That slavery and slaveholders often subjected the enslaved to sexual exploitation, coercion, and assault has been well documented by scholars and by ex-slave narrators like Harriet Jacobs and Louisa Picquet, both of whom endured unwanted sexual advances.[1] For at least two of slavery’s survivors, and probably countless more, the guerrilla conflict that engulfed Kentucky late in the Civil War also brought with it an additional danger of sexual violence. [2] Incomplete though they are, what follows are the stories of these two women—what they endured; how it was preserved in the historical record; and what that tells us about the politics of sex, race, gender, and the law on the cusp of slavery’s demise.

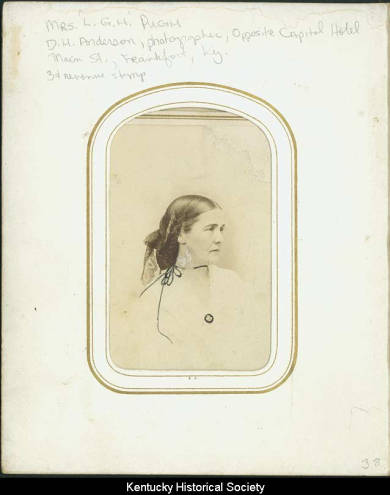

In November 1864, Hugh H. Martin, a Greenville farmer and avowed Unionist, wrote to Thomas Bramlette to “complain of the conduct of some of the men calling themselves State Guards.”[3] Eight to ten days earlier while a group of men under the command of Sebastian C. Vick commandeered a wagonload of corn from Martin’s property, one of the men “pursued and caught” a slave woman owned by Martin and “despite her resistance committed violence on her.” Since then, wrote Martin, the woman and her husband and been “greatly distressed and outraged, and I as their protector feel deeply injured.”[4] The identity of the woman is unknown, as Martin never names her in the letter. He mentions only that she was the wife of his favorite slave and that the couple had two children. The U.S. census shows that Martin owned four enslaved persons in 1860—three males ages 10, 18, and 36 and one woman who was 23 years old at the time.[5] But it is unclear if she is the same woman of whom Martin wrote. What is clear is the paternalism that permeates Martin’s account of sexual violence. Although he acknowledged that the woman and her husband felt “greatly distressed and outraged,” he also managed to make the assault, ultimately, about his perceived injury as a slaveholder. By styling himself as the couple’s “protector,” Martin conjured a favorite argument of slavery’s defenders that figured the relationship between master and slave as tantamount to that between parent and child. It portrayed bondspeople as perpetual children in need of protection and obscured the reality of slavery as a violent, exploitative institution in which the master benefitted from slaves’ expropriated labor. In reporting his own feelings of deep injury, Martin also gestured toward a feature of 19th century jurisprudence. In a case of sexual assault against a slave, an antebellum slaveowner might sue another white man for damages to his legal property, but the enslaved had no legal recourse; if the owner of the enslaved committed the assault, the law demanded no culpability.[6] The crime of rape against an adult slave did not exist until shortly before the Civil War, when an 1861 Georgia statute expanded the definition of rape to include victims both slave and free. [7] In Kentucky, the law defined rape specifically in terms of gender and race: “Whoever shall unlawfully and carnally know any white woman [emphasis added], against her will or consent, or by force, or whilst she is insensible, shall be guilty of rape.”[8] Not until February of 1866 could black or multiracial Kentuckians charge a white person with a crime, and then only by affidavit; they could be witnesses in criminal proceedings only against other African-Americans.[9] In a time and place where the law did not acknowledge sexual violence against African-Americans as a crime, the assault committed against the unnamed enslaved woman was ultimately recorded in the grievance registered by the man who owned her as property. Hugh Martin complained to the governor that he could not expect “protection or redress” from officers who could not keep their men in line, but at the time, if there had been any possibility of redress, it would have been Martin’s to seek, not that of the woman who had endured the assault.

