by Matthew C. Hulbert

On November 18, 1861, a three-day convention kicked off in Russellville, Kentucky. Attended by a few dozen of lawmakers, court officers, religious figures, and community leaders, the gathering was essentially an “emergency meeting” of pro-southern ideologues. To say they had much to talk about would be an understatement. Kentucky’s policy of armed neutrality and diplomatic mediation had recently crumbled. Following elections in August 1861—that virtually everyone in the state understood as a referendum on secession—the government in Frankfort veered toward Conservative Unionism and officially backed the Union war effort in September.

The Commonwealth’s governor and chief proponent of neutrality, Beriah Magoffin, wasn’t trusted to head up the recruitment of troops, so a military board was installed to serve as de facto commander(s) in chief. With these developments in mind, and claiming to speak on behalf of “the people of Kentucky,” convention leaders decried the “unfortunate condition of the state.” Moreover, they promised to devise “some means of preserving the independence of the Commonwealth.”

It is worth pausing now, for just a moment, to decode their terminology. By “unfortunate condition,” pro-Confederates at the convention referred specifically to a conspiracy theory in which two-faced politicians in Frankfort had deceived their constituents with false pledges to perpetual, armed neutrality. By way of Machiavellian deception, Unionist double operatives had managed to deliver Kentucky—against the collective will of its populace—directly into the hands of a tyrannical president and his cabinet of fanatical abolitionists. In turn, the aforementioned “independence of the Commonwealth” no longer referred to armed neutrality or a role as negotiator between warring nation-states. The will of the convention was to break away from the Union, one way or another.

For what it’s worth, the conspiracy theory outlined above was half correct when examined in the right light. On one hand, Conservative Unionists had come to a tentative neutrality agreement with Confederate sympathizers believing all the while that they could keep Kentucky in the Union proper. On the other hand, pro-Confederates had also entered into the neutrality pact with ulterior motives—their plan had always been to land Kentucky for the Confederacy. But the people of Kentucky handed the Conservative Unionist position a healthy majority in the 1861 elections and squashed any genuine possibility of a secession ordinance emanating from Frankfort. The idea that Lincoln had forced Kentucky to remain in the Union by brute force in 1861 is largely the stuff of post-war mythmaking; Kentuckians, many of whom supported the institution of slavery, simply believed their chattel safer when backed by Union authority than Confederate.

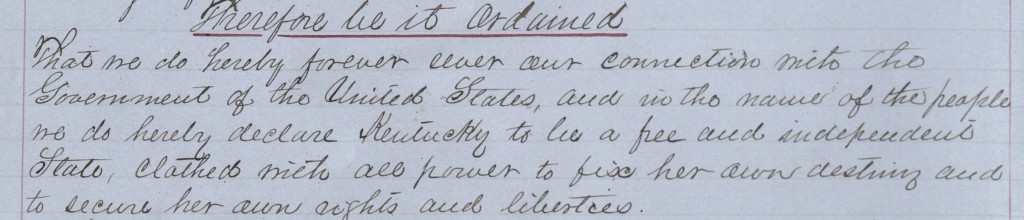

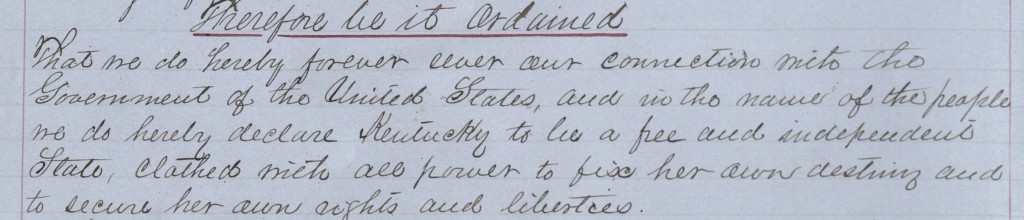

Regardless of these facts, the convention-goers declared Kentucky’s independence.

Therefore be it Ordained That we do hereby forever sever our connection with the Government of the United States, and in the name of the people we do hereby declare Kentucky to be a free and independent State, clothed with all power to fix her own destiny and to secure her own rights and liberties.

And while the initial declaration said nothing of it, it’s safe to presume that everyone in the hall knew precisely which destiny would be fixed: Kentucky would only remain an “independent State” for as long as it took to officially join the Confederacy.

And while the initial declaration said nothing of it, it’s safe to presume that everyone in the hall knew precisely which destiny would be fixed: Kentucky would only remain an “independent State” for as long as it took to officially join the Confederacy.

