Click on a governor’s name or photo to view his expanded bio.

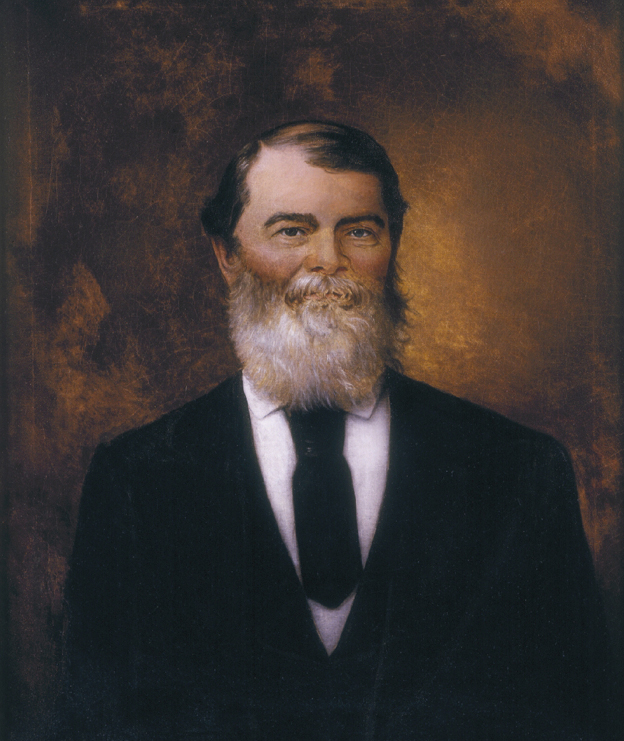

Beriah Magoffin 1859-62

Party: Democrat, Southern Rights.

Residence: Harrodsburg, Mercer County

Occupation: Lawyer and Farmer

Like many Kentuckians, Beriah Magoffin found himself torn between his interests, sympathies, and loyalties during the secession crisis. He joined most white Kentuckians in opposing Lincoln’s election in 1860, but joined the conservative proslavery majority in the state-roughly two-thirds of the voting population-to advise against secession and rebellion while still hoping to protect the rights of slaveholders at home and in the territories. His December 1860 exchange with Alabama Secession Commissioner S.F. Hale is a classic statement of Kentucky’s anti-secessionist pro-slavery philosophy-a great irony in light of his eventual sympathy for the Confederate cause.

Refusing Lincoln’s April 1861 call for volunteers to suppress the rebellion, Magoffin led Kentucky into a period of official, armed neutrality. For months, the state militia refused to allow United States or Confederate military personnel into Kentucky, while political battles raged in a legislature divided over the question of secession. Magoffin’s not-so-secret secessionism won him no favors with the emerging Unionist majority as 1861 wore on, particularly among the former-Whigs who resented seeing a Democrat in the governor’s mansion.

After Unionists captured the legislature in August and declared Kentucky’s unconditional loyalty to the United States in September, they set about relieving Magoffin of many executive powers. During the spring, the legislature had created a Military Board, with Magoffin as president, to oversee the state’s armed forces. Yet after September, fearing that Magoffin would delay the recruitment of loyal troops, the governor was demoted, first to a voting member of the board and later removed altogether. The relationship between the General Assembly and the governor remained sour. Magoffin routinely vetoed war measures only to have his veto overridden by the loyal majority time and again. As Confederates invaded the state in the summer of 1862, Magoffin was pressured to resign. He did, but only on the condition that he hand-pick his successor, State Senator James F. Robinson-a Unionist but one committed to protecting the interests of slaveowners. Magoffin largely removed himself from wartime politics, spending the war at home or overseeing business in Chicago, though he later served one postwar term in the General Assembly.

