Click here to view this Subject Guide in the new Civil War Governors interface.

On June 14, 1864, John T. Smith penned a letter to Kentucky governor Thomas E. Bramlette. According to Smith, the County Court of Logan County had selected him to serve as a special messenger. His task: hashing out a solution for Logan County’s guerrilla infestation. “Our object,” Smith wrote, “is to fall upon some plan so as to have a company to act against Guerillas … the condition of most of us is such that we can not be spared long at a time from our families and therefore can not with propriety volunteer regularly and devote our whole time to the Service but we can raise a sufficient number to keep off guerillas and robbers by taking turn about with each others.”

Stationing troops in the area—an oft-used solution for localized outbreaks of irregular violence in Kentucky—wouldn’t do in this case; outside soldiers, the Logan County contingent argued, “are unacquainted with the country and its citizens and can do but little in catching guerillas who are well acquainted with both people and country.” Put another way, guerrillas had home field advantage against regular troops and it would take an insider to catch an insider. Smith and his comrades were willing to use their own intimate knowledge of Logan County to hunt pro-Confederate bushwhackers (on a part-time basis), so long as Governor Bramlette would provide them with supplies, firearms, and the state’s permission to wield them with lethal force.

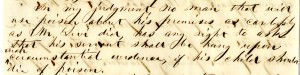

Perhaps most interesting, though, is the postscript of Smith’s letter. It reads as follows:

P.S. We are troubled by all sorts of Guerillas. Since writing the above, I learn that a squad of federal guerillas or negro Soldiers from Clarksville Tenn. came into the neighborhood of Voleny last night (the place visited by rebel guerillas two nights before) and stripped the citizens of their negroes and horses. It is a perfect outrage upon our country. The Federal Soldiers at Clarksville are so busy recruiting negroes that they pay no more attention to guerillas and robbers than if they belonged to the same class of individuals. If we are permitted to raise our company give us instruction what is to be done with negro guerillas. I think we can raise from 150 to 200 men a portion of whom can always be in motion and when necessary all can act.

Aside from Smith’s views on black enlistment, this addendum reveals the extent to which Logan County residents were caught between a gray rock and a blue hard place: pro-Confederate guerrillas would raid a neighborhood and take what food and horseflesh they needed to operate in the bush. Then a group of Unionist guerrillas—sometimes even black Unionist guerrillas—would come through the same neighborhood, accusing the residents of having willingly supplied the Confederates. This cycle could repeat itself ad infinitum (and often in the reverse order), with local citizens trapped in the middle. And it was anything but limited to Logan County — this was a state-wide problem.

So if you’re interested in finding out how Governor Bramlette, private citizens like John Smith, and/or Kentucky’s military forces waged war against irregular combatants, check out this subject guide on Guerrilla Warfare — but be advised that it only represents the tip of the iceberg.

***

SUBJECT GUIDE: Guerrilla Warfare

KYR-0001-001-0008 – Thomas E. Bramlette, Proclamation by the Governor, Jan. 4, 1864

It is in the power of persons whose sympathies are with the rebellion to prevent guerrilla raids, almost invariably, by furnishing to Military Officers of the United States or State of Kentucky, the information which experience has proved them to be, as a general thing, possessed of.

If all would unite, as is their duty, in putting down guerrillas, we should soon cease to be troubled with their raids. A neglect to afford all assistance and information which may aid in defeating the designs of marauding parties, can but be construed as a culpable and active assistance to our enemies.

I, therefore, request that the various Military Commandants in the State of Kentucky will, in every instance where a loyal citizen is taken off by bands of guerrillas, immediately arrest at least five of the most prominent and active rebel sympathizers in the vicinity of such outrage for every loyal man taken by guerrillas. These sympathizers should be held as hostages for the safe and speedy return of the loyal citizens. Where there are disloyal relatives of guerrillas, they should be the chief sufferers. Let them learn that if they refuse to exert themselves actively for the assistance and protection of the loyal, they must expect to reap the just fruits of their complicity with the enemies of our State and people.

