By Jon Tracey

(former CWGK intern)

While working through document transcription, we are sometimes lucky enough to find several documents all related to the same topic. Often, these new documents provide a glimpse at previously obscured narratives in the documentary record. In this case, a small collection of letters from the 13th Kentucky Volunteer Infantry Regiment (U.S.A.) details a politically inspired conflict within the ranks. In March 1863, Union officials promoted Colonel Edward H. Hobson, the 13th Kentucky’s commander, to the rank of brigadier general which left his post vacant. The regiment’s second in command, Lieutenant Colonel William E. Hobson, was the natural choice for the colonelcy, but his accession to command proved problematic and sparked a potential mutiny.

Many factors surrounded the debate about who would be promoted. Age was one of William Hobson’s potential detriments. Other members of the regiment, including several officers, urged the promotion of Major Benjamin Estes, an older and more respected officer for promotion. Despite his youth, 17 at the time of recruitment, William Hobson had helped raise the regiment and secured an appointment as Major. Comparatively, Benjamin Estes, was a native of Bridgeport and a doctor who entered service with the regiment as a captain commanding Company D, and by the time of the promotion debate in 1863 was 31 years old, fourteen years William Hobson’s senior.[1] Though most who preferred another candidate acknowledged William Hobson’s management skills, talent and ability were discussion points during debate as well. He had only been lieutenant colonel for about a month, as his predecessor John Carlisle had resigned in mid-February. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, William Hobson was the nephew of Edward Hobson, and appeared to share his Republican political views.

One major argument made against the younger Hobson’s promotion was his young age. Though it is debated who the youngest Union colonel really was, William was certainly one of the youngest considered for the position. In the same letter that Edward Hobson wrote the governor thanking him for the promotion to brigadier general, he immediately set forth his nephew William as the naturally successor to the position of colonel. Edward Hobson even attempted to head off criticism regarding age, stating “Some persons would and I understand have urged as an objection his age. I have never found it an objection and of course have had every opportunity of judging.”[2] To further bolster his argument, he mentioned two other colonels stating they were similar ages to William and had given satisfactory service.

Command ability was another factor considered during promotion. The elder Hobson explained he knew “of no one more Suitable to fill my place” and that William was “one of the best young men in the State possessing all the qualities of a true Soldier and Gentleman.”[3] Even the officers who advocated for Estes’ promotion admitted that Hobson was a good officer, calling him a “good disciplinarian, and has brought the Regt to what it is.”[4] Another letter stated, “you know Lieut Col. Hobson is the man to fill that place, and is entitled to it by seniorarty[sic] and is the best military officer in the Regt.”[5] A.G. Hobson took a more direct approach in his letter supporting William. He directly referenced that the “Revised Regulations USA Page 11 Article 4 Sect 19 reads ‘All vacancies in established regiments and Corps’ to the rank of Col Shall be filled by promotion ‘according to Seinority[sic] except in Case of disability’ or other incompitency.[sic]”[6] In addition to defenses of his age and quoting regulations, other letters praised William’s organizational ability and bravery at the battle of Shiloh as further justification. Age aside, William seems to have been effective at his work.

Perhaps more important than even age or ability were William Hobson’s family ties and political affiliation. Edward Hobson, a veteran of the U.S.-Mexican War, raised the 13th Kentucky Regiment in the fall of 1861 and commanded it through several engagements until his promotion to brigadier general in early 1863.[7] He was an influential man. William E. Hobson was his nephew, the son of Edward’s brother Atwood Gaines Hobson.[8] This family connection certainly helped William, and he had used this prominent connection to recruit men and secure the position of major as the regiment was raised.