Magoffin’s papers make an excellent place to begin understanding how Kentuckians reacted to and shaped the secession crisis. In addition to his personal communications with Washington, neighboring governors, and the legislature, nearly every part of his official papers testify to the deep divisions within the state. Military commissions are sought by men hoping to put down the rebellion and resigned by officers going to fight for it. Notes of support for both the Union and the Confederacy appear on pardon petitions and applications for notaries public. Magoffin’s papers, too, provide CWGK’s best glimpse of the last few months of antebellum slavery in Kentucky. Through these records, we see traces of an Upper South slave society alive and well, before rumors of emancipation, invading armies, and the assertiveness of enslaved Kentuckians began to weaken slavery across the state.

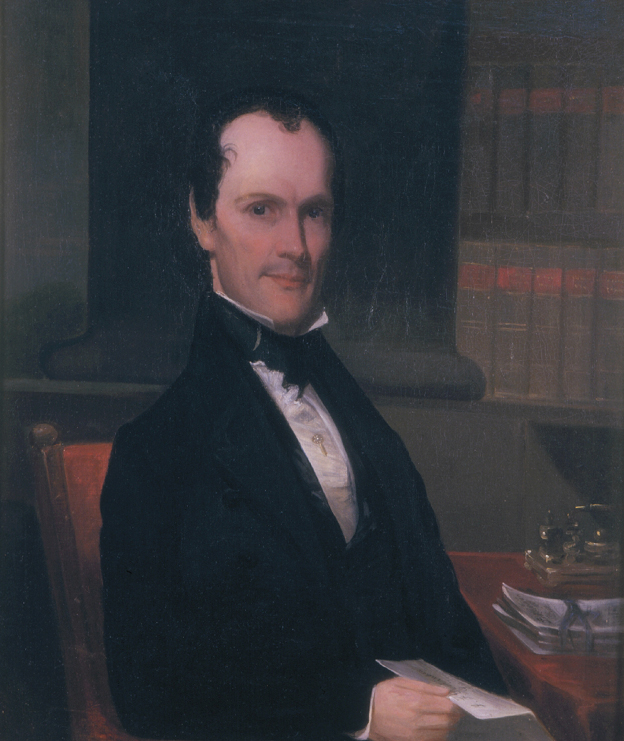

James Fisher Robinson, 1862-63

Party: Whig, Unionist.

Residence: Georgetown, Scott County.

Occupation: Banker and Lawyer

It is tempting to see James F. Robinson’s short term as governor as an interlude between the excitement of Magoffin’s secession crisis and Bramlette’s titanic battles with the Lincoln administration. Robinson’s administration, however, spanned the year on which all of Kentucky history arguably turned-the pivot point when slavery began to collapse along with the faith of many white Kentuckians in the federal government. He was elected via a legislative coup, first retreated from and later repelled a major Confederate invasion of the state, and set the tone for conservative Unionist resistance to Washington’s emancipation measures.

Robinson was elected to the State Senate in the August 1861 election that finally secured Kentucky for the Union cause. Though Robinson was one of Magoffin’s ex-Whig Unionist opponents in the legislature, when Magoffin was being pressured to resign in August 1862 he would only do so if Robinson replaced him. The gubernatorial line of succession was complicated. Magoffin’s Lieutenant Governor, Linn Boyd, had died in 1859, just over a month into the term, making the Speaker of the Senate next in line. But Magoffin thought the sitting speaker-John Fisk, a New York native who represented Covington-insufficiently conservative and worried that Fisk might too zealously crack down on secessionists or inadequately defend the property rights of slaveowners. With a solidly proslavery record and hailing from a county with large numbers of rebel soldiers and sympathizers, though, Robinson was acceptable to the governor. So, over the course of just two days, Fisk resigned; Robinson was elected speaker; Magoffin resigned; Robinson became governor; and the former speaker was re-elected. This seemed to all be nominally constitutional, though Robinson never resigned his seat in the Senate and technically held both that and the governorship simultaneously.