Martin also felt compelled to assure the governor of his belief that the enslaved spouses were “faithful to one another.”[10] That Martin thought this detail material to the case betrays, if not his own acceptance, then at least an awareness of the derogatory stereotype of bondspeople as promiscuous. Specifically, Martin may have wanted to dispel the idea that the woman who was assaulted resembled in any way the cultural myth of the Jezebel, the unchaste African-American woman who was, according to Deborah Gray White, “the counterimage of the mid-nineteenth century ideal of the Victorian lady.”[11] A number of factors contributed to the myth of Jezebel in the minds of white Americans, including the fact that slavery left the bodies of female slaves exposed–whether due to ragged clothing, methods of punishment, or the intrusive examinations to which they were subjected on the auction block—and the concubinage often imposed by the men who owned them.[12] Even when the law seemed prepared to punish predation against enslaved children, it managed to reinforce the Jezebel stereotype. In Kentucky the “rape upon the body of an infant under the age of twelve years,” was punishable by death, and the statute did not specify the race of the victim.[13] But such a statute, even if used to prosecute the sexual abuse of an enslaved child–as Peter Bardaglio has argued about a Mississippi law that established the same age of consent–essentially codified the Jezebel myth into law by implying that slaves older than twelve could not be raped because they were, to borrow Bardaglio’s phrase, “incapable of withholding consent.”[14]

Within a few weeks of the assault in Greenville, a band of about twenty-five guerrillas carried out a robbery and murder spree in Washington County, leaving four men dead.[15] One of the leaders, Samuel O. Berry, was later tried for his guerrilla activities by a U.S. military commission. The charges included fourteen murders, six counts of robbery, and two counts of rape. The trial was held in Louisville and covered extensively by the Daily Courier, which published a daily transcript of the testimony. Among the prosecution witnesses was a Nelson County freedwoman named Laura, who testified that she had been raped by Berry at gunpoint. “I cried and begged him not to,” Laura told the prosecutor, “but he would do it; he had his pistol drawn on me all the time.” Asked if she was a free woman at the time of the assault, Laura answered, “Well, I supposed I was what was called ‘free’; I had a husband in the army.” Her response seemingly hinted at a disparity between the legal qualification of freedom and the reality of Laura’s living situation at the time, but it was also essential to her ability to testify. Before he began his cross-examination, Berry’s attorney moved to have Laura’s testimony excluded because of her color and on the grounds that she had been a slave at the time of the assault. Implicit in his motion was the abhorrent suggestion that these two factors somehow rendered the violence against Laura insignificant, that her color and her enslaved status negated her right to seek legal redress against her rapist. And that might have been the case but for the one critical factor that her husband was in the army. Legally, this made her a free woman at the time of the assault. Her testimony would stand.[16]

On cross-examination, the defense asked all manner of intrusive and degrading questions in an attempt to blame and discredit the witness. Why hadn’t she run away or called for help? “I was afraid to,” replied Laura, who testified that her child was also upstairs in the house where the rape occurred and that Berry held a pistol the whole time. The defendant, who reportedly lost his hand above the wrist in an industrial accident before the war, was widely known as “One-Armed Berry.”[17] Throughout the trial, as the attorney for the defense attempted to challenge witness identifications of Berry, his efforts were undermined when people who did not know Berry personally, cited this distinguishing feature as the means by which they recognized him during the commission of various crimes. In cross-examining Laura, the defense tried to use this disability—which had not seemed to interfere with Berry’s marauding—as a way to cast doubt on her testimony. “How could he ravish you if he kept his pistol in his hand all the time?” the attorney asked. Laura’s terse and matter-of-fact reply suggests she was unflappable: “Well, he did it.” “I want to know how he did it,” the attorney persisted. Again, Laura stated, “He ravished me with his pistol in his hand.” The attorney turned to another line of questioning: “Did this party that went up stairs with you offer you any money?” In the exchange that followed, Laura revealed that the assailant had given her a quarter “after he got through and [was] just ready to come downstairs.”[18] Though he did not say as much directly, the implication of the defense’s question was that the monetary transaction had rendered the incident an act of prostitution for which Laura was financially compensated. But Laura stated repeatedly throughout her testimony that her assailant had held a gun and that fear prevented her from running away or calling for help. No wonder she did not refuse the coin, as that act might have provoked the rapist to shoot Laura or harm her child.

