—to combat it. A vicious cycle, indeed.

Spelling troubles aside, Governor Thomas E. Bramlette had very strong thoughts on Kentucky’s “guirillas” – see them in this excerpt from Foley’s pardon.

In this light, it really isn’t a stretch to say that the inability of Bramlette and the Union military to stamp out guerrilla activity simultaneously killed the Dicken brothers and justified freedom for one of their killers. Ambrose Bierce would have appreciated this irony on behalf of the murdered Merritt Dicken—especially considering Thomas Bramlette’s profession before ascending to the governorship: judge.

Matthew C. Hulbert is an Assistant Editor of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.

SOURCES: J. M. Fiddler and F. B. Merrimec to Thomas E. Bramlette, 18 Dec 1864, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky (hereafter cited as KDLA); Hill and Knott to Thomas E. Bramlette, 16 Dec 1864, KDLA; Proclamation by Governor Thomas E. Bramlette, 4 Jan 1864, KDLA; John M. Palmer to Thomas E. Bramlette, 18 Oct 1865, KDLA.