Throughout January 2019 we shared a four part series discussing political detentions surrounding Kentuckians. In case you missed a week or are just stumbling upon the blog for the first time here are the direct links to the series.

Author Archives: CivilWarGovernors.org Admin

“Nothing on the Books”: Political Detentions in the Civil War Part Four

This is the final installment of a four-part series

As residents of Kentucky were arrested for disloyalty and detained, often for several months, without being charged or tried in criminal court, one of the most protracted cases was that of Covington attorney James J. O’Hara Jr. In its contours, the story of O’Hara’s initial detention resembles the accounts of other political prisoners whose stories are preserved in the papers of Kentucky’s Civil War governors. O’Hara was arrested at his home on July 22, 1862, by the Covington provost marshal and jailed at the Newport Barracks for more than a week. He was not immediately able to ascertain the reason for his arrest—a disturbingly common complaint among civilian prisoners. On July 30, he was sent to Camp Chase, where his story took a decidedly different turn and where he wrote letters to a person he addressed as “My Dear,” who was probably his wife, Oberia.[1]

In his personal correspondence, James O’Hara wrote of financial matters, requested provisions, and expressed affection for friends and family. He warned his recipient, “You must not come here to see me as the authorities will not allow visitors within the prison.”[2] He learned this when a friend had come to Camp Chase with the young son of Thomas L. Jones—who had been arrested for making fiery anti-government speeches—and the visitors were turned away. When several of O’Hara’s fellow prisoners petitioned Beriah Magoffin, they complained of this rule and of the hardship of being separated from their families.[3] Although O’Hara was acquainted with James Robinson and other state officers, he advised his correspondent against trying to involve them in his case, writing in one letter, “I do not think it worth while for you to apply to my friends Davis, Robinson and Harlan or any others at present, although I have no doubt those named would do all in their joint power to secure my release.” In another, he wrote, “I know of nothing that can be done at present by friends out side to deliver me.”[4] When newspapers reported a Confederate advance into Kentucky, O’Hara instructed his recipient to seek the advice of friends on the safest course of action, as he could not be sufficiently informed to offer useful counsel.[5]

Not surprisingly, the status of O’Hara’s case was a recurring topic, especially the difficulty of learning the charges against him. He tried to project a positive attitude while also preparing his spouse for an incarceration that he predicted could last several weeks or months. “I do not expect that the process [of discharge] will be instantaneous,” O’Hara cautioned, but he affirmed that his release was “certain in the end, as I know that I am guilty of no offense against the law.” Prescribing a course for both himself and his spouse, O’Hara resolved, “I shall exercise the utmost degree of patience, and trust that you will not allow our separation to weigh heavily with you.”[6] Two weeks after he applied to learn the charges on which he had been arrested, he still had received no answer. “I do not understand why I am not gratified in that particular as others have been,” O’Hara lamented, but he supposed it was “inadvertence and not design” that kept him uninformed.[7] O’Hara hoped his recipient would not allow her “buoyancy of spirit for a moment to flag” and reassured her that he would face his fate “undaunted.”[8] On August 21, three weeks after his arrival at Camp Chase, O’Hara reported that he had finally learned the reason for his arrest: “James O’Hara is charged with ‘being a rabid and dangerous rebel sympathizer.’ Has done ‘a great deal to aid the rebellion.’” He dismissed the allegations as unfounded. “Of Course there is nothing in these charges,” he assured his wife, and “there can be no difficulty about my release when the authorities can find the time to attend to our cases.” But he still had no idea when that might be.[9]

O’Hara may have downplayed the adversities of prison life so as not to worry his spouse. He offered a more candid account in 1863, when he provided testimony to a select committee on military arrests appointed by the Ohio House of Representatives. He specifically noted that both prisoners of war and citizen prisoners were “badly clad, not having changes of clothing.” He observed that the citizens “seemed to have been brought there without suitable preparation for a long continuance away from their homes.” He also told of two young boys, whose ages he estimated to be between eight and twelve, who had been imprisoned along with their father. According to O’Hara, when the father was arrested, the boys had no one else to take care of them on the outside and the father requested they be kept together.[10]

If James O’Hara was as confident of his release as he claimed in his letters, it did not prevent him from pursuing a more clandestine path to secure his liberty. When he was presented an opportunity to escape the confines of Camp Chase, James O’Hara took his chance. He was informed of an arrangement in which one of the prison sentinels had agreed to allow the escape of eight to ten prisoners and was invited to join the group, which he later admitted, he was “entirely willing to do.”[11] By O’Hara’s account, the sentinel, who was bribed with a gold watch and about twenty dollars, removed a plank from the parapet, leaving an opening for the prisoners to escape. O’Hara filed out behind Hubbard D. Helm, the former sheriff of Newport, who had been arrested on July 18 and accused of “making the statement of being a secessionist.”[12] Helm and O’Hara ran about fifty yards before they were surrounded by forty to fifty soldiers and ordered back to the prison.[13] As punishment, O’Hara was locked in a structure known as “the dungeon,” probably so named for the light deprivation and physical discomfort it likely imposed on its occupants. By O’Hara’s account,

I was put into a dungeon constructed of boards, about four feet wide by eight feet long, with seven feet ceiling. The door closed tight, and was secured with a hasp and staple and ordinary padlock. For ventilation there were five inch and a quarter auger holes through the bottom, and a hole in the top five inches square. This was roofed over, and inclosed in a house or shed, one of a number of like description.[14]

He was kept in this cell from about 10 p.m. Saturday night to sometime Wednesday afternoon. The first night, he was not given any blankets and “suffered severely from cold.”[15] The other prisoners who followed Helm and O’Hara out of the camp had managed to return to their quarters when it was clear the escape had failed. Colonel C. W. B. Allison, the camp commander, tried to persuade O’Hara to identify the other escapees, but he refused. O’Hara later recounted, “He [Allison] said my conduct in the matter would be the means of prolonging my stay in the prison.”[16]

In fact, O’Hara would be allowed to leave the prison the following month, around the same time as many other Kentucky citizens who had been arrested over the summer, but unlike most of the citizen prisoners who would be released on the condition of taking a loyalty oath or with the additional provision of a bond, O’Hara would retain the status of political prisoner and remain under federal authority much longer. He was paroled on October 18, 1862, but was required to remain in Cincinnati. When O’Hara’s case and that of another prisoner, W. S. Pryor, came to the attention of Abraham Lincoln in January 1863, the president directed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to “Let their parole stand, but allow them to go at large generally.”[17] O’Hara’s parole was expanded to all states loyal to the Union, which allowed him to return to Kentucky. As a condition of his parole, he was required to report his current location by weekly letter to the military commandant of Cincinnati.[18]Dutifully, every week, O’Hara wrote a letter, the text of which rarely deviated unless a change in his residence was reported in the return address.Commanders came and went, departments reorganized and relocated, the country embarked on uneasy peace, and still James O’Hara sent his weekly parole letters.[19]

Finally, in early 1866, O’Hara’s case again drew the attention of military authorities. In March, E. O. C. Ord, commander of the Department of the Ohio, wrote Brigadier General H. L. Burnett asking for information on O’Hara. The tone of his letter suggested equal parts perplexity and frustration at the lack of records in O’Hara’s case. “I can find nothing on the books in the Asst. Judge Advocate General’s Office, relating to this man,” Ord wrote, “and am called upon for a report as to who and what he is, why under parole, since when, and by whose order, with such other information as may be had concerning him and his offence.”[20] Burnett sent back two of O’Hara’s parole letters and informed Ord that it was only by mistake that the Adjutant General’s Office had received and filed the documents. Burnett had “no other records or knowledge” of O’Hara’s case.[21] Ord then ordered a broader investigation to identify and examine any records pertaining to O’Hara, especially for information about the reason for his arrest and continued parole.[22]

