Last week, Matt Hulbert explored the contradictions between the Jeffersonian, states’ rights rhetoric of the provisional Confederate government of Kentucky and its actual record of heavy-handed governance and suppression of civil liberties in the counties under its control in the winter of 1861-62. In his piece, we learned that provisional Confederate Governor George W. Johnson accused the Union party in Kentucky of polluting Kentucky’s declared neutrality (which lasted from May through September, 1861) from the outset, always intending to use neutrality to save the state from secession and deliver it to the Union cause. And they did. The problem was, Matt tells us, that the Confederates had precisely the same game plan going into the summer of 1861, but were politically outmaneuvered and, later, outvoted. The rebels lost the neutrality cold war and convened their rump secession convention when they lost their bid for the legitimate government in Frankfort.

I want to jump back to that cold war, to show just how the rebels used the cover of neutrality to prepare the state for secession and civil war. In the weeks after Fort Sumter, Magoffin rejected Lincoln’s request for troops and called a special session of the legislature to consider considering secession. As Magoffin’s famous exchange with Alabama Secession Commissioner Stephen F. Hale reveals, the governor was a conditional unionist, not an outright secessionist. Lincoln’s call for troops, though, proved the limit of Magoffin’s conditionalism, and like many Upper South politicians after Sumter, he seems to have been in favor of secession. To his credit, though, Magoffin genuinely respected the will of the electorate and knew that if Kentucky were not to devolve into a miniature civil war, it must secede legitimately – through a convention called by the legislature or direct legislative action. The closest he (and all the Kentucky secessionists) could get in the May 1861 special session was neutrality and the hope that the political winds would blow the majority of Kentuckians to their side as the year wore on.

With the special session yet to convene in Frankfort, Magoffin began to set the state’s military house in order for whatever decision – secession, Union, or neutrality – might result. As chief executive and commander in chief, Magofffin could take out loans and expend state funds for arms and ammunition that (theoretically) would be put to any purpose the people of Kentucky demanded. By working through fellow secessionists at home and across the Gulf South, though, Magoffin could covertly ensure that if the cold war between unionists and secessionists turned hot, his party would have the upper hand.

Magoffin tapped Luke Blackburn to coordinate buying the weapons. Blackburn, a postwar governor of Kentucky, is most famous for his unsuccessful 1864 plot to blight northern cities with yellow fever with infected blankets from Bermuda routed through Canada. Yet secret missions involving Britain, the Caribbean, and the Gulf South had been Blackburn’s forte since the very outset of the war.

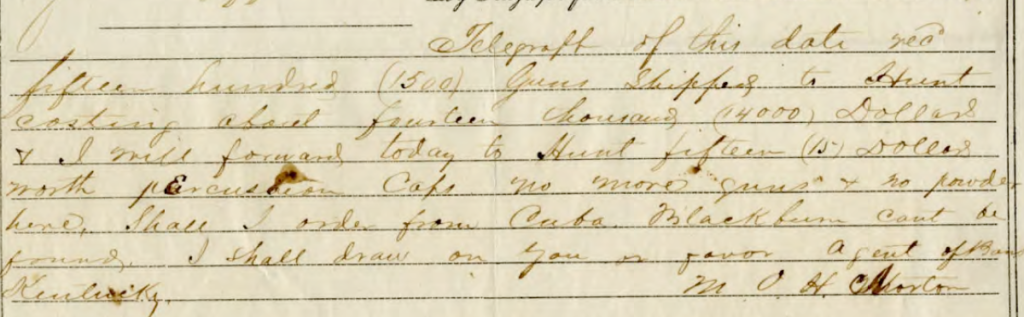

Things began promisingly. On April 26, Blackburn wired that he had “purchased two pieces heavy Ordnance two thousand muskets six hundred Kegs powder” and asked for $30,000 to be transferred from a Kentucky bank to his credit. Blackburn’s preferred shipping company, commission merchants Hewitt, Norton, & Co., whose antebellum business had brokered southern cotton between New Orleans and Liverpool, put 1,500 guns costing approximately $14,000 on rail cars bound for Louisville on May 1, but warned that the frenzied buying from agents of other southern states meant that other supplies were drying up quickly. The firm had only secured $15 worth of percussion caps and could find no more powder. “Shall I order from Cuba”? asked Louisiana Secession Convention member M. O. H. Norton. “Blackburn cant be found.”

KYR-0001-019-0023

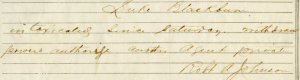

No one knew where Luke Blackburn had gone, and no one could act on Magoffin’s behalf as the available supplies in the Gulf South dwindled. When Norton requested new instructions on May 2, Magoffin was more than happy to turn the operation over from Blackburn to Norton, with additional funding secured by Louisville pork merchant Benjamin J. Adams. Fellow Kentuckian and cotton broker in the Louisville-New Orleans firm of William T. Bartley & Co. Robert A. Johnson had notified Magoffin the day before in a private cable that “Luke Blackburn [was] intoxicated Since Saturday” and urged the Governor to “Withdraw powers authorize another Agent”.

KYR-0001-019-0029

Luke Blackburn was certainly neither the first nor the last Kentuckian to let the French Quarter get the better of him. But why had Magoffin trusted him for the mission?

Though a Kentucky native, Blackburn was living and practicing medicine in New Orleans in 1861. In fact, he had lived his adult life in the cotton kingdom along the banks of the Mississippi River. Blackburn had lived in Natchez, Mississippi, as a young man and had family ties to Helena, Arkansas, where his interests and kin overlapped with “The Family,” an early Arkansas Democratic political dynasty built on Kentucky connections to provisional Confederate Governor George W. Johnson. Taken alongside Blackburn’s later experiments in biological warfare, the New Orleans arms deal raises important questions about how elite antebellum Kentuckians participated in a complex – yet surprisingly intimate and personal – international economy of slaves, cotton, liquid capital, and thoroughbred horses and how those economic connections encouraged them to address the question of secession. These kinship-political-business relationships are precisely the sorts of interconnections that the future social networking capability of CWG-K is designed to document.

Little wonder, then, that when Magoffin needed arms for Kentucky, he tapped into the networks that funneled cotton, slaves, and capital up and down the river from Kentucky to New Orleans and out to the world. Magoffin’s fallback agents at Hewitt, Norton, & Co. fit precisely the same profile. Kentucky’s 1861 neutrality was not an inward facing, isolationist political posture. The way Magoffin managed arms procurement demonstrates that he understood the Civil War as a conflict over global agricultural and industrial markets, a war fought for the interests of the southern states in and on an international stage.

Patrick A. Lewis is project director of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.