A few weeks ago, CWG-K was approached by Feliks Banel, a Seattle historian and radio broadcaster, seeking information about the man who named Washington state. A Kentucky Congressman in 1853, it seems, had suggested that Columbia—the name under which the territorial bill had been submitted—might be confused with the District of Columbia. So, Richard H. Stanton suggested the compromise name of Washington—which, he apparently thought, wouldn’t get confused with any other important center of political power in that District.

So, Feliks asked, did anyone in Kentucky remember this Richard Stanton? Turns out, the answer is generally no. Not in Maysville, where Stanton lived and is buried. Not in Powell County, where the county seat is named after him. But he was well known to CWG-K.

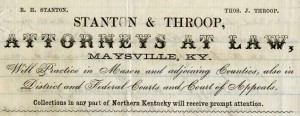

What do CWG-K documents tell us about Richard Stanton? He and his law partner (and brother-in-law) Thomas Throop were two of the most important attorneys in the state when the Civil War came to Kentucky. Stanton had undertaken the gargantuan task of compiling a revised and annotated edition of the Kentucky Revised Statutes in 1860, making Stanton a household name to whom attorneys and judges across the state turned for the latest interpretation of state laws. On a regional level, Stanton was Commonwealth’s Attorney (akin to a district attorney in most other states) for the Tenth Judicial District serving Mason, Lewis, Greenup, Rowan, Fleming, and Nicholas Counties.

But in CWG-K documents, Stanton conducts very little business as a Commonwealth’s Attorney. He appears most frequently in private practice requesting pardons for their clients, and they seem particularly close to the Democratic administration of Beriah Magoffin.

Why was such an influential attorney like Stanton unable to hold his position as Commonwealth Attorney after 1861? The first clue came from a letter of his partner Tom Throop to Magoffin in November 1860:

Your positions are undoubtedly correct, and if our union as states is preserved the movement must come from the north. They must abolish all these nullifying laws, carry out the provisions of the constitution, as to the comity between the states, carry out the provisions of the fugitive slave act, respect their so called personal liberty bills, allow the free transit of persons from the south with their families & property through their territories; acknowledge by their acts, not words only, that we as states have an equality of rights, with them: unless this is done, our union is a farce, it is effete, a humbug & a cheat.

Throop certainly seems a John C. Breckinridge Southern Democrat, but did he speak for his friend Stanton? Union General “Bull” Nelson certainly seemed to think so. He arrested Stanton and six other Maysville men on October 2, 1861. According to Nelson (a native Maysville man, himself) the group were “traitorous scoundrels who were engaged in fitting out men for the Southern army, subscribing moneys, getting up nightly drills and doing the manner of things usual among the secessionists. …with the Hon. R. H. Stanton at their head.”

In another letter, Nelson asserted that “This man Stanton is the head of secession in Northeast Kentucky” and that “He has harbored in his house an officer of the Confederate Army” and forwarded 259 men from the area to Humphrey Marshall’s rebel forces in Prestonsburg, Kentucky. This was entirely plausible. Stanton’s son returned from a law practice in Memphis at the outbreak of the war to raise a company of troops in Mason County for Confederate service. Henry T. Stanton may have been the very officer harbored by his father.

Whether with evidence or speculation, Nelson concluded that Stanton “is the soul of rebellion in this part of Kentucky.” “[M]orally a very Catiline” whose arrest “has struck secession dumb here.”

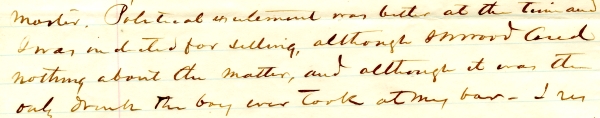

First taken to Cincinnati, then to Camp Chase in Columbus, Ohio, and finally to Fort Lafayette in New York City, Stanton proclaimed his innocence the entire time. As did many Kentucky secessionists facing the state and federal government crackdown on wartime dissent, Stanton proclaimed himself a strict neutralist. In a letter to Secretary of State Seward, Stanton argued that “we were in favor of Kentucky maintaining a neutral position in the contest…and advocated that policy, hoping that the State would be in a position to maintain peace within her borders and mediate between the two sections.”

Eventually, the Lincoln administration felt enough political pressure from undoubtedly loyal Kentuckians (including a petition from a majority of state legislators) and released Stanton on December 17, 1861, after taking the loyalty oath (read the whole case file in the OR, Series II, Volume II, pp. 913-33). Stanton & Throop continued to practice—carefully avoiding such overt political statements as Throop had made to Magoffin just after Lincoln’s election—for the rest of the war.

From the politics of Manifest Destiny to the mechanics of Confederate recruiting in Union territory to the ever-important American debate over civil liberties and dissent during wartime, Richard Stanton should not be a name that Kentucky historians forget again. Even at this stage, CWG-K has identified a host of mid-level political players like Richard Stanton, and as the project moves forward into annotation and social networking—identifying each unique individual mentioned in our documents and linking them and their known associates together into a massive research platform—we will find many more. What new life story will CWG-K uncover next?

Patrick A. Lewis is Project Director of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.