Twice during the investigation, James O’Hara was asked to provide statements summarizing the facts of his case, which could not be located elsewhere. In a letter dated April 3, 1866, O’Hara recounted his arrest, his incarceration at the Newport Barracks, his transfer to Camp Chase, and the terms of his parole. He wisely omitted any reference to the failed prison break, which in 1862-63 may have been considered sufficient cause to continue the parole, rather than grant his release. But the reason for his arrest remained a mystery even to James O’Hara. As he explained, “I in vain endeavored to obtain a Specification of the ground upon which I was arrested during my stay at Camp Chase and would now be most happy if you could inform me.”[23] In his letter dated August 8, 1866, O’Hara provided substantially the same statement but added one additional detail: “There were affidavits of two witnesses taken after my arrest, while I was yet in New Port Barracks, but they contained no specification of any offence alleged to have been committed by me but general charges of Disloyalty.”[24] His release was approved by the Secretary of War on September 5, 1866, more than four years after his arrest.[25]

Hubbard Helm, the twice-arrested former sheriff of Campbell County, who participated in the failed prison escape with James O’Hara, was discharged from federal custody in April 1863, while he was already on parole. Despite his checkered history as a person of suspected disloyalty, Helm’s case fell under General Orders, No. 193, issued in November 1862, which called for the release of political prisoners still in custody.[26] Helm filed a lawsuit against Henry Gassaway in Campbell County that was considered part of a coordinated effort to undermine federal authority.[27] Helm was re-elected to the position of sheriff in 1866, 1868, and 1870.[28] In 1868, Helm and several other men, including James R. Hallam, received corporate recognition from the Kentucky legislature as “The Newport Newspaper Company” for the purpose of starting a newspaper and printing office in Campbell County.[29] A biographical reference of prominent Kentuckians published in the 1870s described Helm as “at times absolutely controlling the politics of his county.” The article went on to note that during the Civil War, Helm “stood on the side of the South in principle and sympathy.”[30]

Thomas L. Jones, who was arrested for making incendiary speeches about arming his children and fighting the government, was also one of the litigants who filed a lawsuit against Henry Gassaway.[31] In 1867, he became one of several congressmen-elect from Kentucky to have their elections challenged in the U.S. House of Representatives on grounds that they were ex-Confederates or Confederate sympathizers. Jones was eventually allowed to take his seat.[32]

From 1868 to 1874, James O’Hara Jr. was a judge in the 12th District Circuit Court. In 1874, he resigned his judgeship and formed a law partnership with John W. Stevenson.[33] As governor of Kentucky, Stevenson had strongly opposed federal Reconstruction policies and was uncritical of the Kentucky legislature when it rejected the 15th Amendment granting African Americans the right to vote.[34]

In the system of political detentions adopted during the Civil War, an accusation of disloyalty or a critical—albeit, reprehensible—utterance or a misplaced suspicion could land a citizen in prison. The mechanics of that system offends a commonly held sense of justice that includes the presumption of innocence, due process, and the right of free speech. And yet…amid the military crisis Henry Gassaway described, of enemy forces advancing from multiple directions, and recognizing an imperative not to reveal the vulnerabilities of the Union position, should Gassaway have waited to see if someone like Hubbard Helm or Thomas Jones would betray those weaknesses to the enemy? Should he have waited to see if the tough talk of a man who reportedly wished the death of Union troops and another who reportedly declared his willingness to fight the U.S. government would translate into acts of treason? Or should Gassaway have taken those bellicose men at their word? After all, the opportunity to make war against the United States was on the march and about to breach the Union defenses at Newport. And yet… J. T. Boyle, William Sipes, and Horatio Wright all acknowledged that citizens innocent of wrongdoing, even as defined under the strict terms of Boyle’s original orders, could be and were mistakenly sent to prison.

The peculiar brand of loyalty that kept Kentucky

in the Union had been conditioned, largely, on white Kentuckians’ mistaken

belief that the federal government would preserve slavery and protect their

property rights in human beings. Feeling betrayed by emancipation, they

responded, after the Civil War, by electing ex-Confederates and Confederate

sympathizers to office.[35] At

least some of the former Camp Chase prisoners seem to have benefitted from this

change in political currents. Also in the postwar era, white Kentuckians

participated in campaigns of violence and intimidation against African

Americans in what Anne Marshall describes as an attempt to “restore as much of

the prewar social and racial order as possible.”[36]

It is beyond the scope of this series and of the CWGK to determine whether the experience of the Camp Chase

prisoners caused them to develop a more inclusive respect for individual rights

or whether it amplified their grievances and made them more defiant of the

policies of the federal government. But in light of developments in postwar

Kentucky, it is necessary to ask of the citizens who complained in 1862 that

their rights had been violated by incarceration: How many shared the postwar

proclivities of the majority of white Kentuckians? And how many attempted to

deny by legislative, judicial, or extralegal means, citizenship rights to the

formerly enslaved?

[1] James O’Hara Jr. to S. M. Barber, April 3, 1866, Letters Received by the Office of the Adjutant General, Main Series, 1861-1870, NARA Microfilm Series M619, Roll 500, File 0146, p. 13-14 accessed via Fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/301098886 (hereafter Letters Received); Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Kenton County, Covington Ward 4, p. 697.[2] KYR-0002-011-0004.[3] Robert Maddox et al., “Letter from Prisoners at Camp Chase to Governor Magoffin,” Journal of the Senate of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, Begun and Held in the Town of Frankfort, on Monday, the Second Day of September, In The Year Of Our Lord 1861, And of the Commonwealth the Seventieth (Frankfort, KY: Yeoman Office, 1861), 617. [4] KYR-0002-011-0001; KYR-0002-011-0004.[5] KYR-0002-011-0005. [6] KYR-0002-011-0004. [7] KYR-0002-011-0002.[8] Ibid. [9] KYR-0002-011-0005.[10] Testimony of James O’Hara Jr., “Report of Select Committee on Military Arrests,” appendix to House Journal, Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Ohio, vol. 59 (Columbus: Richard Nevins State Printer, 1863), 162.[11] Ibid., 162.[12] Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Campbell County, Newport, p. 551; The Biographical Encyclopædia of Kentucky of the Dead and Living Men of the Nineteenth Century, vol. 1 (Cincinnati: J. M. Armstrong & Company, 1878), 362; “Roll of Prisoners of War at Camp Chase Ohio,” Selected Records of the War Department Relating to Confederate Prisoners of War, NARA Microfilm Series M598, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, RG 109, Roll 24, p. 190, accessed via Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/interactive/1124/M598_24-0241; Case Files of Investigations by Levi C. Turner and Lafayette. C Baker, 1861-1865, NARA RG 94, Microfilm Series M797, Roll 0010, Case File 272, p. 12, accessed via fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/257090175. [13] “Report of Select Committee on Military Arrests,” 162. [14] Ibid., 163. [15] Ibid. [16] Ibid. [17] Abraham Lincoln to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, January 9, 1863, Kentucky Historical Society, SC103, http://kyhistory.com/cdm/ref/collection/MS/id/10068. [18] Letters Received, Roll 500, File 0146, p. 13-14, https://www.fold3.com/image/301098886. [19] For collection of letters see Papers Relating to Citizens, Compiled 1861 – 1867, NARA RG 109, Microfilm Series M345, Roll 0207. [20] E. O. C. Ord to H. L. Burnett, March 19, 1866, Letters Received, Roll 500, File 0146, p. 27, https://www.fold3.com/image/301098959. [21] Letters Received, Roll 500, File 0146, p.25. [22] Ibid. [23] James O’Hara to S. M. Barber, Letters Received, Roll 500, File 0146, p.14, https://www.fold3.com/image/301098890. [24] James O’Hara to Hugh G. Brown, Letters Received, Roll, 500, File 0146, p. 4, https://www.fold3.com/image/301098812. [25] Letters Received, Roll 500, File 0146, p.29, https://www.fold3.com/image/301098966. [26] Papers of and Relating to Military and Civilian Personnel, compiled 1874-1899, documenting the period 1861-1865, NARA RG 109, Microfilm Series, M347, Roll 0180, accessed via Fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/251924427. [27] Letters Received Roll 0370, File K250, p. 2, accessed via fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/301027826. [28] The Biographical Encyclopædia of Kentucky, 362.[29] “An Act to Incorporate the Newport Newspaper Company,” Acts of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, Passed at the Regular Session of the General Assembly, Begun and Held at the City of Frankfort on Monday, the Second Day of December, 1867, vol. 2 (Frankfort: Kentucky Yeoman Office, 1868), 188. [30] The Biographical Encyclopædia of Kentucky, 362.[31] Letters Received, Roll 0370, File K250, p. 2. [32] Ross A. Webb, Kentucky in the Reconstruction Era (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2015) 27-28. [33] H. Levin, The Lawyers and Lawmakers of Kentucky (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1897), 758. [34] Lowell Harrison, ed., Kentucky’s Governors (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004), 99.[35] Anne Marshall, Creating a Confederate Kentucky: The Lost Cause and Civil War Memory in a Border State (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 2, 10, 24, 33-34.[36] Ibid., 56.