The new governor immediately found himself in a critical situation. Two major Confederate armies slipped around and through Union defenses and invaded the state within months of his election. As one of those armies, containing Confederate provisional governor Richard Hawes, marched on Frankfort, Robinson was forced to abandon the capital and flee to Louisville. Hawes was inaugurated at what is now the Old State Capitol, but the rebels did not stay long. Union armies converging from the south and north drove the Confederates from the state after the battle of Perryville-the largest and most significant Civil War battle fought in Kentucky-in early October.

Robinson presided over a state forever changed by that invasion. Not only had the rebels hauled away a wealth of Kentucky food, goods, and livestock, but the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation shook Kentucky’s slave society to its core. Though the proclamation did not apply to loyal Kentucky, enslaved people took it as a sign that slavery was coming to an end. They often found allies in Union reinforcements sent from northern states to repel the Confederate invaders. Unionist slaveowners were outraged when federal military officials sat silent as thousands of enslaved Kentuckians found refuge within Union lines, and from that time on both the institution of slavery and the faith of many white Kentuckians in the federal government went into a steep decline.

Both as governor and, later, when he returned to the Senate, Robinson proved the articulate defender of the legal rights of slaveowners that Magoffin had hoped he would be. His finely crafted constitutional arguments, though, stood little chance against the historical tide which had been turned during his administration. His papers are CWGK’s window into one of the most important crisis years in Kentucky history.

Thomas Elliott Bramlette, 1863-67

Party: Whig, Union Democrat.

Residence: Columbia, Adair County.

Occupation: Lawyer and Judge

Thomas Bramlette’s administration was the longest of the five CWGK governors and is the best documented. It is fortunate that Bramlette’s time in office is so well represented. As the war’s significant military action shifted to the outskirts of Atlanta and Richmond, Kentuckians during the Bramlette years were arguably more politically splintered, plagued by violence, and uncertain about what a looming postwar, postslavery future might mean than they were at any other time during the war.

Bramlette was one of the first men to leap to the defense of the old flag, even before Kentucky’s neutrality ended in the fall of 1861. He raised the Third Kentucky Infantry Regiment in the southern Kentucky counties surrounding his home, but Bramlette’s military career was not a lengthy one. He resigned in July 1862 to become a U.S. District Attorney.

Bramlette was elected during an election season dominated by debate over Kentucky’s role as a slave state and a loyal state. Dissatisfied in the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation, most white Kentuckians opposed the rebellion but neither were they enthusiastic about the federal war effort if it meant further erosion of slavery. Union Democrats searched desperately for a candidate after their first selection, Joshua F. Bell, withdrew his name after the nominating convention had met. Scrambling, the party chose Bramlette, who won in a bitter contest that saw some supporters of his opponent, former governor Charles Wickliffe, jailed by state and federal authorities for suspected Confederate sympathy.

Bramlette tried to strike a moderate tone that would play to both unhappy loyal masters and the Lincoln administration. Appealing to moderate antislavery men in the state, Bramlette encouraged Kentuckians to regard slavery as it was, a dying institution, and to plan for rebuilding the state on the basis of free labor. Attempting to assuage the anger of loyal masters who were urging resistance to the federal government’s antislavery policies, though, Bramlette also resisted any extension of civil rights to African Americans. Though it may seem odd that Bramlette simultaneously opposed slavery but resisted citizenship for African Americans, his position was quite common across the loyal states among people-Republicans and Democrats alike-who despised slavery as an institution yet also harbored deep, racially motivated mistrust of African Americans as individuals.

As principal intermediary between Kentucky and Washington, D.C., Bramlette had to balance the desires of loyal Kentucky slaveowners with the demands of the United States war effort. No other issue was so fraught with political peril as African American recruitment into the Union army. Initially, Bramlette and the state’s conservative proslavery leadership argued that allowing black men to serve in the army was the first step towards black citizenship, and mustered heated states rights rhetoric to defend Kentucky’s traditional purview over the state’s African American population. The Lincoln administration was not amused, and arrested a number of Bramlette’s political friends, including the Lieutenant Governor, R.T. Jacob. Yet, months later, when African American recruitment was an accomplished fact, the Bramlette administration cooperated with federal military authorities to claim credit for the service these black Kentuckians so that white men in the state would be exempted from the draft.

