Party: Democrat, Secessionist

Residence: Georgetown, Scott County

Occupation: Lawyer and Planter

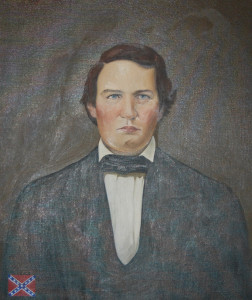

Fleeing home to set up a revolutionary government in exile, enlisting on the battlefield as a common soldier, and being mortally wounded only to be tended to in his dying days by friends in the Union army, George W. Johnson’s short term as Confederate provisional governor reads as much like a Romantic novel as it does history.

Johnson was a member of a wealthy and well-connected Bluegrass family whose members included U.S. Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson. In addition to investments in Kentucky farmland and the developing thoroughbred breeding and racing industry, the Johnsons and several other allied Kentucky families owned thousands of acres of cotton land in Mississippi and Arkansas. It is not surprising, then, that when the cotton-producing states of the Deep South seceded in the weeks following Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860 George Johnson ranked among the most enthusiastic supporters of Kentucky’s secession and admission to the new Confederacy.

Most white Kentuckians, though, were not so keen on the plan, and the state entered a period of neutrality, which ended with the state declaring full allegiance to the United States in September 1861. The Unionist legislature quickly passed laws condemning treasonous rhetoric and action, prompting Johnson and many prominent secessionists to flee the state. In late October, the secessionist exiles convened a convention at Russellville, Kentucky, which was being occupied by rebel general and Johnson’s distant relative Albert Sidney Johnston. The Russellville Convention passed a secession resolution, established a provisional Confederate government for the state, declared Bowling Green the new capital, won admittance to the Confederacy, and elected George Johnson the state’s provisional governor in November 1861.

Johnson’s tenure in office was short lived. By February, Confederate defeats at Forts Henry and Donelson in West Tennessee and Mill Springs, Kentucky, forced the army and Johnson’s provisional state government to retreat south, conceding Bowling Green, Nashville, and nearly all of Tennessee. With little governing to do after the army left the state, Johnson volunteered as an aide on the staff of his cousin, Confederate General and former Vice President John C. Breckinridge, who commanded a brigade of rebel Kentuckians.

In early April, Albert Sidney Johnston finally turned to launch a counter-offensive near the Tennessee-Mississippi border. His April 6th attack on U.S. Grant’s Union army, encamped along the Tennessee River near Shiloh church, resulted in some of the war’s heaviest fighting in thick forested terrain. Still a volunteer aide, Governor Johnson rode with Breckinridge into the heart of the fighting that morning until stray federal bullets killed his horse. Eager to help the cause however he might, though, the governor enlisted as a private in one of Breckinridge’s regiments of Confederate Kentucky infantry. Fighting resumed on the 7th, though the death of General Johnston late in the first day and the arrival of Union reinforcements during the night turned the tide of battle against the rebels. As Breckinridge’s command fought to cover the Confederate retreat, George Johnson was grievously wounded and left on the field by his retreating comrades and constituents. Recognized by a friend and fellow delegate to the 1860 Democratic national convention, Union General Alexander McCook, Johnson was brought into the Union camp cared for as he died by loyal Kentuckians including James Jackson and John Marshall Harlan. After his death on April 8, these friends saw to it that his body was returned to Georgetown for burial.

Though he did little governing, Johnson’s fascinating personal papers allow CWGK researchers to access the wide-ranging and complex networks of business and family connections which knit the antebellum plantation elite together. More importantly, Johnson serves as a direct conduit linking the economic interests of the cotton South to the unique course of the secession crisis in Kentucky. In addition to his own role, Johnson’s close connections to so many principal players in Kentucky’s secessionist movement make his perspective on the first months of the war invaluable for researchers.