The Caroline Chronicles:

A Story of Race, Urban Slavery, and Infanticide in the Border South

“Part I: Incidents in the Life of a Contraband”

By Matthew C. Hulbert

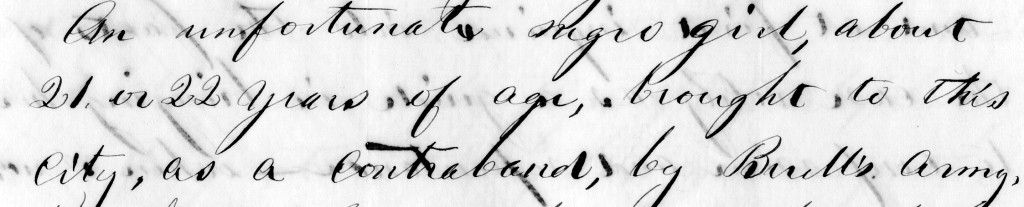

Early in the fall of 1862, an African American woman named Caroline Dennant arrived in Louisville. This wasn’t a happy homecoming, for she had no family in the city. Nor was it the endpoint of a successful escape from bondage. Because despite its official pro-Union position, Kentucky remained a slave state that would honor its obligations to the Fugitive Slave Law if at all possible. So at approximately twenty years old, she’d come in with General Don Carlos Buell’s army, from Tennessee, not as a newly-made freeperson, but as contraband. She was homeless, completely alone, and without a penny in her pocket. Even Caroline’s surname had been borrowed from the planter who still technically owned her—and who could, at any moment, arrive in Louisville to claim her as one might any other piece of lost property.

In the meantime, Caroline was arrested as a fugitive slave and sent to live in the home of Willis Levy, a river freighter, his wife, Annie, and the couple’s toddling daughter, Blanche. According to Caroline, “for this kindness she was grateful” and “she endeavored to pay for this kindness by being attentive to her duties as a servant … watchful of their interest & in all things to be faithful and trustworthy.” Her duties included cooking for the family, cleaning their small one-story house in a working class Louisville neighborhood, and serving as a nanny for Blanche. As noted by onlookers, Caroline was “a good servant & seemed to love the child … [she] was very fond of Blanche.”

In the meantime, Caroline was arrested as a fugitive slave and sent to live in the home of Willis Levy, a river freighter, his wife, Annie, and the couple’s toddling daughter, Blanche. According to Caroline, “for this kindness she was grateful” and “she endeavored to pay for this kindness by being attentive to her duties as a servant … watchful of their interest & in all things to be faithful and trustworthy.” Her duties included cooking for the family, cleaning their small one-story house in a working class Louisville neighborhood, and serving as a nanny for Blanche. As noted by onlookers, Caroline was “a good servant & seemed to love the child … [she] was very fond of Blanche.”

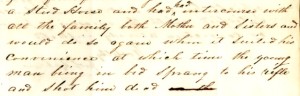

Days turned into weeks, weeks turned into months. Caroline’s former master never appeared to drag her back to the plantation. She met, and apparently married, another contraband slave who lived across the street with the family of Raymond Lynch. Lynch had married Annie Levy’s sister and, owing to proximity and familial ties, Caroline’s husband was typically allowed to spend nights with her at the Levy house. Though still a servant—and still trapped in fugitive limbo—it looked as though Caroline had left the worst of slavery behind in Confederate Tennessee. That is, until everything changed in February 1863.

***

Willis Levy was not a well-liked man. In fact, for reasons that will soon become obvious to animal-lovers, he was more or less despised by all of his neighbors and extended family. Luckily for Caroline, work kept him away from home for months at a time—but even this proved not to be long enough. In December 1862, Levy “purchased strychnine for the purpose of killing some cats and pigeons that had been annoying him.” As Caroline watched in the kitchen, he applied the poison to small cubes of beef, even remarking that he’d used enough to “kill a regiment of men,” before throwing the toxic bait under the homes of his neighbors, unbeknownst to them and without their permission. Then Levy poisoned grains of wheat and left them in a tin can in the backyard to attract and kill birds. When he was through, Caroline watched Levy’s wife put the container of poison back in a small, unlocked trunk in the kitchen.