Christina K. Adkins has a PhD in American Studies and works as a volunteer on the CWGK Team. Her work focuses on slavery and cultural memory.

More Dangerous than Open Enemies: Political Detentions in the Civil War Part Three

[This is the third installment of a four-part series]

Between July 1862, when Camp Chase began to receive large numbers of political detainees, and October 1862, when many of these cases began to be resolved, the prison received over 550 citizen prisoners, nearly half of whom were from Kentucky.[1] Among these Kentucky citizens was Edward Stevenson, a Methodist minister and Russellville resident who was arrestedon suspicion of being – as Stevenson himself later reported — “a rabbid, or prominent Secessionist” and chairman of a “Home Committee on Safety,” an organization erroneously presumed to have existed for the purpose of harassing Unionists.[2] Stevenson came under suspicion of Union forces, in part, for having participated in an ad hoc system of identifying supposed “dangerous” persons during the Confederate occupation of Russellville; ironically, that process closely resembled the one by which Stevenson later found himself incarcerated at Camp Chase.

In August 1862, Stevenson was one of 37 prisoners from Camp Chase Prison No. 1 who petitioned Kentucky governor James Robinson to intervene in what they clearly articulated as a violation of legal norms.[3] Earlier in the month, a similar petition signed by 93 Kentuckians in Prison No. 2 was addressed to Robinson’s predecessor, Beriah Magoffin, who in the interim, resigned the Kentucky governorship.[4]

In addition to signing that petition, Stevenson also appealed to Governor Robinson and federal officials through personal correspondence. In a letter to Robinson dated August 18, Stevenson acknowledged that he had served as chairman of the safety committee but denied that he was a secessionist. He regarded secession as a “rash and reckless course,” of which he strongly disapproved. He did, however, admit to opposing U.S. war policy, as he did not believe the shedding of blood was the best way to preserve the Union.[5] But he also claimed he had not made his sentiments publicly known. “If I ever cherished a disloyal sentiment, uttered a disloyal word, or performed a disloyal act,” Stevenson wrote, “I am not conscious of having done so.”[6] He justified his involvement with the safety committee, which had been appointed by residents of Russellville during the Confederate occupation, as being an agent of reason and restraint. His hope, he claimed, was “doing some good; and especially in protecting peaceable citizens, from the violence of misguided and reckless southern citizens and soldiers.”[7] Indeed, when he offered a detailed account of the workings of that committee to Joseph Holt—who was a few weeks away from being named judge advocate general of the army—Stevenson claimed that when the civil authorities of his town were displaced by the Confederate invasion, the committee had been formed with the intention of protecting peaceable citizens. He also noted that Unionists had expressed gratitude to the committee for the protections it had provided.[8] By Stevenson’s account, the Home Committee on Safety also served in a capacity similar to that of the U.S. special commissioner in the cases of political prisoners. Ordered to “arrest all dangerous persons found in the community,” the Confederate commander at Russellville, according to Stevenson, proposed that the safety committee review the cases and, if the committee judged the persons “peaceable citizens,” they would be “promptly discharged.” The committee, Stevenson recalled, regarded this arrangement as an opportunity for “the protection of the innocent and unoffending from personal and military violence” and readily accepted the responsibility. Perhaps with a hint to his own jailers, Stevenson noted that “all who were turned over to the comte were judged to be peaceable citizens, and with one exception, were all immediately released.”[9] The exception was a Mr. Finley, who was given a choice by the Confederate occupiers of taking an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy, becoming a prisoner, or being sent beyond Confederate lines. When Finley refused to take the loyalty oath or choose between the other options, the committee was asked to decide for him. They determined that sending him beyond Confederate lines posed the “least affliction” to Finley and his family, but their recommendation, according to Stevenson, was misstated as a “mandatory resolution,” which appeared to be the source of the claim that the committee had mistreated Unionists. The members eventually rescinded their decision, and Finley was allowed to remain in Russellville without being taken prisoner.[10]

Of the five members of the Committee on Safety who were subsequently arrested by U.S. authorities, only Edward Stevenson and one other, James McCallen, were detained and sent to Camp Chase.[11] When General Boyle was consulted about their applications for release, he recommended that McCallen be discharged on condition of taking a loyalty oath and executing bond. Without offering to expound on his claims, Boyle advised that Stevenson be detained, as he had “exerted all of his influence against the Government and has been a most pestilent disciminator of treason.”[12]

Russellville residents M. B. Morton and John B. Peyton corroborated Stevenson’s account of the Committee on Safety. In a letter signed by both men, they affirmed that “a vast amount of mischief and trouble was prevented by the labors of that committee.” Stevenson, they attested, “labored with unremitting efforts and with all his influence to those ends.”[13] In its first iteration, Peyton had served on the Military Board of Kentucky, an organization created primarily to prevent then-governor Beriah Magoffin from using the state’s military resources to support the Confederacy.[14] Peyton had also been one of the five members of the safety committee initially arrested along with Stevenson.[15] Their legal fates would continue to be entwined even after Stevenson’s incarceration.

On October 7, Reuben Hitchcock, the special commissioner appointed to examine the cases of civilian prisoners, issued his recommendation in Stevenson’s case. Hitchcock judged Stevenson to be “a man of considerable influence, of peaceble & quiet disposition, Southern Rights in his political Sentiments, but disposed to submit to and follow the actions of his State.” Hitchcock determined that Stevenson and most of the other members of the Russellville Home Committee on Safety had “labored fruitfully to prevent violence and outrage upon the person or property of either Union or Secession men.” Believing he could be “discharged without danger to the public peace & interest,” Hitchcock recommended that Stevenson be released on condition of taking an oath of allegiance to the United Sates and giving $3,000 bond as “security for his good behavior.”[16]

In light of that recommendation and Stevenson’s “greatly infeebeld health,” he was paroled to Columbus for ten days but feared the parole would expire before an order for release could be obtained. He appealed to Governor Robinson to request an extension from Ohio governor David Tod so that he would not be required to return to prison. “An other weeks confinement and exposure in that place will terminate my earthly existence,” Stevenson predicted. He also confided to Robinson that he was eager to “get Home and die in the bosom of the little remnant of my once hapy, but now deeply afflicted family.”[17] Stevenson was released from federal custody on October 20, 1862.[18] But his legal troubles did not end there.