The newly-formed provisional government set up shop in Bowling Green, Kentucky. It consisted of a Provisional Governor (George W. Johnson), a twelve-man “Council” (that essentially functioned as an unelected general assembly in miniature), and a Secretary of State (who basically served as a gopher, delivering notes for Johnson to the Council and vice versa). Very early on in the business of the provisional government—which met nearly every day from convention’s end in November 1861 until January 1, 1862—Johnson released a message meant to justify the actions of the new government and outline his plan for Kentucky’s future. Below are excerpts from some of the more significant passages:

A profound and happy domestic peace, pervaded the whole country and rewarded their vigilance, until the abolition parties, growing with the growth of the North, determined to interfere with the domestic institutions of fifteen slave-holding States … Their avowed purposes were at war with the words of the Constitution, the decisions of the Supreme Court and the whole usage and history of the government; and when so infamous a party gained possession of the Federal Government, a profound dread of the consequences seized upon the whole nation.

Kentucky desired to mediate and remain neutral between the contending parties. It would have been more wise if she had foreseen the utter ruin which would and always must follow the destruction of Constitutional government, and if she also had drawn the sword with the Southern States for its preservation.

They [ambitious demagogues and fanatics who had seized the Government and outraged the Constitution] had deliberately plotted for years for power to destroy the Constitution with protected Southern institutions; and in the first intoxication of victory, it was species of madness in Kentucky to expect abolitionists to dash the cup untasted from their lips.

The North refused to grant Constitutional amendments for the protection of slave property; and thus the peace conference inaugurated by Virginia and Kentucky, closed its labors an utter failure.

The first and most important duty which is before us is to bring to the Confederate States all our resources for the successful prosecution of this war; and to do all we can to turn the minds of all parties to terms of honorable peace — To the first of these duties you have already turned your attention; and I trust the world will soon see the result of your labors in your organized battalions of brave and dauntless Kentuckians.

According to Johnson, the northern states, led by Lincoln and hordes of abolitionists, had intentionally undermined the Constitution in an effort to trigger bloodshed and the final destruction of southern slavery. Kentucky, for its part, had honorably tried to stop the conflict, but was deceived from outside (by northerners) and from within (by Unionist turncoats). Now, the only option for the preservation of true Republican ideals and individuals freedoms was to join the Confederacy and restore freedom to the Commonwealth by military force—the last resort of “brave and dauntless Kentuckians.”

Ironically, as the ledger book of the provisional government recently added to the CWG-K digital archive reveals, Kentucky’s pro-Confederate state government fell into the same trap that plagued its national counterpart: in order to preserve the individual freedoms and rights allegedly trampled by the federal government, George Johnson and company resorted, out of logistical necessity, to tactics that can at best be described as hypocritical and at worst as bald authoritarianism. This was especially true when it came to procuring money and firearms—essential commodities of any rebellion.

On the former subject, the Council resolved to seek a loan of $25,000 from the Southern Bank of Kentucky at Russellville—one of the few lending institutions not cut off by Union lines. E. M. Bruce of Nicholas County added an amendment to the resolution: “And if said Banks refuse to loan the twenty five Thousand dollars, then said Committee be and they are hereby authorize to co-operate with the authorities of the Confederate States and use such means as will secure the Twenty five thousand dollars desired.” Following a back-and-forth with J. W. Moore of Montgomery County, Bruce suggested another amendment and the resolution eventually read as follows:

Towit: Resolved by the Council of the Provisional Government of the State of Kentucky. That the Governor be and he is hereby authorized and requested to appoint Two or more Commissioners to negotiate a loan from the Southern Bank of Kentucky for the sum of Twenty Five Thousand Dollars for the use of this Government, and if said Bank refuse to loan the Twenty Five thousand Dollars then the Governor is further authorized to use such means as in his judgment may be necessary to obtain said Twenty five Thousand dollars of the said Southern Bank.

In short, the Council granted Governor Johnson the authority to take funds by whatever means necessary—force included, and strongly implied, actually—if the bank refused to loan money on the terms requested by the provisional government. The substitution was adopted and T. L. Burnett and Burch Musselman were dispatched to procure the loan. Later, the appointed commissioners returned with disappointing news. The Southern Bank had refused to loan the provisional government $25,000, largely because even though its directors harbored their own pro-southern sympathies, they fully understood the consequences of funding a rump government’s plot to commit armed treason. In place of the requested $25,000, the bank would only agree to $5,000 to the commissioners themselves, on the condition that the funds be viewed as personal loans—not official Council business. Not seeing any other option, Burnett and Musselman took the deal.

Outraged by the bank’s lack of confidence and the commissioners’ failure to follow directions, the Council refused to accept responsibility for the $5,000 loan and instructed Burnett and Musselman to return the funds. The Council further decreed that Governor Johnson must now step in and “obtain the $25.000 of the said Bank in accordance with the resolution appointing the Commissioners.” This put Johnson in a very uncomfortable spot because on one side, he needed money to fund his government. But on the other, he really didn’t have the ability to make real the authority granted to him on paper by the Council—that is, he had no real means of compelling the Southern Bank to hand over $25,000 in exchange for IOUs.

