JURY, n. A number of persons appointed by a court to assist the attorneys in preventing law from degenerating into justice. – Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary

***

By Matthew C. Hulbert

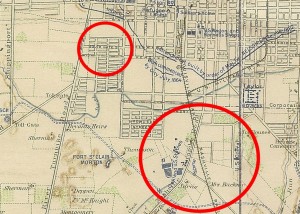

In July 1863, a Gallatin County man named Frank Story overpowered Jane Kelly, a local white woman. (This racial distinction is important because had Kelly been African American, a trial record would probably not exist.) He abducted his victim with one purpose in mind: “to have carnal knowledge with her.” Details are few and far between of the attack itself—but we do know that Story’s advances were unwanted (hence the abduction) and that he failed to complete his above stated purpose before being interrupted by multiple witnesses, who turned out to be children. A Grand Jury swiftly convened in Gallatin County and indicted Story for attempted rape (read the full document in Early Access). Not long after, a trial jury convicted him of a lesser charge; rather than attempted rape, these jurors found Story guilty of assault and battery and sentenced him to a measly four months in prison and a $100 fine.

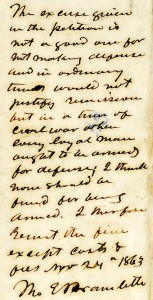

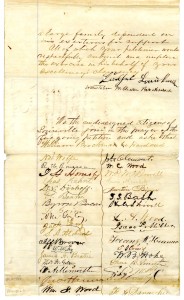

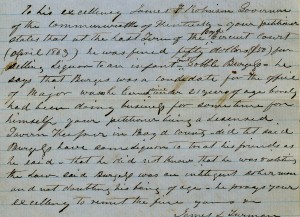

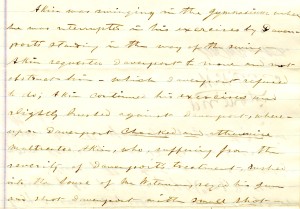

Oftentimes we find examples in the CWG-K archive wherein a trial jury is compelled for one reason or another to produce a certain verdict and then immediately requests that the governor use his executive power to override the original decision. Put another way, the jury does what they feel the letter of the law obligated them to do before turning to the chief executive of the Commonwealth to ensure that justice is meted out. (The same jurors convicting Caroline Dennant of infanticide and then requesting her pardon is one such illustration.) In this case, a petition was sent to Governor Thomas Bramlette; it was signed by all twelve of the jurors who convicted Story along with the sheriff of Gallatin County, the attorney who prosecuted the case, and numerous other officeholders and private citizens. Given that Story’s sentence seems so short and the nature of his transgression so violent; contemporary readers might jump to the conclusion that the jurors were compelled to lessen his charges on a legal technicality. They might also assume that the governor, Thomas Bramlette—himself a former judge with a fire and brimstone reputation—will set things right based on the petition. Unfortunately for Jane Kelly, those assumptions would be wrong. The petitioners actually believed that her attempted rapist had been the party robbed of justice.

According to the petition, which was spearheaded by Thomas Ritchey, the trial jury refused to convict Story of attempted rape based on the testimony of children—despite the fact that the Grand Jury had used the same testimony to indict. Moreover, the men writing on Story’s behalf believed Bramlette should grant a full pardon because 1) Story was only fifteen years old at the time of the crime; and, 2) because his father had been away in the Union army and as a result “had not that Control over his Son & could not govern his conduct as he would like to have done.” In other words, at fifteen years of age, Frank Story could not be expected to control himself in the manner of an adult and thus should not have been held responsible for attempting to rape Jane Kelly.

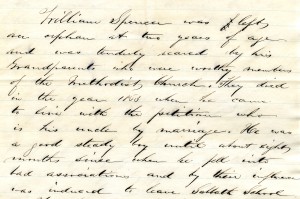

As past readers of the CWG-K blog will note, the law in Kentucky generally failed to take a consistent stance on the convicting and sentencing of minors. For instance, William Spencer, himself fifteen years old, was initially sentenced to 3.5 years in the state pen for stealing a pair of used trousers before having the punishment commuted to one month. Also recall the case of Graham Akin, a fourteen year old from Danville who was convicted of attempted homicide but only fined $50. So, it really should not surprise anyone that Kentuckians in 1863-64 tried to use Frank Story’s age to get him out of an already truncated prison sentence. Nor should it stun you to learn that Thomas Bramlette did, in fact, exercise clemency—freeing Story halfway through his prison term and remitting the $100 fine.