KYR-0001-002-0018 – Berry S. Young et al. to Thomas E. Bramlette, Feb. 16, 1864

The Undersigned citizens of Crittenden having been informed that by Legislative enactment and by the authority vested in you as Governor of said State that forces are to be Raised for the defense of the state against Guerrilla invasion if such be the fact We would Recommend to your favorable Consideration Lieut F S Loyd of Co H 20th Ky Regt as Col and J N Hughey 1st Sergt Co E 48th Ills Regt ^for Lt Col^ both Recruited from this (Crittenden) County both of them accomplished Gentlemen and Soldiers they Refer you to Col Edward of your Staff By promoting those Young Gentlemen you will greatly oblige the Undersigned and Reward merit gained by gallant service in their countrys cause

Berry S Young clk c c c

James M Steele

W C Carnahan

S L. R. Wilson

Robt F Haynes County Atty,,

J H Walker Clerk

Crittenden Circuit Court

D N Stinson Post Master at Marion Crittenden Co Ky

John N Woods

Alfred Armstrong

James W Wilson —

- E. Black

J C Henson

- L. Leigh

S U Elder

KYR-0001-004-0996 – George Shirley and E. Wilty, Affidavit, Jun. 13, 1864

State that John Branstetter an infirm old man of near 70- years has lived many years in this county (formerly Barren County) a respected & good citizen and up to the commencement of this Rebellion a Sober & discreet man- that the Guerrilas Robbed him of a great deal of his property. From the troubles consequent there to & the additional fact we suppose, that his two sons Joined an independent company called the “Metcalfe Tigers” for the purpose of hunting down guerrillas & were exposed to many dangers the Old man took to drink- While in one of his drinking sprees he was induced by some bad men to go into the woods & play a game of cards. The game was played on his land & money was bet & won as appears by the evidence Testimony of a credible witness- who chanced to come upon them & saw the game He has been indicted therefore tried & fined $200- which is the least the law provides in such cases This old man is often delirious & wild wherein these drinking sprees & has to be guarded sometimes We his neighbors & friends are candid in representing that we think this is one of the few cases which demand the interposition of the Governor and ask that his fine be remitted.

KYR-0001-004-1941 – Z. Wheats to Thomas E. Bramlette, Jun. 19, 1865

I called at your office to-day & left for your consideration, the Petition of Capt. Edwin Terrell of the Independent Ky Scouts. I hope you will grant the prayer of his petition. He is one of the bravest men I ever saw, & has done more to rid Kentucky of Guerrillas than any man I have heard of. The fact is, his little band have been more effective in this service, than some Brigades of Cavalry. His head quarters were in Shelbyville & they gave our town & county protection which we could not have obtained from any other source.

KYR-0001-004-1380 – Hill and Knott to Thomas E. Bramlette, Dec. 16, 1864

Sir: As you are doubtless aware this portion of our State has long been infested by a gang of Guerrillas whose depredations have been committed almost with impunity, in Spite of the utmost vigilence of the Military, whose efforts to capture or destroy them, they have constantly managed to elude. So frequent and successful have been their forays—characterized by murder robbery and plunder—that their presence has become a cause of extreme terror to the citizens of whatever portion of our community they may mark as their prey. Some three weeks ago they made a raid through a portion of this County murdering some, robbing others, and maltreating in some manner, nearly all with whom they met.

KYR-0002-225-0083 – M. E. Poynter to Thomas E. Bramlette, Feb. 15, 1865

I trouble you with a line in regard to the recruiting officer for the State Service at this place who professes to have authority— from you to raise a company &c. I refer to W. W. Harper— and as a citizen and a Union man in behalf of the cause—the community, your own good name and of common decency I protest against such an appointment—As badly as this service demands men and as much as we have suffered from guerrillas we as a community had rather Quantrell, would pay an occasional visit than be annoyed by this man in “brief authority”— all the time.

KYR-0001-003-0086 – E. H. Hobson to Thomas E. Bramlette, Mar. 5, 1864

The 37th Ky Mounted Inft has greatly improved, Since Col C J Hann took command this Regt has recd its Horse equipments and enfield rifles but to make them more efficient would most respectfully Suggest that you arm two or four compns of the regt with Ballard Carbines or muskatoons I am anxious to have the Regt mounted and send them to the Cumberland to protect the Border Counties. the notorious Gurilla Capt Richardson and nine of his men will arrive here to day as Prisoners, they Justly merit and I hope will be punished with death give Col Hansons wishes your favourable consideration.

KYR-0002-022-0062 – W. M. Allen to Thomas E. Bramlette, Dec. 23, 1864

The last raid resulted in the death of two of our best citizens, and the killing of three of the band, and the wounding of three others of them. It was at first supposed that two of them killed at Jeffersontown were Federal soldiers, taken prisoners by the gurillas but we are all satisfied that they were deserters & gurillas. Our people are now pretty thoroughly aroused, and are anxious to have them pursued and exterminated. When pursued, these cut throats flee to the Salt River hills and scatter about among their friends and cant be found. We know who many of their aiders and abettors are but have no power to punish. The Military Authorities give us but little protection. We want something of our own that will be more efficient. It is proposed by some to raise 100 men in our county at our own expense!