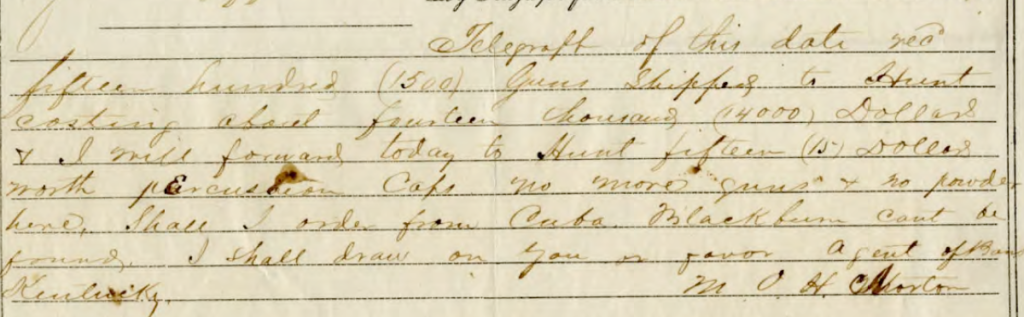

Part of the reason Johnson couldn’t strong-arm the bank is because the provisional government didn’t command an army; a major reason the provisional government didn’t command an army is because they had no recruits; and, they had very few recruits because they had no weapons. This led directly to the previously mentioned effort to procure firearms. Late in December, the Council passed a bill that called for all free, white, able-bodied men between the ages of 18 and 45 who would not volunteer for active service in the Confederate military to produce any and all guns in their possession for inspection by an appointed official. Each county would have an inspector, the inspector would decide which guns were worthy of confiscation, and provide the then disarmed citizen of Confederate Kentucky a receipt to be repaid after the successful waging of the war.

Another stipulation of the inspection program was that anyone who failed to deliver a gun for inspection or who tried to “secrete his arms” would be arrested. The local constable or sheriff would take the offender into custody, but the bill also granted the gun inspector himself with the power to detain citizens. Anyone caught violating these rules would be fined $50 or jailed and, more startling, would be “disarmed as an enemy and his arms delivered to the Inspector.” Any able-bodied men who legitimately did not own a gun, but was worth at least $500 in taxable property had the option to take an oath before the inspector (attesting to his lack of firearm) but then had to pay the inspector $20, for which the citizen would receive a receipt. This $20 payment would be considered a debt against the Confederate government to be repaid at the (successful) conclusion of the war. In other words, more involuntary payments made under the guise of patriotic loans.

Johnson and his Council frequently lambasted Lincoln as a tyrant; they accused the federal government of holding the Union together at the expense—and against the will—of its actual inhabitants. Secessionists pointed to the results of the presidential election of 1860 as evidence: Lincoln had not won a single southern state, or even a single border western state. Nor had he managed to capture more than 40% of the popular vote. So how would he now claim to have a mandate from the people to preserve the Union at any cost?

In reality, this was probably the biggest case of the pot calling the kettle black in the history of Kentucky. Johnson was not elected by anything resembling a plurality of the people and neither were the councilmen who then presumed to govern them. The ascendance to power of Kentucky’s provisional Confederate government—in as much as the group ever actually ruled over anything—came in direct opposition to the collective will of the Commonwealth. The state-wide elections of 1861 make that perfectly and unavoidably clear.

More illuminating, though, is how the plans hatched by the provisional government to grab guns and break banks reflected the broader problems—and fundamental intentions—of the national Confederate government in microcosm. For years historians have pointed out that to run the rebellion effectively from Richmond, Jefferson Davis had to take near-dictatorial control of its management; or, put another way, that he had to sacrifice the supposed core cause for which the Confederacy fought for sake of actually winning the fight. The situation in Kentucky was the same in principle—because just like the case of Davis and the national Confederate government, it ultimately exposes yet again the extent to which states’ rights was never really the main catalyst or prize of the conflict.

Matthew C. Hulbert is an Assistant Editor of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.

SOURCES: Provisional Government of the State of Kentucky, Journal (specifically documents KYR-0004-033-0027, KYR-0004-033-0036, KYR-0004-033-0001, KYR-0004-033-0029).

And while the initial declaration said nothing of it, it’s safe to presume that everyone in the hall knew precisely which destiny would be fixed: Kentucky would only remain an “independent State” for as long as it took to officially join the Confederacy.

And while the initial declaration said nothing of it, it’s safe to presume that everyone in the hall knew precisely which destiny would be fixed: Kentucky would only remain an “independent State” for as long as it took to officially join the Confederacy.