Kentucky’s legal system in the 1860s had little idea how to define childhood and thus struggled mightily to sentence minors. That much has been established already. The more revealing line of inquiry raised by the Story-Lane encounter has to do with the way male jurors and court officers reconciled their own conceptions of self-honor with gender, age, and the weight of one’s word. Unlike in the aforementioned case of William Spencer—who was convicted based on the testimony of an adult male victim/witness and received a relatively harsh sentence—the main witnesses against Frank Story were a mix of minor and adult, but neither was the magic combination of adult male. So on one hand, the jurors in The Commonwealth vs. Frank Story would have been willing to punish children as adults under certain circumstances, while not considering the testimony of children on equal terms with that of an adult (even when the defendant himself was a child).

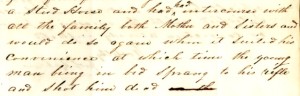

What jumps out here is that the testimony of Jane Kelly hadn’t mattered from the start. The petition specifically stated that, “His [Story’s] guilt was proven by children only” (my emphasis). This wasn’t a case of accidental oversight—it’s where the honor component comes into the story. Despite her being both an adult and a firsthand witness to the crime, Kelly’s word wasn’t valued enough to land a full conviction. Not because male jurors believed she was untrustworthy—because a female voice was never supposed to be an integral part of the process at all.

In 1850s and 1860s, southern men liked to believe their lives were structured around a paternalistic, hyper-masculine code of honor in which dependents—women and children—required their protection. At the same time, within the gendered confines of this system those same women were not considered competent enough as witnesses to describe to their would-be protectors from what or from whom they actually required defense. Therein, at least in theory, women were fundamentally no different than their children. With this in mind, Jane Kelly was only supposed to play the role of damsel in distress and then of grateful ward. But the logistics of the crime and subsequent trial didn’t work out that way. No men could take the stand to testify, so it was either a woman or children whose voices would have to be lent authority in court. Faced with this decision, the jurors begrudgingly chose to prioritize the children’s testimony, which kept Jane Kelly in her proper role.

What this hiccup in the system ultimately confirms is that the “code of honor” undergirding it was never actually based on protecting dependents. It was designed to appear that way to advance a patriarchal agenda. As such, it was laden with loopholes designed to give men a way to protect themselves and their status/authority first, even at the expense of a sexual assault victim like Jane Kelly.

Matthew C. Hulbert is an Assistant Editor of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.

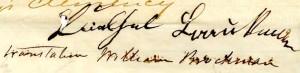

All of which your petitioner would respectfully submit and implore the exercise in his behalf of your Excellency’s clemency

All of which your petitioner would respectfully submit and implore the exercise in his behalf of your Excellency’s clemency

“All of which your petitioner would respectfully submit and implore the exercise in his behalf of your Excellency’s clemency

“All of which your petitioner would respectfully submit and implore the exercise in his behalf of your Excellency’s clemency

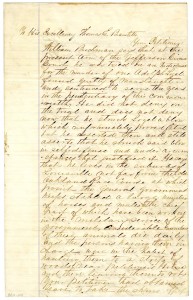

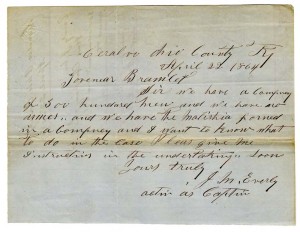

Jesse M. Everly, the author of this letter now housed at the

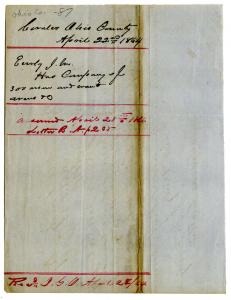

Jesse M. Everly, the author of this letter now housed at the  On the reverse of Everly’s note is the clerk’s annotation when this letter was received and filed in Frankfort—in the very arsenal building where this document is housed today. By this time in the war, military filing procedures were standardized and predictable. The clerk (in order, down the page) noted the date and place of the letter, recorded the author and a brief summary, listed the date of response and the book where the outgoing letter was copied, and logged the date of reception at the office.

On the reverse of Everly’s note is the clerk’s annotation when this letter was received and filed in Frankfort—in the very arsenal building where this document is housed today. By this time in the war, military filing procedures were standardized and predictable. The clerk (in order, down the page) noted the date and place of the letter, recorded the author and a brief summary, listed the date of response and the book where the outgoing letter was copied, and logged the date of reception at the office.