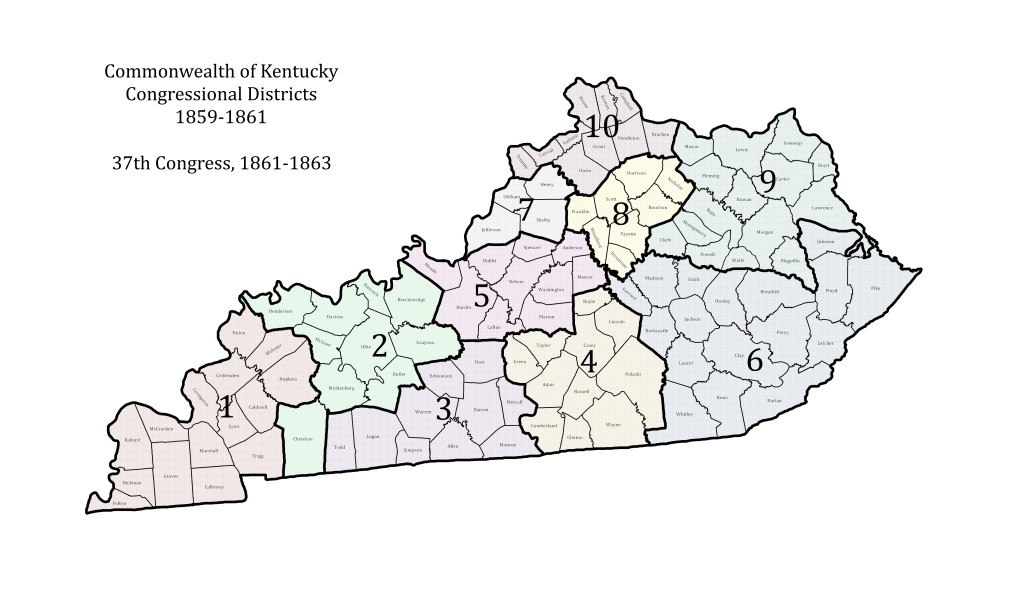

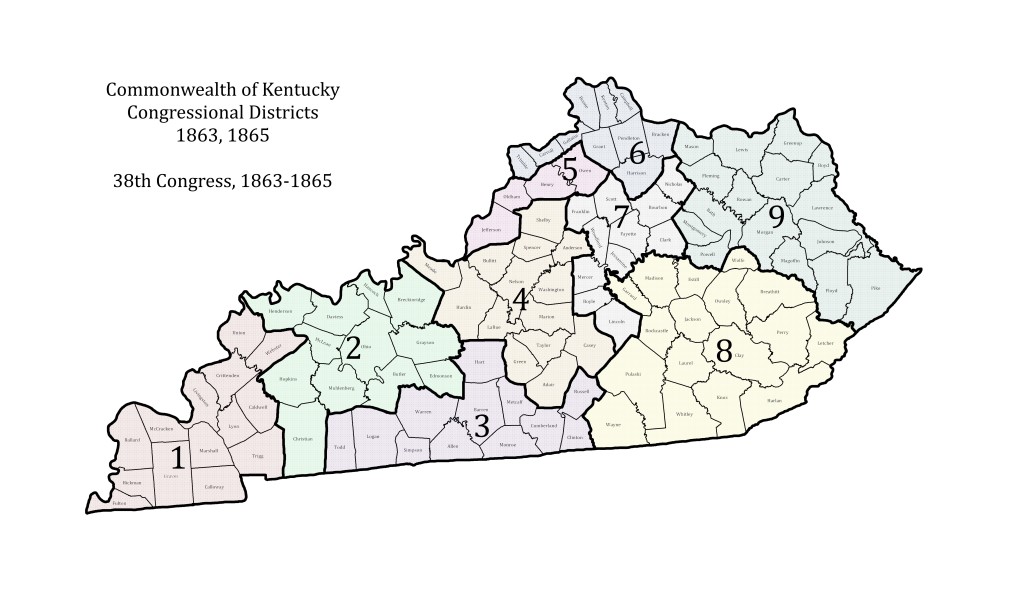

As explored by Zachary Fry in his book, A Republic in the Ranks, national politics often influenced interactions and promotions within a regiment.[9] Edward Hobson later joined the ranks of the Radical wing of the Republican Party after the war, supporting the 13th and 14th Amendments. Immediately after the war, he ran as the Radical Republican candidate for clerk of the state court of appeals, losing due to his support for the 13th and 14th Amendments, and later served in President Ulysses S. Grant’s administration as a district collector of internal revenue.[10] A biography of William Hobson published in the 1886 edition of Kentucky: A History of the State mentioned that after the war he began a Republican newspaper, indicating his wartime political affiliations.[11] This indicates that both uncle and nephew held similar views, and perhaps Estes was more politically conservative. Importantly, one of the newspapers that the “mutineer” officers sent their resolution to supporting Estes was to the “Journal & Democrat,” most likely the Louisville Daily Journal and the Louisville Daily Democrat, leading papers in the state’s largest city.[12]

The timing of the debate is also important, as it emerged in the aftermath of the Emancipation Proclamation. As Jonathan White argued in Emancipation, the Union Army, and the Reelection of Abraham Lincoln, the policy of emancipation often divided Union soldiers, especially those from border states.[13] Additionally, Fry explained that political views, especially those that supported the Republican Party’s national or state governments, could lead to promotion. Some who hoped for promotion “had learned that espousing Republican ideals was the quickest way to gain recognition.”[14] In another case, Fry noted that notably Democrat-leaning troops often found their promotions refused or delayed.[15] Though detractors tended to focus on the younger Hobson’s age as the primary reason he should not take command, political considerations also produced resentment against his promotion.

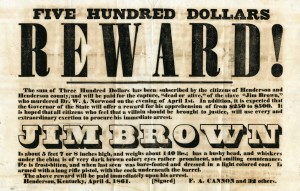

Interestingly, the material record sheds light on a surprising development that some considered a rebellion. On March 15, A. G. Hobson, likely Atwood Gaines Hobson (Edward’s brother and William’s father), sent a letter accusing several officers of conducting a “mutiny” by nominating Major Estes for the colonelcy.