Although the system of political detentions operated separately from the criminal justice system and typically did not result in prosecutions,Stevenson and John B. Peyton, the ex-Military Board member who was also involved with the safety committee, were indicted by a federal grand jury.[19] After Peyton successfully petitioned for a presidential pardon, Stevenson pursued a similar legal strategy.[20] Once again, Peyton lobbied on Stevenson’s behalf. Enlisting the aid of John B. Temple, a former president of the Military Board, Peyton wrote that he had witnessed Stevenson “going through inclement weather day and night, at his advanced age and in feeble health, to the camps and headquarters of the military to procure the release of arrested Union citizens.” Peyton added that after Stevenson’s “self-sacrificing and devoted efforts to prevent oppression and misrule,” for him to be made “the subject of cruel misrepresentation and rank injustice is particularly hard.” Peyton argued that even if Stevenson were “the man that cruel misrepresentation” had made him out be, his “long imprisonment in Camp Chase” should have been sufficient punishment.[21] Writing to Kentucky Congressman Henry Grider, Temple, who had known Stevenson since childhood, declared that it was “a stigma upon the government that men who banded themselves to alleviate the horrors of this war should be so pertinaciously pursued while so much greater offences were not so vigorously pursued.” Temple also recounted his discussions with U.S. attorney James Harlan. “I happen to know,” Temple wrote, “that Hon Mr. Harlan considered many indictments found by the Federal Grand Juries as not well founded & had declared his determination to dismiss this one—He told me that many indictments or true bills were formed when he was too much engaged to instruct the juries as to their duty.” Temple added that a Union military commander at Russellville had investigated the matter of the safety committee and found the members to be “guilty of no fault.”[22] President Lincoln ordered a pardon for Edward Stevenson on January 13, 1864. [23] Stevenson died nearly six months later, on July 6, 1864.[24]

As for the other Camp Chase petitioners who sought assistance from the Kentucky governor in the summer of 1862, in the majority of cases, they were released by the end of the year on condition of taking a loyalty oath. A few were required to take the oath and secure a bond in amounts ranging from $500 to $5,000.[25]

Advising a subordinate in February 1863, General Horatio Wright aptly explained the potential pitfalls of citizen detentions. He described a class of citizens in Kentucky who “while never having left their homes or taken up arms in the rebel cause have by their acts proved themselves enemies to the United States.” Wright did not elaborate on these acts but advised that on “proper proof,” such citizens should be arrested and sent with written charges to Camp Chase, adding that “many such [citizens] give no chance for obtaining evidence of their disloyalty, while they are notoriously disloyal.” Describing this group as “often more dangerous than open enemies,” Wright recounted how they were arrested when a “sound judgment indicated a necessity” and then released when the necessity had passed. But he also advised “great prudence” in exercising the power of arrest, as “individuals entirely innocent of any disloyal design may be arrested and imprisoned upon the evidence of the over-zealous patriot or the designing enemy.” Wright pointed to the “numerous discharges” of Camp Chase prisoners as evidence of this systemic flaw.[26]

Aside from the often arbitrary nature of political detentions and

the apparent lack of due process they entailed, the reports of a government

detectivealso call into question

their effectiveness in preventing acts of subversion. Posing as a Confederate

sympathizer in Lexington in the summer of 1864, Ed F. Hoffman made contact with

Daniel Wiehl, who was imprisoned in Camp Chase from August to December of 1862.

Wiehl apparently fell under suspicion at least one other time, as Hoffman

reported that Wiehl had taken the oath of allegiance twice.[27]

Hoffman’s dispatches indicate that, despite having sworn his loyalty to the

U.S., Wiehl provided information to Hoffman about a secret route taken by

recruits leaving Lexington to enlist in the Confederate army.[28]

It was not uncommon for residents to take the oath while concealing their true

sympathies.[29]

[1] Statistics Compiled from lists of prisoners received at Camp Chase for July-October 1862, Selected Records of the War Department Relating to Confederate Prisoners of War, 1861-1865, NARA RG 109, Microfilm Series M598, Roll 25, accessed via Ancestry.com.

[2] Edward Stevenson to James F. Robinson, 18 August 1862, Office of the Governor, James F. Robinson: Governor’s Official Correspondence File, Petitions for Pardons, Remissions, and Respites, 1862-1863, R3-105, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY, accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, http://discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0001-029-0065; M. B. Morton and J. B. Peyton to J. J. Crittenden, 10 July 1862, Case Files of Investigations by Levi C. Turner and Lafayette C. Baker, 1861-1865, NARA RG 94, Microfilm Series M797, Roll 0018, Case File #550, p. 19, accessed via Fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/257012348.

[3] Thomas S. Bronston, Jr. et al. to James F. Robinson, 19 August 1862, Office of the Governor, James F. Robinson: Governor’s Official Correspondence File, Military Correspondence, 1862-1863, R2-9 to R2-10, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY, accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, http://discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0001-027-0008.

[4] Robert Maddox et al., “Letter from Prisoners at Camp Chase to Governor Magoffin,” Journal of the Senate of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, Begun and Held in the Town of Frankfort, on Monday, the Second Day of September, In The Year Of Our Lord 1861, And of the Commonwealth the Seventieth (Frankfort, KY: Yeoman Office, 1861), 617; Lowell Harrison, ed., Kentucky’s Governors (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004), 80.

[5] Stevenson to Robinson.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Edward Stevenson to Joseph Holt, July 1862, Case Files of Investigations by Levi C. Turner and Lafayette C. Baker, 1861-1865, NARA RG 94, Microfilm Series M797, Roll 0018, Case File #550, p. 7, accessed via Fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/257012232.

[9] Stevenson to Holt, 7.

[10] Ibid, 9.

[11] Ibid, 10-11.

[12] J. T. Boyle to L. C. Turner, 21 August 1862, Case Files of Investigations by Levi C. Turner and Lafayette C. Baker, 1861-1865, NARA RG 94, Microfilm Series M797, Roll 0018, Case File #550, p. 33, accessed via Fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/257012459.

[13] Morton and Peyton to to Crittenden, p. 20.

[14] Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Kentucky, vol. 1, 1861-1866(Frankfort: Kentucky Yeoman Office, 1866), vii; E. Merton Coulter, The Civil War and Readjustment in Kentucky, chapter 7 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1926) Google ebook.

[15] Stevenson to Holt, 11.

[16] Reuben Hitchcock to L. C. Turner, 7 October 1862, Case Files of Investigations by Levi C. Turner and Lafayette C. Baker, 1861-1865, NARA RG 94, Microfilm Series M797, Roll 0018, Case File #550, p. 41, accessed via Fold3.com,https://www.fold3.com/image/257012521.

[17] Edward Stevenson to James F. Robinson, 11 October 1862, Office of the Governor, James F. Robinson: Governor’s Official Correspondence File, Military Correspondence, 1862-1863, R2-89, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY, accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, http://discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0001-027-0057.

[18] “Roll of Prisoners of War at Camp Chase Ohio,” Selected Records of the War Department Relating to Confederate Prisoners of War, NARA RG 109, Microfilm Series M598, Roll 24, accessed via Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/interactive/1124/M598_24-0246; “1862 List of Prisoners Released from Confinement at Camp Chase,” Selected Records of the War Department Relating to Confederate Prisoners of War, NARA RG 109, Microfilm Publication M598, Roll 26, accessed via Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/interactive/1124/M598_26-0280.

[19] Neff, Justice in Blue and Gray, 158; Edward Stevenson to H. Grider, 31 December 1863, Case Files of Applications from Former Confederates for Presidential Pardons (“Amnesty Papers”), 1865-67, NARA RG 94, Microfilm Series M1003, Roll 0026, Edward Stevenson File, p. 12, accessed via Fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/249/20662935.

[20] Stevenson to Grider, 12.

[21] John B. Peyton to J. B. Temple, 31 December 183, Amnesty Papers, compiled 1865 – 1867, NARA RG 94, Microfilm Series M1003, Roll 0026, Edward Stevenson File, p. 16, accessed via Fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/249/20662957.

[22] J. B. Temple to Henry Grider, Amnesty Papers, compiled 1865 – 1867, NARA RG 94, Microfilm Series M1003, Roll 0026, Edward Stevenson File, p. 17, accessed via Fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/20662965.

[23] Amnesty Papers, 1, https://www.fold3.com/image/20661838.[24] _Find A Grave_, “Rev Edward Stevenson (1797- 1864),” Memorial #123746647, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/123746647 (accessed October 15, 2018).

[25] “Roll of Prisoners of War at Camp Chase Ohio;” “1862 List of Prisoners Released from Confinement at Camp Chase.”