Berry was found guilty of being a guerrilla and of the various specifications of robbery, rape, and murder. He received a sentence of death, but this was later commuted to ten years in prison.[19] That Laura’s status as a free woman and, thus, the admission of her testimony hinged on her marriage to a U.S. soldier highlights the reality that emancipation and the citizenship rights of freedpeople rested largely on the military service of African-American men. Laura was able to tell her story and to speak for herself in the public record. Still, it was her relationship to her husband that made that possible. Laura’s case can hardly be read as a sweeping victory for the formerly enslaved who endured sexual exploitation and assault in slavery. It seems unlikely that the rape would have been prosecuted had it not been one in a litany of charges brought in a U.S. military court against an infamous guerrilla leader. But in a justice system that was more apt to treat victims like the anonymous enslaved woman owned by Hugh H. Martin, it was a notable, if rare, instance in which a survivor had her day in court.

Christina K. Adkins has a PhD in American Studies. Her work focuses on slavery and cultural memory.

___________________________________________________________________

[1] Harriet Jacobs, 1861, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Documenting the American South, University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2003, https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/jacobs/jacobs.html; Louisa Picquet,1861, Louisa Picquet, the Octoroon: or Inside Views of Southern Domestic Life, Documenting the American South, University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2003, https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/picquet/picquet.html.

[2] On guerrilla war in Kentucky, see especially Daniel Sutherland, A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009) 220-25.

[3] Martin and at least one other correspondent, W. H. Faris, questioned whether Vick and his men had the governor’s approval to operate as members of the State Guard. Faris reported to the governor that Vick had been “acting out the most complete military force that has come to pass during this war” and warned Bramlette that if Vick and his men were allowed to continue a controversial policy of impressment, they would grow bolder and “a vast amount of civil injuries…will grow out of this thing,” W. H. Faris to Thomas E. Bramlette, 10 August 1864, Guerilla Letters, Document Box 1, Folder G. L. 1864, Kentucky Department of Military Affairs, Frankfort, KY. Accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0002-225-0052

[4] H. H. Martin to Thomas E. Bramlette, 11 November 1864, Guerilla Letters, Document Box 1, Folder G. L. 1864, Kentucky Department of Military Affairs, Frankfort, KY. Accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0002-225-0059.

[5] Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Slave Schedules, Kentucky, Muhlenberg County, District 1, p. 8.

[6] Peter W. Bardaglio, Reconstructing the Household: Families, Sex, And the Law in the Nineteenth-Century South, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 66.

[7] Peter W. Bardaglio, Reconstructing the Household: Families, Sex, And the Law in the Nineteenth-Century South, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 68.

[8] Richard Stanton, Revised Statutes of Kentucky, Approved and Adopted By the General Assembly, 1851 And 1852, And In Force From July 1, 1852, vol. 1 (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1867) 379-80.

[9] Harvey Meyers, ed., A Digest of the General Laws of Kentucky: Enacted by the Legislature, Between the Fourth Day of December, 1859, And the Fourth Day of June, 1865: Embracing the General Laws Passed Since the Publication of Stanton’s Edition of the Revised Statutes : With Notes of the Decisions of the Court of Appeals of Kentucky : With an Appendix Containing the Laws of the Winter Session, 1865-’66 (Cincinnati: R. Clarke, 1866), 735-36.

[10] H. H. Martin to Thomas E. Bramlette, 11 November 1864, Guerilla Letters, Document Box 1, Folder G. L. 1864, Kentucky Department of Military Affairs, Frankfort, KY. Accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0002-225-0059.

[11] Deborah Gray White, Ar’n’t I a Woman: Female Slaves in the Plantation South, rev. ed. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1999), 29.

[12] White, Ar’n’t I a Woman, 31-34.

[13] Stanton, Revised Statutes, 379.

[14] Bardaglio, Reconstructing the Household, 68.

[15] Richard J. Browne to Thomas E. Bramlette, 29 November 1864, Guerilla Letters, Document Box 1, Folder G. L. 1864, Kentucky Department of Military Affairs, Frankfort, KY. Accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0002-225-0060

[16] William L. Myers and Albert E. Cochran, “Trial of One-Armed Berry, the Guerrilla: Second Day’s Proceedings,” The Louisville Daily Journal (Louisville, Ky.), Jan 17, 1866, p. 1.

[17] “Sam Berry’s Lost Arm,” Louisville Daily Courier, (Louisville, Ky.), January 26, 1866, p. 3.

[18] Myers and Cochran, “Trial of One-Armed Berry,” 1.

[19] The Papers of Andrew Johnson, vol. 10, February- July 1866, ed., Paul H. Bergeron (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992), 249.