Bramlette had more to worry him than battles with Washington; during 1864 and 1865 Kentucky descended into chaos. Fueled by racialist resentment to the new freedoms asserted by African Americans and anti-government attitudes, bands of guerillas organized across the state. Some were nominally affiliated with the Confederate military, but most acted as law unto themselves, robbing and murdering their neighbors. Bramlette raised thousands of troops into state service to combat the guerillas, and while some saw success, most were ineffective. The worst of the state soldiers became partisan warlords themselves.

Bramlette oversaw both the end of the war and the end of slavery in Kentucky. Neither ended cleanly. Racial hostility and guerilla violence eventually coalesced into a proto-Ku Klux Klan reign of terror by the end of his term-prompting a massive exodus of black Kentuckians to states where personal safety and rewarding labor were easier found than at home. Though Bramlette himself seems to have genuinely mourned Lincoln’s death and admitted that the President had been right about the necessity of emancipation to end the war, white Kentuckians who dominated the legislature flatly refused to grant any civil rights to African Americans in the final years of Bramlette’s term. Though CWGK will only publish Bramlette’s papers through December 1865-when slavery was officially ended in Kentucky by the Thirteenth Amendment-his papers tell the fascinating story of a society whose foundations collapsed into a new-if perilous-birth of freedom.

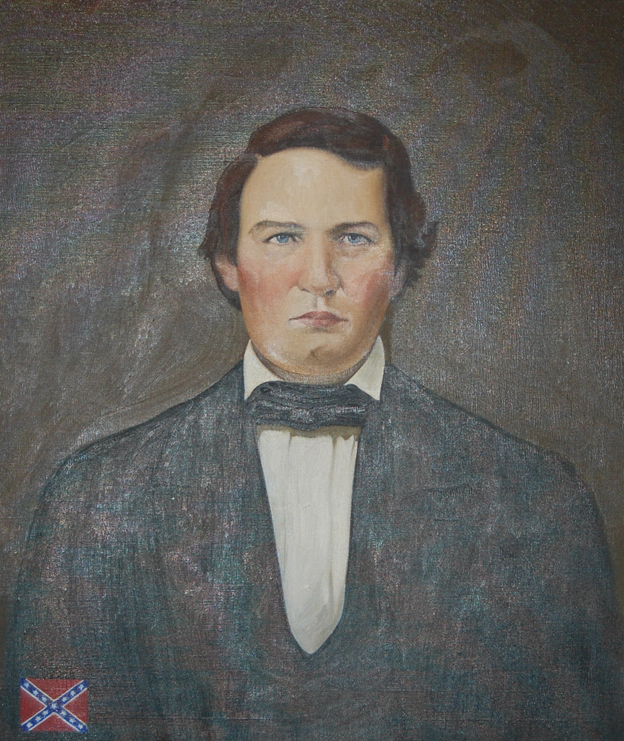

George Washington Johnson, 1861-62

Party: Democrat, Southern Rights.

Residence: Georgetown, Scott County.

Occupation: Lawyer and Planter

Fleeing home to set up a revolutionary government in exile, enlisting on the battlefield as a common soldier, and being mortally wounded only to be tended to in his dying days by friends in the Union army, George W. Johnson’s short term as Confederate provisional governor reads as much like a Romantic novel as it does history.

Johnson was a member of a wealthy and well-connected Bluegrass family whose members included U.S. Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson. In addition to investments in Kentucky farmland and the developing thoroughbred breeding and racing industry, the Johnsons and several other allied Kentucky families owned thousands of acres of cotton land in Mississippi and Arkansas. It is not surprising, then, that when the cotton-producing states of the Deep South seceded in the weeks following Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860 George Johnson ranked among the most enthusiastic supporters of Kentucky’s secession and admission to the new Confederacy.

