By Patrick A. Lewis

From what appears to be a spiritless case of operating a financial brokerage without a license in Thomas E. Bramlette’s pardon applications, we uncovered an unsung Civil War hero to the people of Bowling Green.

When the Confederate army occupied the counties of southern Kentucky and proclaimed a provisional government of the state in the winter of 1861-62, they could not claim the sympathies of all the residents. In Bowling Green, the capital of Confederate Kentucky, many Union citizens detested the rebel garrison and the shadow government which ruled the region. Unionist farmers were in especial danger. The large Confederate army needed supplies, “and to subsist it their authorities purchased” food, firewood, forage, and livestock. All of this was paid for in Confederate money, “which…said citizens were bound to accept or have their crops, stock &c taken without compensation & subjecting themselves perhaps to other dangers for refusing.”

But what would happen when the rebels left? Would banks and merchants honor these Confederate bills? How would these farmers feed and warm their families now that their winter stores had been paid for in money with no purchasing power? Not only were these farmers deprived of valuable agricultural products in the middle of the winter, but they were facing long-term financial ruin, too.

Sensing the desperate need of the farmers, local businessman H. P. Allen bought the Confederate money from his neighbors, redeeming the now-valueless paper bills in his own gold and silver coins at face value—saving the farm families from bankruptcy and utterly ruining his own fortune in the process.

A final insult came in 1864 when secessionist sympathizers had Allen convicted of operating a brokerage without a license. Without any funds to hire a skilled lawyer to defend him and unwilling to publicize his kindness by having those he had aided come testify in his defense, Allen pleaded no contest to the charges.

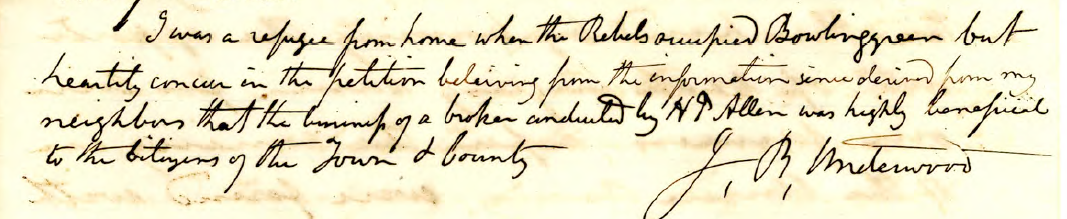

Yet just as Allen had come to the aid of the loyal men of Warren County in 1861, they rushed to defend him three years later. Allen’s friends—including Josie Underwood’s father, for Register readers—petitioned Bramlette to pardon the man who had proved himself “a positive good to the people” of his county. William V. Loving summed up their testimony:

I parted with, volentarily or otherwise, a good deal of stock & “truck,” generally whilst the rebels were here & had as a matter of course, to take Southern money but converted the Same into coin immediately & feel that the brokers done me & the public a great favor in purchasing the depreciated paper we were required to take & therefore unite in the prayer of the petition[1]

Whether it be greenbacks, the Internal Revenue, gunpoint bank robberies, economic depression, bank failure, or currency speculation, the Civil War Governors of Kentucky will be an unparalleled resource for understanding the financial vulnerability faced by all Kentuckians during the years when their state became a battlefield.

[1] William B. Jones, et. al to Thomas E. Bramlette, Aug. 3, 1864, Office of the Governor, Thomas E. Bramlette: Governor’s Official Correspondence file, Petitions for Pardons, Remissions, and Respites 1863-1867, Box 11, BR11-204 to BR11-205, Kentucky Department of Library and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.