[26] H. G. Wright to Brigadier General White, OR, series 2, vol. 5: 300.

[27] Ed. F. Hoffman to J. P. Sanderson, OR, series 2, vol. 7: 302-303, 336; “Roll of Prisoners of War at Camp Chase Ohio Red During August 1862,” Selected Records of the War Department Relating to Confederate Prisoners of War, NARA RG 109, Microfilm Series M598, accessed via Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/interactive/1124/M598_24-0254.

[28] Ed. F. Hoffman to J. P. Sanderson, OR, series 2, vol. 7: 304.

[29] Christopher Phillips, “Netherworld Of War: The Dominion System and the Contours of Federal Occupation in Kentucky,” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, 110, no. 3/4 (2012): 343, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23388055.

Christina K. Adkins has a PhD in American Studies and works as a volunteer on the CWGK Team. Her work focuses on slavery and cultural memory.

Check back with CWGK every Monday in January to read a new editions to Political Detentions in the Civil War.

“Arrests Continue Very Much to Our Detriment”: Political Detentions in the Civil War Part Two

[This is the second installment of a four-part series, read part one here.]

In the summer of 1862, orders from General J. T. Boyle meant to identify Confederate sympathizers and persons who had demonstrated disloyalty to the Union set off a wave of political detentions of Kentucky citizens. The authority over these political arrests and investigations, which originally rested with the State Department, had been transferred to the War Department in February 1862.[1] Once incarcerated in Camp Chase, prisoners discovered they often had little recourse and few means to expedite their cases. As James Russell Hallam complained in his letter to Governor James Robinson, “I have sought in vain for some tribunal either civil or military before which I could have my case investigated.” Testimony of friends and neighbors, the lawyer seemed certain, would allow him to refute the “the false & scandalous charge” against him, which, he insisted, was “unsustained by any shadow of evidence.”[2] Hallam had sent a petition to the War Department that swore his loyalty to the United States government, along with supporting affidavits, all the while “praying a speedy investigation.”[3] Assuming the delayed reply meant his case had been overlooked, Hallam asked Robinson to intercede.

He appealed to the governor’s knowledge of him over their long acquaintance. “You have known me personally for twenty years,” Hallam wrote, “& I feel confidant I am in your opinion, entitled to some sort of credence when I positively & solemnly assert that I have been guilty of no act or word disloyal to the Government under which I was born.” “On the contrary,” Hallam insisted, “since the rebellion began I have to the best of my ability & opportunities sustained the cause of the Union & abhored & repudiated secession & the rebellion.” Lest he leave any doubt, Hallam declared, “My earnest wishes & hopes are for the speedy crushing of the rebellion & the restoration of the Union as it was.”[4] After he wrote his initial appeal, Hallam realized that though they were long-acquainted, Robinson had no first-hand knowledge of his position on secession. He wrote a follow-up letter the next day, August 19, in which he named the Kentucky Adjutant General and two state senators as character references to support his claims of Union loyalty.[5]

Hallam’s eagerness to clear his name and to enlist anyone and everyone he thought could help him do it are not surprising, given that his arrest on July 18, 1862, was his second detention on suspicion of disloyalty. He was arrested on October 5, 1861, and held in federal custody until December 4 of that year. He took the oath of allegiance upon his release and claimed to have “lived faithfully up to it, both from duty and inclination” ever since.[6] Amid the July military emergency, Hallam volunteered to defend Newport. While helping “in good faith” to organize the defense of his hometown, he was arrested by Henry Gassaway and sent to Camp Chase.[7] All of this he wrote to Edwin Stanton on July 25, along with assurances of his support for the Union. “I deny the constitutional right of secession [and] look upon & denounce secession as a crime,” declared Hallam, who added that he had “sympathized with the United States government in the present rebellion.”[8]

Hallam also explained to Stanton why he though his loyalty had come under scrutiny. Over his objections, three of Hallam’s sons had enlisted in the Confederate army. “I declare that my sons joined the rebel cause against my strong remonstrances desire & command,” Hallam wrote.[9] Since their enlistment, two had been captured and imprisoned—one at Alton, Illinois, and the other at Camp Morton, Indiana. While advocating for his own release, Hallam had also been trying to talk some sense into his wayward children. “Since their capture,” he wrote to Stanton, “I have been untiring in my efforts to reclaim them to their allegiance to the U.S. & I think I have succeeded. My letters to them & their answers to me will sustain me.”[10]

Despite his best efforts, Hallam’s release would not happen quickly. The War Department was only just appointing a special commissioner to investigate the cases of the Camp Chase political prisoners. Reuben Hitchcock was notified of his appointment on August 13.[11] His instructions from the War Department, dated August 23, were to interview each prisoner and examine evidence related to the person’s guilt or innocence and their “intentions toward the Government whether loyal or hostile.” He was directed to make a report that included his recommendation “as to whether the peace and safety of the Government requires [the prisoner’s] detention or whether he may be discharged without danger to the public peace.” The War Department advised Hitchcock that he was granted “the largest discretion” in his investigative powers and except in rare circumstances, his recommendations would be followed. Hitchcock was also advised that the War Department wished to “forbear the exercise of power,” as much as possible without sacrificing the security of the government.[12]

Although in June he had opposed the release of Camp Chase political prisoners on grounds that it hampered the efforts of the Union army in Kentucky, by early August, General J. T. Boyle complained that “Prisoners [were] sent to prison for the most trivial causes by provost-marshals” who had ostensibly been acting on his orders.[13] Boyle found that he was unable to secure the release of even Union men whose loyalty could be vouched for by the U.S. attorney.[14] Such arrests for “trivial causes” strained an already tenuous political situation in Kentucky. On August 12, J. B. Temple, President of the Military Board of Kentucky, warned Abraham Lincoln that “indiscriminate arrests” played poorly on public sentiment. Specifically, Temple objected that “Quiet, law abiding men holding State-rights dogmas are required to take a [loyalty] oath repulsive to them or go to prison.”[15] The next day, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton communicated to Boyle that the power to arrest Kentucky civilians should be “exercised with much caution and only where good cause exists or strong evidence of hostility to Government.”[16]

In response, Boyle again attributed the problem to the actions of provost marshals, some of whom he had appointed and others of whom were already in office when he took command. According to Boyle, “many arrests are made by provost-marshals without my authority and in some cases without proper cause.” He explained that in some cases, the provost marshals had sent the prisoners to Camp Chase, where he had no control over the prisoners. He reminded Stanton that he had already asked the War Department for authority over the Camp Chase prisoners, presumably so he could secure the release of loyal Unionists wrongfully incarcerated but also those who had been “sent to prison for special purposes of public interest” who remained in prison after the perceived threat had passed. Boyle complained that “For some reason this control of the prisoners is withheld from me.” But he also insisted that some of the arrests were justified. “There are many so-called Union men in Kentucky who still cling to the hope of reconciliation and believe in a policy of leniency,” he explained, although the general strongly opposed such a policy. “I believe in subjugation,” Boyle declared, “complete subjugation by hard and vigorous dealing with traitors and treason.” “Any other policy,” he predicted “will be ruinous to us in Kentucky.” Although he expressed willingness to adopt any policy the President or Secretary of War directed regarding arrests, he added that it was only “lukewarm Union men” who complained.[17]

A little more than a month later, on September 15, James Robinson and Joshua Speed directed messages to President Lincoln urging that the authority for arrests be placed with the Kentucky governor. The “irregular and changing system of military arrests,” claimed Robinson, “does more harm than good.”[18] Speed, a longtime friend of Abraham Lincoln, reported that “Annoying arrests continue very much to our detriment.” He advised the President, “The good of the cause requires that you should direct Boyle to leave this whole matter to our loyal Governor.”[19] Later that day, Edwin Stanton ordered Boyle to “abstain from making any more arrests except upon the order of the Governor of Kentucky.”[20] In reply, Boyle insisted that he had been sparing in his use of the power of civilian arrest and that reports to the contrary were false. He repeated his claim that the complaints were made by men of questionable loyalty. And he declared that “There is a bounty of absolute security and protection to be a rebel in Kentucky.”[21] Boyle warned that if the government did not “put down the rebels in our midst…the war will have to be fought over in Kentucky every year.”[22] As it was, the general reported that in Louisville, Confederate flags were thrown from windows “with impunity,” and he defiantly informed the Secretary of War that he had countermanded the order regarding arrests.[23]