[16] See CWGK document KYR-0002-050-0013, which discusses this alleged mutiny. In it, several officers, led by Surgeon C.D. Moore and Lieutenant E.P. Allen, drew up numerous resolutions. They congratulated Edward on his promotion and requested to remain attached to his command. However, they also set forth Major Estes as successor, stating he held his “various positions with honor & ability and [is] one who is well worthy of the position.” [17] This resolution was signed by multiple officers, and copies were sent not only to Edward Hobson and Adjutant General John W. Finnell, but also to two newspapers for publication. Despite the resolution’s claim that they represented the officers of the regiment, several worked avidly to ensure William’s promotion. E.P. Allen wrote to Captain Patterson shortly after the meeting and complained that “Those men hold their meetings night and day for the purpose of forcing Maj Estes into that position.”[18] Clearly the section of the regiment that preferred Estes was both active and vocal.

In the end, army regulations won out. William Hobson was promoted to the rank of colonel on March 24, and Benjamin Estes took his place as lieutenant colonel. Hobson took the oath to fulfill his duties as colonel on March 26th, a document that is now part of CWGK’s digital collection as KYR-0002-050-0003. Despite the debates, William’s promotion to colonel was backdated to March 13, meaning he had effectively served as lieutenant colonel for a total of less than a month. In The Gentlemen and the Roughs, Lorien Foote explored a similar, but decidedly more violent, case of promotion-related tensions in the 7th Kentucky Volunteer Cavalry Regiment (U.S.A.). Major William W. Bradley, a well-loved officer with Republican sympathies, and Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Vimont, who was vehemently anti-abolitionist, of that regiment were bitter rivals.[19] Inflamed by partisan discord, the two men also bristled over a promotion. When the position of lieutenant colonel was open in 1863, two-thirds of the regiment’s officers signed a petition supporting Bradley’s candidacy for promotion. Despite this, influential politicians in the state government ensured Vimont’s promotion. Yet, Vimont “could not accept the obvious preference nearly every man in the regiment had for Bradley.”[20] Bradley was court-martialed for killing Vimont in January 1864, following a series of increasingly aggressive actions by the lieutenant colonel. Ultimately, Bradley was found not guilty of murder, as Vimont’s verbal and political aggression, accusations, and threats meant Bradley had acted in self-defense.[21] In the 7th Kentucky Cavalry, politics and personal tension led to a much more violent conclusion than in the 13th Kentucky Infantry.

