“William Brockman says that at the present term of the Jefferson Circuit Court he was tried on an Indictment for the murder of one Adolph Logel”

Two German immigrants got into a deadly fight over a pile of animal carcasses in the suburbs of Louisville. Read the full transcription of Brockman’s pardon petition here, or browse the highlights to see why this is one of the most fascinating documents in the Civil War Governors of Kentucky collection.

“[Brockman] lives in the suburbs of Louisville not far from the old Oakland Race Course at which point the general government Keeps stabled a large number of horses and mules &c the chief part of which have been worn out in the military service of the government”

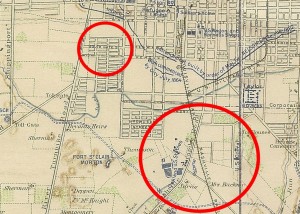

Though Oakland, one of thoroughbred racing’s popular early venues, had ceased to hold meets by the beginning of the war, its old stable facilities were perfect for the U.S. Army’s program to refit broken down cavalry, artillery, and draft animals. As the map of the southern suburbs of Louisville shows, the course sat astride the Louisville & Nashville Railroad line, affording military transport trains easy access to the large complex of stables and corrals around the old track.

“considerable numbers of these animals die daily and the persons having them in charge were in the habit of hauling them to a strip of woods near petitioner’s House and there leaving them to rot”

Using the 1860 census and city directories, we can determine that Brockman lived in the circled suburb near South Gate Street, just barely inside the expanded Louisville city limits. The carcass pile (understandably not marked on the map) was nearby, perhaps in the lot behind Fort St. Clair Morton or the stretch where the military road runs next to the creek near the Salt River Turnpike.

“Your Petitioner had obtained leave to take the skins off of these carcasses on the condition he would remove or burn the carcasses to avoid having a nusance to the detriment of the health of the neighborhood The deceased Logel without having obtained leave as petitioner did, to take the skins, was in the habit of taking the skins and leaving the carcasses on the ground neither removing or burning them This created a nusance for which petitioner was indicted and fined”

This tells us some important things about Civil War Louisville, specifically how it was a city spatially, demographically, and economically dominated by the war. Waves of German and Irish immigrants — presumably including Brockman and Logel — had settled in suburban rings outside the core of the old river town in the decade before the war. So when the war brought U.S. soldiers posted to garrison duty and, later, African American refugees fleeing slavery, the human geography of the city pushed out to and beyond the ring of forts on the map.

Sanitary conditions, we might well expect, were horrible as tens of thousands of soldiers and freedpeople crowded together into hastily built barracks, tents, and improvised shelters on poorly drained stretches of Jefferson County farmland. As with laws concerning fugitive slaves, the Louisville civil authorities applied existing public health laws to a human crisis far beyond the reach of local and state legislation to manage. Brockman had been fined for Logel leaving the carcasses to rot, but could Brockman really be blamed for a pile of dead animals the army dumped on near a creek? Bringing charges shows that the city was aware and concerned about the water supply but had no way to do much about the situation.

But what about Brockman’s agreement with the army itself? Other documents in the CWG-K collection suggest that Brockman may have been related to a family of German tanners in the city, which explains his job skinning the dead animals. His “contract” was one of the smallest interactions between the army and merchants, railroad corporations, and river men in the boom-town military micro-economy that sprung up in wartime Louisville. Brockman got horse carcasses, while the L&N — which shipped the poor animals to their final stop — raked in millions in wartime profit and limitless infrastructure work on bridges and tunnels paid for at the expense of the U.S. taxpayer.

“All of which your petitioner would respectfully submit and implore the exercise in his behalf of your Excellency’s clemency

“All of which your petitioner would respectfully submit and implore the exercise in his behalf of your Excellency’s clemency

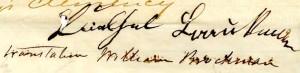

[signed]

translation William Brockman”

Even Brockman’s name needed to be translated and anglicized from its German fraktur script. Only at the end are we clued into the fact that while the petition is written in Brockman’s voice, these are far from his own words.

Moreover, while he is fascinating for scholars today, Brockman’s was probably one of the least important signatures on this petition to Governor Bramlette. William Brockman’s petition carried the weight of some of the leading former Whigs — and, therefore, former anti-immigrant Know Nothings — in Louisville politics and society. Stay tuned for a later post which will explore some of these men and why they would write on behalf of a German tanner’s assistant.

Patrick A. Lewis is Project Director of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.