Although Boyle seems to have borne the blame for those operating under his command, other accounts support his contention that some provost marshals were, as Stanton later described, “rigorously and excessively arbitrary and harassing to the people of Kentucky.”[24] Instances were reported of provost marshals making arrests and accepting bribes to release the prisoners, actions Stanton condemned as “inexcusable outrages.”[25] Indeed, in October, he directed that provost marshals found to have abused their authority in such a manner should, themselves, be arrested.[26] On December 18, 1862, Lt. Colonel William B. Sipes, the military commander at Covington and Newport who assumed the post in September, acknowledged that the power to arrest and imprison civilians had been “too indiscriminately exercised,” but he also noted that regular military officers were rarely the problem; more often, the arrests had been made by civilian provost marshals. “The will of these gentlemen was the law,” Sipes wrote, “and in many instances they appear to have exercised their official functions with but little regard for any rule of action either civil or military. Many of them kept no records, and instances are not rare where prisoners were confined by their order for months without the shadow of a written charge of any kind against them.”[27] He also described instances in which provost marshals had confiscated property. “Cases are known,” Sipes, reported, “where the effects of individuals were seized and appropriated without any military or legal sanction and in violation of all principles of justice and right.”[28] Sipes blamed such practices for “much of the bad feeling” in Kentucky and recommended that instead of civilian appointees, the provost marshal positions be filled by regular army officers.[29]

One provost marshal, Henry Gassaway, would become the target of multiple civil lawsuits by people he had arrested for disloyal conduct. In April 1865, Gassaway was the defendant of at least twenty-one lawsuits filed in Campbell County Circuit Court, each one seeking damages for false imprisonment in the amount of $50,000. Gassaway turned to the War Department for help and, in explaining his situation, provided a detailed account of his actions as provost marshal and the military emergency that led to several arrests. Gassaway’s account casts him, not as a rogue provost marshal, but a public servant who dutifully followed the orders of General Boyle. Gassaway wrote that the plaintiffs filed their lawsuits around the same time “as if acting in concert” and that the cases had continued as though “Originating in a desire to obstruct military operations and having the Effect of Embarrassing and oppressing the constituted authorities of the Government of the United States.”[30] Gassaway had the right to have the lawsuits removed to federal court, but Judge Advocate A. A. Hosmer had another idea. In a similar case, the Bureau of Military Justice had concluded that it was “competent,” under the proclamation of marital law, for the general commanding the military district of Kentucky to “restrain, by such means as in his discretion might be deemed needful” the continuation of nuisance lawsuits filed against U.S. officers for actions taken in the course of their duties. Hosmer advised that General Palmer, then in command of Union forces in Kentucky, could “take a needful action,” implying that he could simply re-arrest the troublemakers.[31]

The problem William Sipes described, of civilians being imprisoned for months without so much as a written charge against them, was contrary to Boyle’s original order, but that appears to be what happened to James R. Hallam. Although his appeal to Governor Robinson suggests Hallam had not yet received it, the Commissary General of Prisoners, William Hoffman, penned a letter to Hallam dated August 10. Hoffman acknowledged receipt of a letter Hallam had sent him directly; one that Hallam had sent to Ohio governor David Tod, which had been forwarded to Hoffman; and the petition that Hallam had sent via the Camp Chase post commander, presumably the one Hallam mentioned in his letter to James Robinson. Colonel Hoffman assured Hallam that his case had been referred to the Secretary of War “in a way if possible to secure speedy action upon it.” He also advised Hallam that he would probably be required to obtain affidavits from friends in Kentucky to establish his loyalty.[32] To move the process along, Colonel Hoffman had inquired into the charges against Hallam and two other political prisoners.[33] The answer he received was that there were no charges against Hallam. The colonel concluded that “there would therefore seem to be no reason for his further detention.”[34] That was on August 14, 1862, before Hallam wrote to the Kentucky governor. But Hallam was detained for two more months. He was required to take an oath of allegiance and finally released on October 14, 1862.[35] The following year Hallam filed a lawsuit in Kenton County against Henry Gassaway and several other men for wrongful imprisonment. His civil suit continued at least through April 1864, but no record of the final judgment has been located.[36] Whether or not Hallam’s was the earlier case referred to by the judge advocate, given A. A. Hosmer’s advice on how to deal with the coordinated lawsuits in Campbell County, it is doubtful that Hallam’s lawsuit met with any more success.

[1] Neff, Justice in Blue and Gray, 157.

[2] James R. Hallam to James F. Robinson, 18 August 1862, Office of the Governor, James F. Robinson: Governor’s Official Correspondence File, Military Correspondence, 1862-1863, R2-3 to R2-4, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY. Accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, http://discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0001-027-0005.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] James R. Hallam to James F. Robinson, 19 August 1862, Office of the Governor, James F. Robinson: Appointments by the Governor, Military Appointments, 1862-1863, R2-116 to R2-117, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY. Accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, http://discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0001-028-0003.[6]

James R. Hallam to Edwin Stanton, 25 July 1862, Case Files of Investigations by Levi C. Turner and Lafayette C. Baker, 1861-1865, NARA RG 94, Microfilm Series M797, Roll 0007, Case File 193, p. 6, accessed via Fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/257035312

[7] Ibid., 5

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., 5-6.

[11] Edwin M. Stanton to Reuben Hitchcock, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of theUnion and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1880-1901), series 2, vol. 4: 380 (hereafter OR).

[12] L. C. Turner, “Instructions for Hon. Reuben Hitchcock, special commissioner to investigate and to report on the cases of state prisoners held in custody at Camp Chase,” OR, series 2, vol. 4: 425.

[13] Jeremiah T. Boyle to Edwin M. Stanton, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 17; Jeremiah T. Boyle to Edwin M. Stanton, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 412 (quote 412).

[14] J. T. Boyle to Edwin M. Stanton, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 412.

[15] J. B. Temple to Abraham Lincoln, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 378.

[16] Edwin M. Stanton to Jeremiah T. Boyle, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 380.

[17] Jeremiah T. Boyle to Edwin M. Stanton, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 412-13.

[18] James F. Robinson to Abraham Lincoln, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 517.

[19] James F. Speed, to Abraham Lincoln, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 517.

[20] Edwin M. Stanton to Jeremiah T. Boyle, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 517.

[21] Jeremiah T. Boyle to Edwin M. Stanton, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 517.

[22] Ibid., 517-18.

[23] Ibid., 518.

[24] Edwin M. Stanton to Horatio G. Wright, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 616.

[25] Edwin M. Stanton to Horatio G. Wright, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 616.

[26] Joshua F. Speed to James F. Robinson, 14 October 1862, Office of the Governor, James F. Robinson: Governor’s Official Correspondence File, Military Correspondence, 1862-1863, R2-95 to R2-96, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY. Accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, http://discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0001-027-0045.

[27] William B. Sipes to Horatio Wright, OR, series 2, vol. 5: 96.

[28] Ibid., 96-97.

[29] Ibid., 97.

[30] Letters Received by the Office of the Adjutant General, Main Series, 1861-1870, NARA RG 94, Microfilm Series M619, Roll 0370, File No. K250, p. 6, accessed via Fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/301027835.

[31] Ibid., 8.

[32] William Hoffman to James R. Hallam, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 371-72.

[33] William Hoffman to Col. S. Burbank, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 365.

[34] William Hoffman to C. P. Buckingham, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 391.