Most white Kentuckians, though, were not so keen on the plan, and the state entered a period of neutrality, which ended with the state declaring full allegiance to the United States in September 1861. The Unionist legislature quickly passed laws condemning treasonous rhetoric and action, prompting Johnson and many prominent secessionists to flee the state. In late October, the secessionist exiles convened in a convention at Russellville, Kentucky, which was being occupied by rebel general and Johnson’s distant relative Albert Sidney Johnston. The Russellville Convention passed a secession resolution, established a provisional Confederate government for the state, declared Bowling Green the new capital, won admittance to the Confederacy, and elected George Johnson the state’s provisional governor in November 1861.

Johnson’s tenure in office was short lived. By February, Confederate defeats at Forts Henry and Donelson in West Tennessee and Mill Springs, Kentucky, forced the army and Johnson’s provisional state government to retreat south, conceding Bowling Green, Nashville, and nearly all of Tennessee. With little governing to do after the army left the state, Johnson volunteered as an aide on the staff of his cousin, Confederate General and former Vice President John C. Breckinridge, who commanded a brigade of rebel Kentuckians.

In early April, Albert Sidney Johnston finally turned to launch a counter-offensive near the Tennessee-Mississippi border. His April 6th attack on U.S. Grant’s Union army, encamped along the Tennessee River near Shiloh church, resulted in some of the war’s heaviest fighting in thick forested terrain. Still a volunteer aide, Governor Johnson rode with Breckinridge into the heart of the fighting that morning until stray federal bullets killed his horse. Eager to help the cause however he might, though, the governor enlisted as a private in one of Breckinridge’s regiments of Confederate Kentucky infantry. Fighting resumed on the 7th, though the death of General Johnston late in the first day and the arrival of Union reinforcements during the night turned the tide of battle against the rebels. As Breckinridge’s command fought to cover the Confederate retreat, George Johnson was grievously wounded and left on the field by his retreating comrades and constituents. Recognized by a friend and fellow delegate to the 1860 Democratic national convention, Union General Alexander McCook, Johnson was brought into the Union camp cared for as he died by loyal Kentuckians including James Jackson and John Marshall Harlan. After his death on April 8, these friends saw to it that his body was returned to Georgetown for burial.

Though he did little governing, Johnson’s fascinating personal papers allow CWGK researchers to access the wide-ranging and complex networks of business and family connections which knit the antebellum plantation elite together. More importantly, Johnson serves as a direct conduit linking the economic interests of the cotton South to the unique course of the secession crisis in Kentucky. In addition to his own role, Johnson’s close connections to so many principal players in Kentucky’s secessionist movement make his perspective on the first months of the war invaluable for researchers.

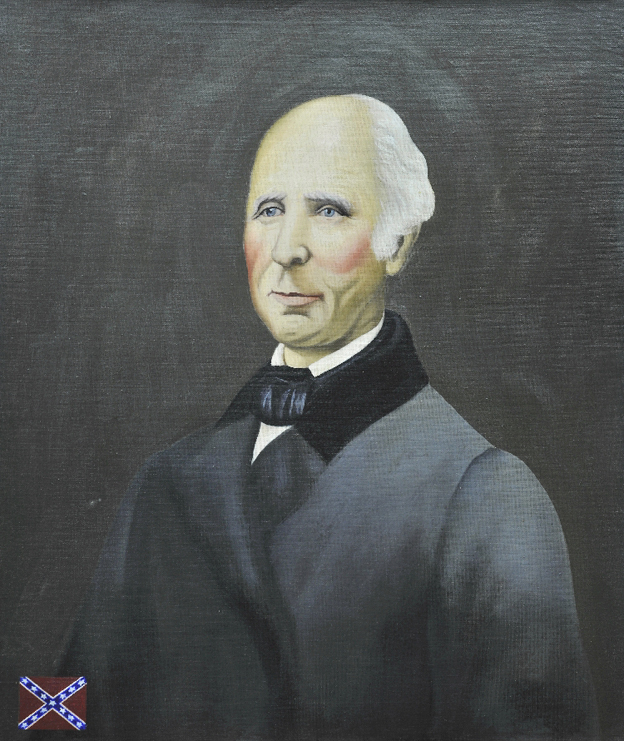

Richard Hawes, 1862-65

Party: Democrat, Southern Rights.

