[This is the second installment of a four-part series, read part one here.]

In the summer of 1862, orders from General J. T. Boyle meant to identify Confederate sympathizers and persons who had demonstrated disloyalty to the Union set off a wave of political detentions of Kentucky citizens. The authority over these political arrests and investigations, which originally rested with the State Department, had been transferred to the War Department in February 1862.[1] Once incarcerated in Camp Chase, prisoners discovered they often had little recourse and few means to expedite their cases. As James Russell Hallam complained in his letter to Governor James Robinson, “I have sought in vain for some tribunal either civil or military before which I could have my case investigated.” Testimony of friends and neighbors, the lawyer seemed certain, would allow him to refute the “the false & scandalous charge” against him, which, he insisted, was “unsustained by any shadow of evidence.”[2] Hallam had sent a petition to the War Department that swore his loyalty to the United States government, along with supporting affidavits, all the while “praying a speedy investigation.”[3] Assuming the delayed reply meant his case had been overlooked, Hallam asked Robinson to intercede.

He appealed to the governor’s knowledge of him over their long acquaintance. “You have known me personally for twenty years,” Hallam wrote, “& I feel confidant I am in your opinion, entitled to some sort of credence when I positively & solemnly assert that I have been guilty of no act or word disloyal to the Government under which I was born.” “On the contrary,” Hallam insisted, “since the rebellion began I have to the best of my ability & opportunities sustained the cause of the Union & abhored & repudiated secession & the rebellion.” Lest he leave any doubt, Hallam declared, “My earnest wishes & hopes are for the speedy crushing of the rebellion & the restoration of the Union as it was.”[4] After he wrote his initial appeal, Hallam realized that though they were long-acquainted, Robinson had no first-hand knowledge of his position on secession. He wrote a follow-up letter the next day, August 19, in which he named the Kentucky Adjutant General and two state senators as character references to support his claims of Union loyalty.[5]

Hallam’s eagerness to clear his name and to enlist anyone and everyone he thought could help him do it are not surprising, given that his arrest on July 18, 1862, was his second detention on suspicion of disloyalty. He was arrested on October 5, 1861, and held in federal custody until December 4 of that year. He took the oath of allegiance upon his release and claimed to have “lived faithfully up to it, both from duty and inclination” ever since.[6] Amid the July military emergency, Hallam volunteered to defend Newport. While helping “in good faith” to organize the defense of his hometown, he was arrested by Henry Gassaway and sent to Camp Chase.[7] All of this he wrote to Edwin Stanton on July 25, along with assurances of his support for the Union. “I deny the constitutional right of secession [and] look upon & denounce secession as a crime,” declared Hallam, who added that he had “sympathized with the United States government in the present rebellion.”[8]

Hallam also explained to Stanton why he though his loyalty had come under scrutiny. Over his objections, three of Hallam’s sons had enlisted in the Confederate army. “I declare that my sons joined the rebel cause against my strong remonstrances desire & command,” Hallam wrote.[9] Since their enlistment, two had been captured and imprisoned—one at Alton, Illinois, and the other at Camp Morton, Indiana. While advocating for his own release, Hallam had also been trying to talk some sense into his wayward children. “Since their capture,” he wrote to Stanton, “I have been untiring in my efforts to reclaim them to their allegiance to the U.S. & I think I have succeeded. My letters to them & their answers to me will sustain me.”[10]

Despite his best efforts, Hallam’s release would not happen quickly. The War Department was only just appointing a special commissioner to investigate the cases of the Camp Chase political prisoners. Reuben Hitchcock was notified of his appointment on August 13.[11] His instructions from the War Department, dated August 23, were to interview each prisoner and examine evidence related to the person’s guilt or innocence and their “intentions toward the Government whether loyal or hostile.” He was directed to make a report that included his recommendation “as to whether the peace and safety of the Government requires [the prisoner’s] detention or whether he may be discharged without danger to the public peace.” The War Department advised Hitchcock that he was granted “the largest discretion” in his investigative powers and except in rare circumstances, his recommendations would be followed. Hitchcock was also advised that the War Department wished to “forbear the exercise of power,” as much as possible without sacrificing the security of the government.[12]

Although in June he had opposed the release of Camp Chase political prisoners on grounds that it hampered the efforts of the Union army in Kentucky, by early August, General J. T. Boyle complained that “Prisoners [were] sent to prison for the most trivial causes by provost-marshals” who had ostensibly been acting on his orders.[13] Boyle found that he was unable to secure the release of even Union men whose loyalty could be vouched for by the U.S. attorney.[14] Such arrests for “trivial causes” strained an already tenuous political situation in Kentucky. On August 12, J. B. Temple, President of the Military Board of Kentucky, warned Abraham Lincoln that “indiscriminate arrests” played poorly on public sentiment. Specifically, Temple objected that “Quiet, law abiding men holding State-rights dogmas are required to take a [loyalty] oath repulsive to them or go to prison.”[15] The next day, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton communicated to Boyle that the power to arrest Kentucky civilians should be “exercised with much caution and only where good cause exists or strong evidence of hostility to Government.”[16]

In response, Boyle again attributed the problem to the actions of provost marshals, some of whom he had appointed and others of whom were already in office when he took command. According to Boyle, “many arrests are made by provost-marshals without my authority and in some cases without proper cause.” He explained that in some cases, the provost marshals had sent the prisoners to Camp Chase, where he had no control over the prisoners. He reminded Stanton that he had already asked the War Department for authority over the Camp Chase prisoners, presumably so he could secure the release of loyal Unionists wrongfully incarcerated but also those who had been “sent to prison for special purposes of public interest” who remained in prison after the perceived threat had passed. Boyle complained that “For some reason this control of the prisoners is withheld from me.” But he also insisted that some of the arrests were justified. “There are many so-called Union men in Kentucky who still cling to the hope of reconciliation and believe in a policy of leniency,” he explained, although the general strongly opposed such a policy. “I believe in subjugation,” Boyle declared, “complete subjugation by hard and vigorous dealing with traitors and treason.” “Any other policy,” he predicted “will be ruinous to us in Kentucky.” Although he expressed willingness to adopt any policy the President or Secretary of War directed regarding arrests, he added that it was only “lukewarm Union men” who complained.[17]