[35] “Roll of Prisoners of War at Camp Chase Ohio,” Selected Records of the War Department Relating to Confederate Prisoners of War, NARA RG 109, Microfilm Series M598, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Roll 24, p. 190-91, accessed via Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/interactive/1124/M598_24-0241.

[36] Kenton County Circuit Court, Covington, Order Books, 1845-1977, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, March 9, 1863-April 16, 1864, 291, 344, 357, 557.

Christina K. Adkins has a PhD in American Studies and works as a volunteer on the CWGK Team. Her work focuses on slavery and cultural memory.

Check back with CWGK every Monday in January to read a new editions to Political Detentions in the Civil War.

“Without Warrant or Law”: Political Detentions in the Civil War Part 1

On the afternoon of July 18, 1862, Newport, Kentucky, attorney James Russell Hallam was arrested at his home by the city’s provost marshal and “a large body of armed regular soldiers.”[1] When he demanded to know the charges against him, Hallam later recounted, the provost marshal refused to tell. Hallam was taken under guard to the U.S. Barracks at Newport and held overnight. The next morning he and several other Kentucky citizens were sent to Camp Chase prison in Columbus, Ohio, where Hallam wrote to Kentucky Governor James Robinson that he had been “closely confined ever since & deprived of my liberty.”[2] Writing a month after his arrest, Hallam also reported what he had learned from the post commander about the cause of his imprisonment: He was “charged in general terms with disloyalty, to the United States Government” but, by Hallam’s account, “no specific act or word of disloyalty” had been named against him.[3]

Amid the crisis of civil war, Kentucky civilians like Hallam became political prisoners, arrested—often on vague allegations of disloyalty—and imprisoned without ever being legally charged with a crime. Political detentions, which occurred mostly in border states, were meant to be preventative and usually did not lead to criminal prosecutions. Once a person was in custody, an investigation determined whether sufficient evidence of disloyalty existed to merit further incarceration; if it did not, the prisoner could be released, usually on condition of taking a loyalty oath.[4] Ideologically speaking, “disloyalty” was not strictly limited to overt support for the Confederacy but could encompass opposition to various facets Union war policy.[5] The imprisonment of Hallam and dozens of other political prisoners who petitioned the Kentucky governor from Camp Chase in the summer of 1862 reflected a deeply flawed system of identifying dissidents, one that threatened to worsen an already tenuous political situation in Kentucky.

In August 1862, a total of 130 Kentucky citizens signed two petitions—one generated in each of two prison barracks at Camp Chase—declaring they had been wrongfully incarcerated and asking the assistance of the Kentucky governor. Both petitions argued the illegality of the arrests and the denial of due process to which the signers had been subjected. The petition from Prison No. 2 was dated August 6 and addressed to Beriah Magoffin, who would soon resign his office. Ninety-three inmates of Prison No. 2 asserted that they were taken to Camp Chase “by the force of arms, against our will and consent, in violation of the laws of Kentucky and the laws of the United States.”[6] They declared they had been arrested “without warrant or law” and noted that many had “been in confinement for a long time, with no hope of being released or having any hearing before any tribunal.”[7] They insisted that they were “law-abiding citizens of Kentucky and the United States,” that they had “not violated the laws of either,” and that their imprisonment was “unjust, both in law and in the eyes of God and man.”[8] The prisoners hoped the Kentucky legislature would “take speedy action” to assist them and “not allow her sons to rot in prison, without charge or crime of any kind.”[9] On August 19, 1862, thirty-seven prisoners from various parts of Kentucky who were incarcerated in Camp Chase Prison No. 1 similarly declared that they had been arrested “without warrant and without legal authority, in violation of law and their civil and legal rights, & forced out of the State of Ky.”[10] The petitioners insisted that they were “unlawfully held” at Camp Chase, and that they had “always been law, abiding citizens of the State of Ky, and [had] never committed an act of disloyalty against that State or the United States.” Yet they claimed they had been told by a prison official that they could “only regain our liberty by proof establishing our innocence — a principle unprecedented and unknown to the law.”[11]

Historian Stephen C. Neff identifies August and September of 1862 as having the highest rates of political arrests during the Civil War. This time frame coincided with the first efforts toward conscription, the issuance of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, and the first national suspension of habeas corpus. Martial law measures were also adopted that allowed detention for interfering with Union enlistments and for the highly subjective offence of “disloyal practices,” which generated what Neff describes as a “veritable orgy of detentions.”[12] Camp Chase records suggest detentions in Kentucky began to escalate slightly earlier, in July 1862. James R. Hallam was one of 28 Kentucky citizens and 7 Newport residents who arrived at Camp Chase from the Newport Barracks on July 19. On July 22, the prison received another 25 residents of Newport or Campbell County. For the entire month of July, the prison received 153 civilian prisoners from Kentucky, only 21 of whom arrived before July 15. In August, 50 prisoners arrived from Kentucky; in September, the number fell to 40.[13]

The orders of General Jeremiah T. Boyle demanding that certain categories of Kentucky citizens report to provost marshals to take loyalty oaths, coupled with a heightened military threat in the summer of 1862, precipitated the spike in citizen arrests. Boyle prefaced his June 19 directive with the statement that “peaceful and law-abiding citizens and residents of the State must be protected in their persons, property, and rights.” But anyone who had joined the Confederate forces, given them assistance, or crossed their lines without the proper permissions and since returned were ordered to appear before provost marshals in Louisville, Bowling Green, Lexington, or Paducah. These citizens were then required to “furnish evidence of… repentance, and take the oath of allegiance, and give bonds and security for their future good conduct.” Persons who failed to report would be “arrested and committed to the military prison at Louisville, and sent thence to Camp Chase” with a written record of the charges against them. There, they would wait for further action by the Secretary of War. Boyle also instructed that “In times of trouble like these, good, law-abiding men will refrain from language and conduct that excite to rebellion.” Allowing a wide latitude for interpretation, he prescribed arrest for “anything said or done with the intent to excite to rebellion.”[14]

A confluence of military events also accounted for an increase in arrests, particularly in northern Kentucky, where Campbell County provost marshal Henry C. Gassaway proved highly effective in identifying and removing potential disloyal persons. On July 18, the day James Hallam was arrested, and in the days following, Gassaway executed what might be considered mass arrests of suspected disloyal persons. When he was later called upon to defend his actions, he insisted he was acting on Boyle’s orders in the midst of a military emergency. Two days before the arrests, Georgetown had been captured; a day after that, the battle of Cynthiana had been fought. On the 18th, Paris had been captured by John Hunt Morgan. According to reports in Newport, Morgan had 3,000 troops and was coordinating with General Marshal, who was advancing with his own large force from the eastern part of the state. At the same time, Kirby Smith was moving in from the south, and, as Gassaway recalled, he “very soon thereafter drove our lines back to within four miles of Cincinnati.” The situation in Newport was growing dire. On the day of the arrests, by Gassaway’s account, the telegraph wires were cut, the railroad captured, and “rebel Scouts were threatening the southern line of the County.”[15] As Gassaway recalled,

The Commandant of the Post and the Barracks ordered their officers to prepare for an immediate attack and sent out Scouts and pickets along every approach to the City. A few days previously the guns in the fortifications around the hills of the city had been spiked and dismounted. The defences around the city were weak, and the union soldiers few and undisciplined. It was important that our true condition of Weakness should be Kept from the Knowledge of the Enemy. A large number of the fighting Union men of the Vicinity had been sent to the defense of the interior. 75 Home Guards of New Port were in the battle of Cynthiana, and on the morning of the 18th news came that they had met with defeat and disaster which added much to the Excitement and alarm of the people.[16]

In June, Henry Gassaway had received the circular containing Boyle’s orders about how to deal with suspected disloyalty. It included a letter from John Boyle, the Assistant Adjutant General, who advised Gassaway to “arrest and send to Camp Chase a few of the most violent and rabid secessionists.” [17] Gassaway was told to send a report to headquarters, and the matter would be settled. During the crisis in July, Gassaway telegraphed General Boyle asking if he should make arrests of “persons then considered dangerous.” The answer he said he received was, “‘arrest them certainly.’”[18]