In subsequent weeks, tension rose and the “honeymoon period” seemed to end; Willis and Caroline clashed repeatedly. In one instance, he blamed her for leaving a gate open. As a result, a cow had wandered into the yard and destroyed several small fruit trees. Another time, Caroline threw kitchen trash onto a fence just a few hours after Willis had finished whitewashing it. In the latter case, he reportedly told her “for two cents he would give her a thousand lashes.” The morning following the fence debacle, Willis left for a boat trip to Tennessee. During his absence, Annie Levy also took issue with Caroline’s behavior, this time for wasting candles by staying up late in the evening with her husband.

A few days later, Annie arrived home from a walk with her sister and noticed that a trunk in the kitchen had been moved from its usual spot. She questioned Caroline, who immediately denied having disturbed or opened the trunk. That evening, Annie didn’t sleep well; she “awoke several times during the night & on one occasion had a singularly strangling or suffocating sensation about the lower part of the throat.” Due to her sickness, Annie and Blanche came down late for breakfast, whereupon the former was surprised to find that Caroline had poured her a cup of coffee. The presence of coffee wasn’t in itself unusual. She drank coffee every morning—but this was the first time in the entirely of Caroline’s tenure with the family that she’d poured it for her mistress. Almost immediately, Annie noticed something different about the taste of the coffee but chalked it up to her restless night. Shortly thereafter, she retired for a nap, leaving Blanche in Caroline’s care.

Not long after Annie Levy laid down, Caroline came into the room and said “Miss Anne come out & see Blanche she acts so strangly [sic].” The pair rushed outside to find the toddler “lying on the ground in convulsions … about three feet from the kitchen door.” According to court documents, “the child frothed at the mouth, became livid under the eyes, around the lips & about the finger nails & on the feet.” Blanche died quickly—and “professional men,” likely a mix of doctors and policemen, determined that she’d been killed by a fatal dose of strychnine. An autopsy was performed in which Blanche Levy’s stomach was “bottled, sealed up & carried by two persons to an experienced practical chemist.” The contents of the stomach were analyzed; all tests pointed to strychnine ingestion and accompanying asphyxiation. For final verification, the chemist even fed a bit of the stomach contents to a frog. It died immediately while exhibiting symptoms of strychnine poisoning.

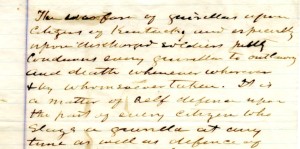

Caroline was charged with murder. At first glance, the pieces seemed to fit together. She’d watched Willis Levy use strychnine before and at least vaguely understood what doses would kill animals of different sizes. She knew where he kept the poison and had easy access to it. This was all circumstantial evidence, to be sure, but black men and women in slave states had been found guilty under far less precarious circumstances. Moreover, her recent clashes with both Willis and Annie Levy constituted clear enough motive for an all-white jury hell-bent on avenging the death of a white child. Within the span of a few months, Caroline Dennant was convicted of infanticide and sentenced to hang from the neck until dead. Her execution was scheduled for the morning of September 11, 1863, roughly one year to the day since she trudged into the city with Buell’s men.

***

This opening salvo of The Chronicles of Caroline represents just the first installment of several to come, penned by myself or fellow CWG-K editor Patrick Lewis. In the coming weeks, we will not only reveal Caroline’s fate as a date with the hangman loomed—we’ll also add contextual commentary. These future installments will address both sides of Caroline’s legal case in deeper detail (that is, we will analyze the cases for and against her); the broader logistics of contraband hiring and fugitive slave keeping in urban settings like Louisville; white-led abolition movements in Kentucky and the social networks that spearheaded them on behalf of fugitives like Caroline Dennant; and, how Caroline’s story—whether she was guilty or not—fits within a much wider, interconnected corpus of academic scholarship and popular mythology concerning slave resistance and rebellion in both the antebellum and the wartime South.

Matthew C. Hulbert is an Assistant Editor of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.

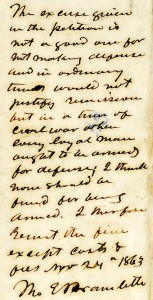

SOURCES: Affidavit of Mrs. Josephine Lynch, 17 September 1863, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY (hereafter KDLA); Caroline Dennant to Thomas E. Bramlette, KDLA; J. G. Barrett to Thomas E. Bramlette, 2 September 1863, KDLA; Affidavit of Raymond Lynch, 19 September 1863, KDLA; Testimony in the Case of Commonwealth of Kentucky v. Caroline (a slave), KDLA; John L. McKee to Thomas E. Bramlette, 3 September 1863, KDLA.