The Caroline Chronicles:

A Story of Race, Urban Slavery, and Infanticide in the Border South

“Part V – The Husband”

By Patrick A. Lewis

Once during Levi’s absence Mrs Levi reprimanded Caroline & her husband (a contraband who hired to Levi’s brother but slept at Willis Levi’s with his wife evry night) that they must not site up so late & keep a light burning

This passage has always been a frustrating one. In 6,500 words of documentary evidence about Caroline, her husband is only ever mentioned in this passage. Who was he? Did they run away together from Tennessee? Did she meet him on the road to Kentucky or in the streets of Louisville?

And, spoiler alert, I can’t answer any of those questions. But after looking for answers, we have a new appreciation for the bigger implications of Caroline’s story.

Let’s deconstruct that sentence. Who was “Levi’s brother”? The Willis Levi in whose home Caroline was a domestic servant was, in fact, Willis Levi, Jr. His namesake and father, a Virginia native, co-owned a “sale and exchange stable” that hired and sold horses and carriages on Market Street with an elder son, Elias Levi. There are other Levi brothers besides Elias in the picture, too. A 36-year-old Mordecai (in the family business of horse trading) and a 35-year-old James Levi (in the fascinating profession of lightning rod maker) live next door to the Levi patriarch in 1860.

So, knowing there were a number of potential Levi brothers to whom Caroline’s husband might hire, I went to the Jefferson County Court Minute Book to see what official county records might reveal. Elias was the only Levi who appeared on the record in 1862 and 1863. What was he up to?

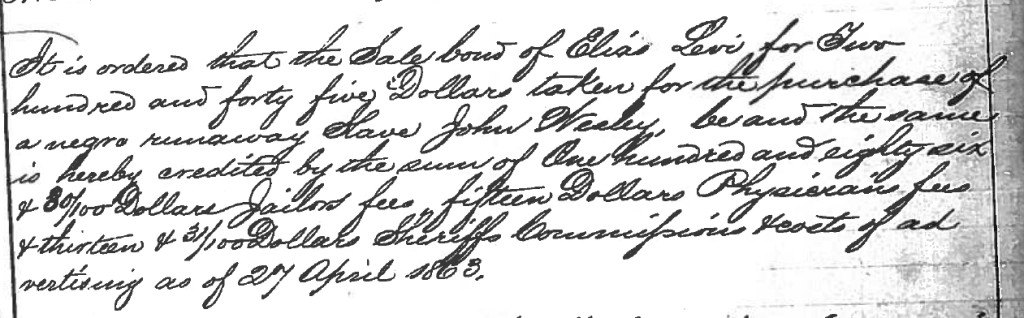

Monday May 4th 1863.

It is ordered that the Sale bond of Elias Levi for Two hundred and forty five Dollars taken for the purchase of a negro runaway Slave John Wesley, be and the same is hereby credited by the sum of One Hundred and eighty six & 30/100 Dollars Jailors fees, fifteen Dollars Physicians fees & thirteen & 31/100 Dollars Sheriffs Commission & costs of advertising as of 27 April 1863.

He is buying fugitive slaves from the sheriff of Jefferson County. Under Kentucky law, a sheriff was required to publicly advertise the capture of a fugitive and, if the owner did not come forward, to sell the fugitive to recoup the state’s expenses. Following that process, Elias Levi bid on and won John Wesley, “about 25 years of age, 5 feet 6 inches high, weighing 145 lbs; thin whiskers and mustache; round face and high forehead,” and Mary, who was not among the 18 people advertised in the Louisville Journal but was on a list of 29 people in the County Court minutes sold by the sheriff that day.

Could John Wesley be Caroline’s husband? Maybe. Of course, the testimony we have says that her husband hired to Levi’s brother, not was a slave of. But, then again, that testimony concerned events in February 1863, at which time we can say with certainty that Elias Levi did not own John Wesley (even if he may have controlled or coerced his labor under some other arrangement). And, frankly, without some new information we’ll never be able to know.

