By Matthew C. Hulbert

In January 1864, a court-martial convened in Lexington, Kentucky, to decide the fate of Charles Helton. As Second Lieutenant of Company I, 39th Regiment, Kentucky Volunteer Mounted Infantry (U.S.A.), Helton and the men he commanded had an inherent duty to protect civilians from all manner of Confederate assault. The events of December 14, 1863, however, underscored the extent to which those civilians often needed guarding from the very men supposedly paid to protect them.

According to court documents, on the aforementioned December 14, 1863, Helton went to the house of Thomas Russell, himself a Union officer (a captain of the 45th Kentucky Volunteer Infantry) and “did in a rude and ungentlemanly manner use threatening and insulting Language to the wife and daughter of Capt Thos Russell.” More startlingly, Helton also tried to persuade Russell’s daughter to “accompany him from the house” and, when the young girl refused, he drew his pistol and shouted “By god you shall go or I will kill you.” The victim, whose first name was not revealed in the proceedings, successfully fled from the scene and escaped Helton’s ultimatum. For this incident, he was charged with “conduct unbecoming an officer and gentleman,” though attempted kidnapping with the intent to commit rape might have been more appropriate given how the rest of the day would unfold…

Stung by his failure to lure off the young Miss Russell, Helton next went to the home of Emanuel Spence. There, he again hurled “insulting Language” and managed to fire his pistol in the house (fortunately not wounding anyone). Once more, he attempted to abscond with a female captive; having already displayed a willingness to use his gun, Helton employed “threats” of violence to “compel Mrs Zelphina Spence to accompany him one-fourth of a mile from her house, attempting to persuade her to go to camp with him, there to be as a wife to him.” She declined the invitation—and also managed to get away from Helton unharmed. This episode was added as a second specification to the “conduct unbecoming” charge.

Now smarting from two [un]romantic rejections, a more desperate (and almost certainly more inebriated) Helton returned to the Russell house and commenced to “rudely assault the wife of said Capt Russell.” Helton declared that he would “stay all night with her,” to which Mrs. Russell responded by telling him to leave. Not to be deterred, Helton replied emphatically, “By god. I will stay,” at which point Mrs. Russell wisely “ran into another room, and shut the door.” From there, the situation quickly turned violent.

Said Helton kicked the door violently, and said to her, “If you do not open the door, I will blow your God damned brains out,” and forced the door open, and followed said Mrs. Russell into another room; and caught hold of her and tore her dress open and thrust his hand into her bosom, saying, I have been on a scout fourteen days, and by God I must have you for my purposes now, and the said Helton did, by force, attempt to throw said Mrs. Russell on the bed.

As noted in court testimony, only the “timely appearance of two countrymen” stopped the assault and spared Mrs. Russell. For his final assault of the day, Helton was charged with “assault and battery with intent to commit rape.”

With regard to assault and battery, attempted rape, and conduct unbecoming, Helton plead guilty and was found as such on each charge. More curiously, he was not guilty of “drunkenness on duty,” despite the fact that liquor had clearly helped fuel his daylong “rampage” through Rock Castle, a community near the Kentucky-West Virginia border. The decision seems doubly odd in light of evidence showing that while on a scouting mission on the very morning of the day the assaults took place, Helton was deemed “intoxicated to such an extent that he was unable to command, and did permit his company to become demoralized and scattered in consequence of said intoxication.”

In addition to being stripped of his rank and pay, Helton was sentenced to three years of hard labor “with ball and chain attached to his leg.” At the end of his prison term, he was to be dishonorably discharged from the Union military. To modern eyes, Helton’s sentence appears rather light for an attempted rapist running around drunkenly with a gun—and even lighter for one essentially guilty three times over on the same day. But in 1864, three years of hard labor was a relatively harsh punishment for Helton’s crimes. In fact, the archives of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition are replete with cases of attempted rape and rape being downplayed, if not outright excused or justified, by male judges, lawyers, and jurors.

With this in mind, what probably provoked the firm sentence had less to do with justice for Mrs. Russell or Helton’s other female victims than it did with preserving support for the Union cause among civilians. In many parts of the state, the relationship between the Union government and civilians who wanted to remain in the Union but also to protect slavery was already rocky—and the military could scarcely afford to concede its ability to protect them from Confederate invaders or neighborhood bushwhackers, let alone from its own soldiers. Nor, for that matter, could it concede that civilians might be safer joining the ranks of the irregular war than relying on regular troops for protection.

In any case, as this story makes clear, we would be wise to remember that while Kentucky’s Civil War homefront was fraught with hazards—especially sexual ones for women—the danger didn’t always stem from contact with “the enemy” as we typically like to imagine him.

Matthew C. Hulbert is an Assistant Editor of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.

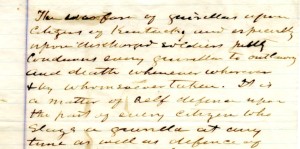

SOURCE: “General Orders No. 89,” Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, Kentucky.