Apprehended in the roundup of “dangerous” citizens was Hubbard D. Helm, the former sheriff and current master commissioner of the Campbell County Chancery Court.[19] It was not Helm’s first arrest. With one brother in the Confederate army and another described as a “rebel agent abroad,” Helm had been arrested in November 1861. As reported in a memo compiled from records of the State Department, which had authority over political arrests at the time, Helm was accused of expressing the “strongest secession sentiments” and the hope that “Union troops on their way to the interior of Kentucky would never return alive.”[20] Since that incident, Helm had not tempered his public comments. An affidavit sworn by an acquaintance of Helm’s in July 1862 claimed that Helm had been overheard talking with some men when news was reported that Fort Donelson had been captured. According to the witness’s statement, Helm replied that the news was “a damed lie and that any man that took that up was a liar and a sun of [a] Bitch.” When subsequent news was received of the defeat of Union troops, the witness reported, Helm seemed “Elated and Gratified.” Helm’s frequently observed “manner and conduct,” the witness concluded, “Showed that he was the enemy of the Government and that he desired the Success of the Southern Confederacy.”[21]

Another name on the Prison No. 2 petition was Robert Maddox. The same memo that shows Helm’s prior arrest also shows that one Robert Maddox was arrested on the same day as Helm in November 1861 for making statements similar to Helm’s. On July 3, 1862, Henry Gassaway wrote General J. T. Boyle that Robert Maddox “is a man of meanse and has great influence with his money particularly in this neighborhood and uses it freely to effect his end.” Gassaway considered Maddox “a dangerous man to our Government” and suggested if he were “held for some time it will do much good in quelling outbursts among the Rebels in this County.”[22] The four affidavits Gassaway sent to support the case against Maddox were not filed with his letter, so it is not known upon what evidence he based his conclusions. The 1860 census for Campbell County shows three Robert Maddoxes, who in 1862 would have been 18, 46, and 50 years old, but none match the 43-year-old Maddox who, prison records show, was arrested on July 1, 1862.[23] Although it is uncertain if that was the same Robert Maddox who was earlier accused of volubly wishing the deaths of Union troops, both arrests illustrate the kind of opposition the U.S. forces encountered from the Kentucky citizenry and the perceived offenses that were thought to justify political detention.

Also among the people detained in July 1862 was Thomas L. Jones, a Newport attorney and politician who did not petition the Kentucky governor. In a sworn affidavit, William H. Wagner attested that he heard Jones make two political speeches and described one in which Jones declared that his father’s remains were in South Carolina, that his interests and sympathies were with the South, that he would arm his two sons—who were about ten and twelve years old at the time—with revolvers and “put them on his father’s Grave,” and that Jones would “take a Sword and fight the for the South.” When Wagner next met Jones, he questioned him about these remarks, saying he thought Jones was a Union man. According to Wagner, “He [Jones] said I am a union man, but he said our rights have been trampled on and I am ready at any time to fight against any Black Republican Government.”[24] The comments reported by Wagner are a reminder that in Kentucky, a citizen’s allegiance could be a complex proposition, at times a shocking blend of Union ardor and virulent racism or a fidelity strained by passionate disagreements with Union war policy.

Christina K. Adkins has a PhD in American Studies and works as a volunteer on the CWGK Team. Her work focuses on slavery and cultural memory.

Check back with CWGK every Monday in January to read a new editions to Political Detentions in the Civil War. Continue reading

CWGK Symposium Storify Recap

Follow the discussions from the June 2017 CWGK symposium as they evolved in real time!

CWGK Graduate Research Associate Hannah O’Daniel created this Storify recap of the sessions in the Old State Capitol. More recap coverage is coming soon, and the papers will appear in an upcoming issue of the Register of the Kentucky Historical Society!

Making Connections to the Past

By Stefanie King

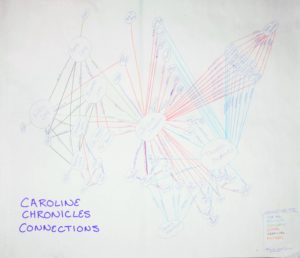

Civil War Governors‘ new Early Access web interface provides researchers access to thousands of transcribed Civil War-era documents that bring new voices into conversation with historians. But how does the project move beyond the texts to provide researchers new levels of access to the lives of 1860s Kentuckians? Early Access is an important achievement for the project, more than five years in the making. Yet the next phase of work will push the boundaries of digital scholarship by using these documents to map the social network of Civil War-era Kentucky.

This summer, Civil War Governors is trying to understand how dense and interconnected a network the documents will allow us to construct. So we chose 21 documents to be our laboratory experiment before moving on to the 23,000 identified so far.

Those 21 documents contained 440 identifiable entities (IDs), including people, places, and organizations. Some of the people mentioned in the documents are easy to identify, such as the governors or other prominent members of society. Others are harder. Caroline Dennant, from The Caroline Chronicles, is is difficult to research due to the biases of the historical record, stemming from her life as an enslaved woman and then as a contraband. Most of what we know about Caroline comes from the context of the documents in which she is mentioned.

Other people are difficult to identify because of how they appear in a document—for example, the “german woman” referred to in Caroline’s court case will be tough to identify because the information about her is vague (KYR-0001-004-0131). Similarly, many of the people mentioned in the documents are difficult to identify because their full name is not included. A Kenton County petition signed by “R Mann” is a start. But is he Robert Mann or Richard Mann, both of whom lived in the county at the time? (KYR-0001-020-1405). As frustrating as it can be, though, the process of identifying little-known historical actors includes some interesting discoveries as well, such as Willis Levy’s neighbor and brother, James, who was a lightning-rod maker.

Understanding how the people are connected is a challenging task as well. One obstacle, again, stems from the limitations of the historical record. For example, we know Rev. John L. McKee met with Caroline Dennant on multiple occasions, primarily providing her with religious counsel. But were they close friends, or merely acquaintances? Without further information from the people themselves, we can only determine the nature of that relationship as revealed in the extant documents. Furthermore, the documents do not tell us why Rev. McKee decided to help Caroline. Did Caroline seek out his counsel? Did a member of Rev. McKee’s congregation request that he become involved in Caroline’s case? Did McKee and Caroline already know each other somehow? Although we know there was a relationship between Rev. McKee and Caroline Dennant, we do not know how the relationship began, or what became of that relationship.

This leads to the second step in understanding the social network in Civil War-era Kentucky, which is categorizing types of relationships. Some relationships are easy to understand: Willis and Anne Levy were married; Blanche Levy was the child of Willis and Anne Levy; Anne Levy and Josephine Lynch were sisters.

Other relationships are not as easy to categorize. For example, numerous concerned citizens petition Governor Bramlette, asking that he pardon Caroline Dennant. But what is the nature of the relationship between these petitioners and Caroline? Are the petitioners friends of Caroline? Acquaintances? Some of the petitioners, such as John G. Barret, did not even know Caroline, and Caroline may not have known all of the people who petitioned the governor on her behalf (KYR-0001-004-0129). To complicate things further, nine of the jurors involved in Caroline’s case petitioned Governor Bramlette to pardon Caroline. The jurors who convicted Caroline of murder, then petitioned that she be pardoned. What type of relationship does that indicate? “Juror” or “petitioner” may not constitute a relationship, but the action of serving on the jury or signing a petition does establish a connection between them.

Deciding how to classify a huge range of human relationships into a handful of regularized relationship types is a tricky process that balances usability and nuance, generality and specificity. If Civil War Governors gets it right, researchers will be able to discover new patterns that would otherwise not be apparent, as well as have access to a new biographical encyclopedia of everyday people of all walks of life in Kentucky history. The project will allow researchers to visualize Civil War-era Kentucky by revealing the connections that underpinned this nineteenth-century world.

Stefanie King is a Ph.D. student at the University of Kentucky and a summer 2016 intern at the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.