Most of the 7th Kentucky’s “mutineers” appear to have continued service with the regiment without much continued conflict. However, Surgeon C.D. Moore, one of the most vocal proponents of Estes, was dismissed from service in June “with loss of all pay and allowance, for giving certificates of disability for discharge in cases of enlisted men, on insufficient grounds.”[22] Oddly, he was reinstated roughly two months later on August 11.[23] Perhaps his removal had been arranged by those who opposed that faction, but although Moore lacked enough influence to have Estes promoted he apparently had enough influence for his reinstatement. In any case, it seems internal politics troubled the 13th Kentucky months after the tensions of mid-March. Though William Hobson’s promotion occurred quickly, Benjamin Estes’s was delayed. Estes’s promotion to lieutenant colonel came later, dated May 15 of that year, perhaps a holdover of the tensions regarding the events of that March.[24]

In June 1864, William Hobson took command of the brigade the regiment was serving with, and Estes finally had command of the regiment he had tried to lead. Edward was briefly captured by Confederate Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan before taking command of Lexington, Kentucky. Following brigade command, William took a post in Bowling Green, and both Hobsons finished the war behind the lines. Estes commanded the 13th Kentucky until it mustered out on January 12, 1865, but he never received a promotion to colonel.[25] Perhaps this “mutiny” had doomed any chance of permanent promotion. The drama surrounding this promotion offers insight into the unusual internal politics within the Union Army. Whether driven by ambition, personal ambitions, or national politics, regiments seldom functioned as smoothly as might have been hoped.

[1] “Dr. Benjamin P Estes,” Find A Grave, November 2011, Accessed December 2020. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/80361096/benjamin-p-estes

[2] The documents used for this blog have only recently been transcribed and have not yet been processed onto the main website for CWGK. To find them, go to the FromThePage site for CWGK at https://fromthepage.com/khs/civil-war-governors-of-kentucky. From there, you can find the documents using the KYR numbers cited in these footnotes. KYR-0002-050-0001

[3] KYR-0002-050-0001

[4] KYR-0002-050-0011

[5] KYR-0002-050-0011

[6] KYR-0002-050-0005

[7] “Edward Henry Hobson,” Find A Grave, October 2001, Accessed December 2020. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/5894138/edward-henry-hobson

[8] “William Edward Hobson,” Find A Grave, July 2008, Accessed December 2020. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/28021515/william-edward-hobson

[9] Zachary A. Fry, A Republic in the Ranks: Loyalty and Dissent in the Army of the Potomac (Capel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2020).

[10] John E. Kleber, editor, The Kentucky Encyclopedia (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1992), 435.

[11] J.H. Battle, W.H. Perrin, and G.C. Kniffin, Kentucky: A History of the State, 1886 in M. Secrist, Warren County, Kentucky: History Revealed Through Biographical and Genealogical Sketches of its Ancestors (Morrisville, NC:Lulu Press, 2013).

[12] KYR-0002-050-0013

[13] Jonathan W. White, Emancipation, the Union Army, and the Reelection of Abraham Lincoln (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2014).

[14] Fry, 123.

[15] Fry, 145.

[16] KYR-0002-050-0005

[17] KYR-0002-050-0013

[18] KYR-0002-050-0011

[19] Lorien Foote, The Gentlemen and the Roughs: Violence, Honor, and Manhood in the Union Army (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2010), 59-60.

[20] Foote, 62

[21] Foote, 59-63.

[22] KYR-0002-050-0036

[23] KYR-0002-050-0038

[24] Daniel Lindsey, Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Kentucky Volume I (Frankfort, KY: John H. Harney, Public Printer, 1866), 855.

[25] Ibid,.