Residence: Paris, Bourbon County.

Occupation: Lawyer and Farmer

Confederate Provisional Governor Richard Hawes was at the center of one of the most dramatic moments in Kentucky history. In October 1862, with a Confederate army at his back, Hawes entered the Old State Capitol, was sworn in as governor, and gave a rousing inaugural address. The moment, though, was fleeting.

A generation older than Kentucky’s other Civil War-era governors, Hawes came to the Bluegrass from his native Virginia, living and working as a lawyer and part-time hemp planter in Lexington and Winchester before eventually locating to Paris, Kentucky. He began his political career as a Whig disciple of his distant relative, Henry Clay, eventually serving one term in Congress. After the Whigs collapsed under the weight of the issue of slavery in the early 1850s, though, Hawes found a new home in the Democratic party.

When the war came, Hawes fled to Virginia and took up a position as a Confederate staff officer. After George Johnson was elected the state’s first provisional governor, he requested that Hawes join him in Bowling Green, the new Confederate capital, to help administer the government. Hawes accepted, but took ill before he could play any active part. Compounding the crisis faced by the Confederate provisional government of Kentucky which had been forced to abandon the state in February, 1862, George Johnson’s death at the battle of Shiloh in April left the organization without an executive. According to the rules adopted by the secession convention at Russellville, it fell to a governing council of ten members-who were to assist Johnson until a new Confederate legislature could be elected and installed-to elect a replacement for the provisional governor if a vacancy should occur. Forbidden from choosing one of their own, the council elected Hawes.

Though the tide of war in the spring of 1862 had exiled the Confederate government under Johnson from Kentucky, a Confederate offensive that summer and fall afforded Hawes a chance to return and perhaps seize control of the entire state. When rebel armies drove virtually unopposed into Kentucky in August and September 1862, Hawes and the provisional government followed quickly behind. Disappointed by the unenthusiastic reception that the rebel troops received in Kentucky, Confederate commander Braxton Bragg hoped that a grand political gesture might lead the state to rise up against the United States. Veering off from an advance on the strategically important and poorly defended city of Louisville, Bragg marched on Frankfort to finally install Hawes at the legitimate seat of government.

In the midst of the ceremonies, Union artillery fired on the town, heralding the approach of a much larger force. The rebels abandoned Frankfort before the inaugural ball could be held. Less than a week later, a Confederate tactical victory at the battle of Perryville left rebel forces too weakened to continue operations in Kentucky. Hawes left Kentucky as Bragg’s forces fell back, never to return to Kentucky during the war. Hawes and the provisional government joined the refugee community of prominent Kentucky secessionists and their families, living with friends and family in the Confederacy. After time in Tennessee and Georgia, Hawes eventually returned to stay with family in Virginia, not far from Richmond where he could lobby Jefferson Davis and the Confederate government on behalf of rebel Kentucky soldiers, and the silent majority of sympathetic citizens whom they continued to believe-by and large erroneously-lay at home under Union occupation.

Returning to Kentucky in 1866, Hawes became a judge, issuing rulings that undermined the efforts of the Freedmen’s Bureau in the state, and was an active participant in Democratic politics until his death just over a decade later. Because he spent his term mostly out of state and frequently on the move, CWGK’s Hawes collections are thus far the smallest of any governors. What does survive, however, affords fascinating new access to the inner world Confederate national politics and of the thousands of refugee rebel Kentuckians. Hawes’s exile and wartime mobility requires that CWGK conduct exhaustive searches in the archives and libraries across the former-Confederate states to compile as broad a documentary base as possible.