Cross-posted from the KHS Chronicle.

The Civil War Governors of Kentucky project is deep into annotation, the phase of the project where each of the people, organizations, places and geographical features mentioned in every CWGK document is tagged, researched and linked together in a vast social network. I’ve written elsewhere about what that will look like from a research and technical perspective. Today, I want to focus on the research finds and unexpected questions that this work brings.

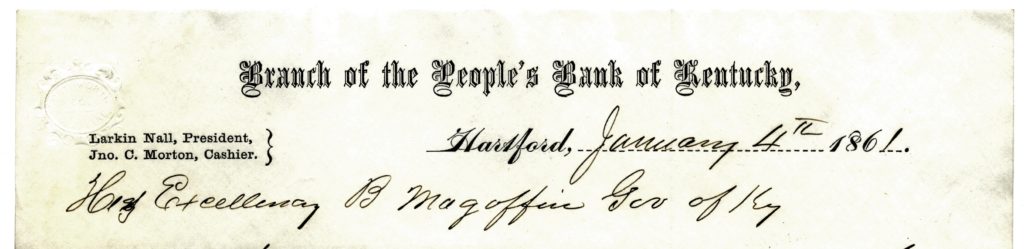

This week, I was working on this document, a letter from some Hartford, Kentucky, bankers, looking to have one of their own named a notary public in December 1860. Routine state business. Then I started researching cashier John C. Morton.

Not surprisingly, given the way small-town businesses work then and now, he is the older brother of the Alonzo L. Morton who has recently taken a job in the circuit court office. The two young professionals lived together with their father, Isaac Morton, when the census man came to town. Except he wouldn’t be living with his parents for long. On June 30, 1860, John C. Morton had travelled east to Frankfort to marry Sally J. Chinn, the daughter of prosperous farmer, Franklin Chinn. Everyone called her Jennie.

Jennie Chinn Morton c1910, KHS Collections, 1917.1

Now, the name Jennie Chinn Morton carries a certain connotation at KHS. She was the secretary-treasurer and later regent of the revived KHS of the late 19th century, the first editor of the Register of the Kentucky Historical Society and the driving force behind the establishment of this organization in permanent state offices in Frankfort, first in the capitol annex and later in the Old State Capitol itself. She shaped publications, research and collections. Jennie Chinn Morton was the Kentucky Historical Society.

This is not to hero worship. I have issues with her interpretation of the past and whose Kentucky stories she valued. I question the history she wrote and why she wrote it. But, her legacy as an institution builder is a model for any public history administrator. The Kentucky Historical Society has grown and evolved since Morton, but without her, the seed would never have been planted.

So, could this 21-year-old newlywed be that Jennie Chinn Morton? A quick search through our digital collections confirmed that it was. The finding aid to an 1893 diary, mentions that she was “Soon widowed after her marriage to John C. Morton of Hartford, Kentucky in 1860” after which she “turned her time and attention to literary pursuits.” Did she ever.

I still haven’t puzzled what happened to John Morton. Did he die of some summer disease right after their marriage? Did he rush off to enlist in one of the contending armies in 1861? Whatever the case, his death allowed one of Kentucky’s most influential femmes sole in 19th and early 20th century Kentucky to pursue work that was meaningful to her.

I wonder what would have happened if he had lived?