KYR-0002-225-0079 – John F. Lay to Thomas E. Bramlette, Mar. 11, 1865

I have the Honor to make aplication to you for authority to recruit a Company of State troops to Serve in the State of Ky for the period of twelve months I have Served over three years in the Fedral army and know Cannot remain at Home on account of Gurillas if you will favor me with authority please Send me Some Blank Enlistment papers

KYR-0002-225-0037 – W. H. H. Faris to Thomas E. Bramlette, Apr. 24, 1864

I have presumed to address your excellency on a matter of some importance. It is the method we should adopt as the most proper for the defence of our state. The two already provided, the state troops and militia, have not proved sufficiently available. It is as much as the state troops can do, to guard the frontier, so, as to prevent the greater inroads of bodies of five hundred men. And sometimes a thousand. While parties of from thirty to forty can slip in between the posts that establishes the military chain along the southern border, effect every species of robbery, and commit any depredations they wish, and pass out again with perfect impunity. This predatory warfare is to be made on Kentucky during the three seasons when the woods are thicker, so they (the guerrillas) can practice it with greater security. This mode of warfare is characterized by the guerilla chieftains as the scouting systems. All this the militia are intended to prevent, but in which they will most signally fail; as they have done as they have done already.

Because there is ^no^ method, no arrangement no anything about them that is calculated to intercept, or overtake one of those flying bands of guerillas that pass through one county, and into another (committing all the mischief they wish) before the one has been, or the other is aware of its approach.

KYR-0001-019-0156 – Bennett Spearger to D. E. Downing, Aug. 14, 1862

The guerrilla warfare is working its ruin as a cause produces its effect a few yesterday about 2. oclock. P.M. there were 2 Union Men Killed on the Road leading from my house to Thompson Arterberry’s Hamilton and a bout 30 other men came into Tompkinsville yesterday morning a bout 8. oclk a.m. and had Nathaniel Austin and ^a^ young Hefflin Prisenors they shot Austin through the head and lefthis Brains was scatered in the road and they shot Heflin in several places, you are acquaintd ^with^ Austin and Heflin Both neither of them you Know never belong to any army the man who stealthily takes deliborate aim at the husband and Father of a helpless family ^and^ because he is freind to his Country, sends the mesenger of death to drink his life blood and compells the heart stricken widow and helpless Orphans to seek protection and support at the hands of a cold unfeeling world. Could the hands of a cold grave’s dread monster enter claim to such a fiend in any form too horrid to mete out to them there just deserts

SOURCE: John T. Smith to Thomas E. Bramlette, 14 June 1864, Kentucky Department of Military Affairs (KDMA).

It’s always nice when CWGK documents walk right into our office! While going through old family papers, KHS Head of Reference Services Cheri Daniels found an 1865 land grant to one of her ancestors, Matthew Pace, signed by Governor Thomas E. Bramlette. Land grants such as these are particularly difficult for CWGK to track down because they move administratively from the County Courts briefly to the executive department in Frankfort, and then back into the hands of the grantee. Documents like this one, in short, will likely have to come to CWGK via family holdings like Cheri’s.

It’s always nice when CWGK documents walk right into our office! While going through old family papers, KHS Head of Reference Services Cheri Daniels found an 1865 land grant to one of her ancestors, Matthew Pace, signed by Governor Thomas E. Bramlette. Land grants such as these are particularly difficult for CWGK to track down because they move administratively from the County Courts briefly to the executive department in Frankfort, and then back into the hands of the grantee. Documents like this one, in short, will likely have to come to CWGK via family holdings like Cheri’s. Will this document change the way we understand the Civil War era in Eastern Kentucky? Perhaps not. But it does underscore the importance of every document in the CWGK corpus. Each document contains a link to the lives and stories of everyday people from across the Commonwealth and the globe. And bringing these documents together in digital public space allows CWGK researchers to make connections between one another in the context of our shared past.

Will this document change the way we understand the Civil War era in Eastern Kentucky? Perhaps not. But it does underscore the importance of every document in the CWGK corpus. Each document contains a link to the lives and stories of everyday people from across the Commonwealth and the globe. And bringing these documents together in digital public space allows CWGK researchers to make connections between one another in the context of our shared past.