By Matthew C. Hulbert

On Monday, April 1, 1861, a Henderson County physician, Dr. Waller Norwood, emerged from his home and matter-of-factly ordered a waiting slave to fetch his mount. The unnamed servant obeyed Norwood’s command; in the stable, however, he found more waiting than his master’s horse. Encamped in the hay loft, with little intention of coming down, was an African American man owned by Mrs. Saraphine Pentecost. Here were two men in different stages of enslavement—one still in a state of submission, at least physically, as the other waged a one-man revolt for emancipation—brought face-to-face by a fluke encounter. However random, or harmless, it might appear at first glance, the events set in motion by their meeting would drive the paranoia of Kentucky slaveholders to new heights and raise serious questions about the mortality of their Peculiar Institution as civil war engulfed the nation.

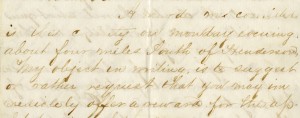

Puzzled by the news of a squatter in his stable, Norwood went to investigate for himself and did, indeed, find a man encamped in the hay loft. When asked to state his business, “the Negro replied that he had run away some days before from his mistress.” This declaration seems to have angered the doctor; he immediately ordered the runaway to climb down and surrender himself. According to an account of the incident later sent to Beriah Magoffin, then governor of Kentucky, the “negro replied by sundry threats” and refused to cut short his escape. Further enraged by this show of defiance, Norwood “then ordered the servant who was holding his horse to bring him his gun.” If the runaway wouldn’t come down from his perch peacefully, the doctor was determined to capture and return him to the Pentecosts by force.

The resolution would prove fatal.

As Norwood waited for a firearm, “the negro sprang towards him” and “at the same time shot him through the left breast, with a large dueling pistol.” The doctor “fell dead in his tracks.” Having heard the report of the gun, Mrs. Norwood came to investigate. She shrieked and sobbed hysterically at the sight of her slain husband—but his killer quickly pulled yet another pistol and she fled the scene. Norwood’s killer, who was eventually identified as Jim Brown, briefly admired his handiwork and “after leisurely viewing the dead body of the murdered man,” he “made for the woods.”

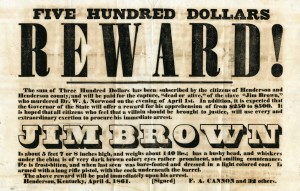

News of the assassination swept through Henderson and into surrounding counties. A well-respected white man—himself a slave owner—had been gunned down by an escaped slave. Posses formed, bloodhounds were summoned, and a coterie of outraged citizens convinced Magoffin to authorize a $500 bounty on Brown’s head. It could be earned dead or alive. Odds seemed to favor dead. As one spectator noted, “it is the universal opinion, that if taken, he will be immediately punished, without a moments hearing” as “those in search of him are armed with double barrel shotguns and will in all probability shoot him down upon sight.”

After a burst of activity, Brown’s trail went cold. For days, posses hunted the surrounding counties and turned up nothing. Varying descriptions of the fugitive circulated widely. One listed him as “about 5 feet 9 inches tall … weighs one hundred and fifty pound … quick spoken and fond of talking.” Another added that Brown had “a bushy head,” “whiskers under the chin,” was “of very dark brown color,” and distinguished by “eyes rather prominent.” With $500 on the line and so many men on the hunt in and around Henderson, Brown’s sole chance at permanently escaping bondage seemed to lie across the border in Indiana. But for reasons never fully explained, he actually stayed within a few miles of the scene of the crime, traveling by night and hiding in lofts and outbuildings during the day.

Eventually, the pursuers caught a break: they stumbled across an elderly slave woman who confessed to feeding Brown and pointed the posse in the direction of his last known hideaway—a nearby hayloft. Brown’s options quickly went from bad to worse. On one hand, he’d be returned to his master and made to stand trial. He’d be executed, no doubt, but might live for a few weeks in the meantime. On the other hand, he might throw down his gun and simply be killed on the spot. So as armed men surrounded the farm and cut off all routes of escape and then began searching the barn, Jim Brown decided to die fighting and initiated a skirmish he knew he couldn’t win. Very shortly afterward, he was dead.

In hindsight, the reaction to Norwood’s death shouldn’t surprise us. In any state that allowed slavery, the shooting of a white man by a runaway slave was going to elicit a thunderous response, especially from the slaveholding community. But in Kentucky, the skies were particularly volatile.

For his part, Magoffin tried to keep Kentucky “neutral” as other Upper South and Border West states slipped from the Union. And while Kentucky did ultimately remain within Lincoln’s grasp, the main impetus for doing so came from Conservative Unionists—men who weren’t necessarily interested in Unionism or sake of the Union itself, but simply because they believed the Union would be better suited to protect their investments in human chattel. This positioned Magoffin squarely between the proverbial rock and hard place.

The public had branded Jim Brown a “desperate and bloodthirsty villain” from the start. So the fact that sentiment skewed toward a swift, terrible, and if need be, extra-legal, brand of justice for Norwood’s slaying, shouldn’t much surprise us either. One petitioner, writing a day or so after the murder, went so far as to caution the governor not to be cheap with his reward amount, lest important constituents start to consider him weak on the issue of slavery and find support elsewhere. “Exercise your discretion in offering a reward,” the letter stated, but “considering the character of the offense, and the excitement of the country on the slavery question, I think the larger the reward is the better.”

As we already know, Magoffin offered a sizable $500 bounty and didn’t require that Brown be taken alive. Put another way, based almost entirely on the word of people involved in the situation (and hopelessly biased), the governor issued posses a license to lynch the fugitive on site and to be paid for their services as vigilantes. These terms, along with Brown’s demise, temporarily reassured Kentucky slaveholders that their wealth was still safe under the umbrella of the Union—but they also set an exceedingly dangerous precedent concerning what future concessions masters would expect in exchange for their loyalty and good behavior.

Taken in a much broader context, covenants such as these were partly responsible for the chaos that enveloped Kentucky in 1863–1864. When it became necessary for Abraham Lincoln to close the loophole that allowed the state to avoid fulfilling its quota of black troops for the Union Army, men who’d become accustomed to swapping their political loyalty for sake of maintaining a preferable social and economic status quo learned a hard lesson: by the time Lincoln changed the terms of the deal, their greatest bargaining chip—the threat of secession—had lost its power. The temper tantrum that ensued came in the form of guerrilla warfare.

Matthew C. Hulbert is an Assistant Editor of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.

SOURCES: Alex H. Major to Beriah Magoffin, 3 April 1861, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY (hereafter KDLA); L. W. Trafton to Beriah Magoffin, 9 April 1861, KDLA; Robert Glass to Grant, 4 April 1861, KDLA; F. A. Cannon, Reward Notice, 4 April 1861, KDLA; Robert Glass to Beriah Magoffin, 4 April 1861, KDLA; Jim Brown Fugutive Slave Reward, 12 April 1861; Beriah Magoffin, Executive Journal, 12 April 1861, KDLA; Edmund L. Starling, History of Henderson County, Kentucky (Henderson County, KY: 1887), 558-561.

For more on the history of Henderson and Henderson County, Kentucky, check out Volume 113 (Autumn 2013) of the Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, available through Project MUSE.