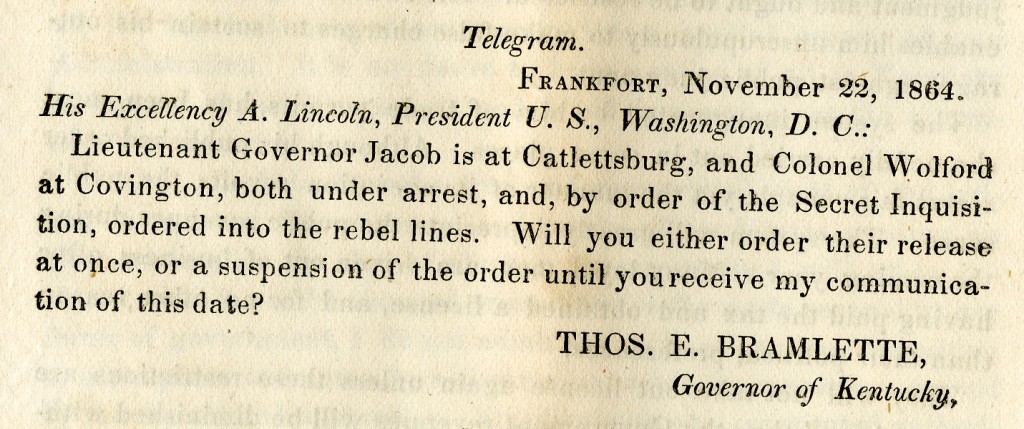

The (maybe) good news for John Wesley is that he was not the slave of Elias Levi for very long thanks to the United States Army. The day after Levi’s bond was entered, the County Court demanded to know why Captain Matthew H. Jouett “took from the custody of the Sheriff the runaways” sold on the block alongside John Wesley. Jouett punted up his chain of command to the Provost Marshall of Louisville, Colonel Marcellus Mundy, who had ordered the sales of fugitives in Louisville invalidated. Mundy had, to put it mildly, no especial regard for African American refugees in Louisville. In fact, he had complained directly to Lincoln about emancipation policy, pleading that Unionist Kentuckians—”masters for loyalty’s sake“—should be exempt from the hard hand of war.

Fortunately—and probably because of sentiments like the above—Mundy was being watched closely. Word of the sale in which Elias Levi had purchased John Wesley and Mary had reached Washington, prompting President Lincoln to clarify his Emancipation Proclamation and the Second Confiscation Act for any Kentuckians who—like Mundy, the sheriff, and Elias Levi—thought freedom didn’t follow individual refugees from the Confederacy when they entered the loyal slave state of Kentucky.

The President directs me to say to you that he is much surprised to find that persons who are free, under his proclamation, have been suffered to be sold under any pretense whatever; and also desires me to remind you of the terms of the acts of Congress, by which the fugitive negroes of rebel owners taking refuge within our lines are declared to be “captives of war.” He desires you to take immediate measures to prevent any persons who, by act of Congress, are entitled to protection from the Government as “captives of war” from being returned to bondage or suffering any wrong prohibited by that act. (OR series 1, volume 23, pt. 2, p. 291)

John Wesley and Mary weren’t sold, but were they subsequently freed? If so, where did they go after the army intervened to stop their sale to Elias Levi? Unfortunately, these are the same unanswered questions we have for Caroline after Governor Bramlette pardoned her in September 1863.

What we can say, though, is that executing Kentucky’s fugitive slave laws was profitable for sheriffs, local governments, and would-be slaveowners looking to purchase cheaply when supply was high, that the first waves of emancipation were a boon to the economies of slavery in Louisville and surrounding counties. As thousands of African Americans like Caroline and John Wesley escaped slavery in Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi, they made perfect targets for reenslavement schemes run by law enforcement and local slave traders. Those individuals and institutions exploited the uncertainty about contrabands, confiscation, emancipation, and freedom in the fall of 1862 and spring of 1863 to flood Kentucky slave markets with Deep South slaves at bargain prices—this after Kentucky had been a net slave exporter to the cotton plantations of the Old Southwest for a generation. The very months when most Americans believe the Emancipation Proclamation freed tens of thousands of slaves proved to be the greatest slave market bonanza in Kentucky history.

While we can look ahead and see Caroline and John Wesley as the harbingers of emancipation in Kentucky, it may not have looked like that to Kentucky masters—and it certainly didn’t look like that to them.

Patrick A. Lewis is Project Director of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.