A little more than a month later, on September 15, James Robinson and Joshua Speed directed messages to President Lincoln urging that the authority for arrests be placed with the Kentucky governor. The “irregular and changing system of military arrests,” claimed Robinson, “does more harm than good.”[18] Speed, a longtime friend of Abraham Lincoln, reported that “Annoying arrests continue very much to our detriment.” He advised the President, “The good of the cause requires that you should direct Boyle to leave this whole matter to our loyal Governor.”[19] Later that day, Edwin Stanton ordered Boyle to “abstain from making any more arrests except upon the order of the Governor of Kentucky.”[20] In reply, Boyle insisted that he had been sparing in his use of the power of civilian arrest and that reports to the contrary were false. He repeated his claim that the complaints were made by men of questionable loyalty. And he declared that “There is a bounty of absolute security and protection to be a rebel in Kentucky.”[21] Boyle warned that if the government did not “put down the rebels in our midst…the war will have to be fought over in Kentucky every year.”[22] As it was, the general reported that in Louisville, Confederate flags were thrown from windows “with impunity,” and he defiantly informed the Secretary of War that he had countermanded the order regarding arrests.[23]

Although Boyle seems to have borne the blame for those operating under his command, other accounts support his contention that some provost marshals were, as Stanton later described, “rigorously and excessively arbitrary and harassing to the people of Kentucky.”[24] Instances were reported of provost marshals making arrests and accepting bribes to release the prisoners, actions Stanton condemned as “inexcusable outrages.”[25] Indeed, in October, he directed that provost marshals found to have abused their authority in such a manner should, themselves, be arrested.[26] On December 18, 1862, Lt. Colonel William B. Sipes, the military commander at Covington and Newport who assumed the post in September, acknowledged that the power to arrest and imprison civilians had been “too indiscriminately exercised,” but he also noted that regular military officers were rarely the problem; more often, the arrests had been made by civilian provost marshals. “The will of these gentlemen was the law,” Sipes wrote, “and in many instances they appear to have exercised their official functions with but little regard for any rule of action either civil or military. Many of them kept no records, and instances are not rare where prisoners were confined by their order for months without the shadow of a written charge of any kind against them.”[27] He also described instances in which provost marshals had confiscated property. “Cases are known,” Sipes, reported, “where the effects of individuals were seized and appropriated without any military or legal sanction and in violation of all principles of justice and right.”[28] Sipes blamed such practices for “much of the bad feeling” in Kentucky and recommended that instead of civilian appointees, the provost marshal positions be filled by regular army officers.[29]

One provost marshal, Henry Gassaway, would become the target of multiple civil lawsuits by people he had arrested for disloyal conduct. In April 1865, Gassaway was the defendant of at least twenty-one lawsuits filed in Campbell County Circuit Court, each one seeking damages for false imprisonment in the amount of $50,000. Gassaway turned to the War Department for help and, in explaining his situation, provided a detailed account of his actions as provost marshal and the military emergency that led to several arrests. Gassaway’s account casts him, not as a rogue provost marshal, but a public servant who dutifully followed the orders of General Boyle. Gassaway wrote that the plaintiffs filed their lawsuits around the same time “as if acting in concert” and that the cases had continued as though “Originating in a desire to obstruct military operations and having the Effect of Embarrassing and oppressing the constituted authorities of the Government of the United States.”[30] Gassaway had the right to have the lawsuits removed to federal court, but Judge Advocate A. A. Hosmer had another idea. In a similar case, the Bureau of Military Justice had concluded that it was “competent,” under the proclamation of marital law, for the general commanding the military district of Kentucky to “restrain, by such means as in his discretion might be deemed needful” the continuation of nuisance lawsuits filed against U.S. officers for actions taken in the course of their duties. Hosmer advised that General Palmer, then in command of Union forces in Kentucky, could “take a needful action,” implying that he could simply re-arrest the troublemakers.[31]

The problem William Sipes described, of civilians being imprisoned for months without so much as a written charge against them, was contrary to Boyle’s original order, but that appears to be what happened to James R. Hallam. Although his appeal to Governor Robinson suggests Hallam had not yet received it, the Commissary General of Prisoners, William Hoffman, penned a letter to Hallam dated August 10. Hoffman acknowledged receipt of a letter Hallam had sent him directly; one that Hallam had sent to Ohio governor David Tod, which had been forwarded to Hoffman; and the petition that Hallam had sent via the Camp Chase post commander, presumably the one Hallam mentioned in his letter to James Robinson. Colonel Hoffman assured Hallam that his case had been referred to the Secretary of War “in a way if possible to secure speedy action upon it.” He also advised Hallam that he would probably be required to obtain affidavits from friends in Kentucky to establish his loyalty.[32] To move the process along, Colonel Hoffman had inquired into the charges against Hallam and two other political prisoners.[33] The answer he received was that there were no charges against Hallam. The colonel concluded that “there would therefore seem to be no reason for his further detention.”[34] That was on August 14, 1862, before Hallam wrote to the Kentucky governor. But Hallam was detained for two more months. He was required to take an oath of allegiance and finally released on October 14, 1862.[35] The following year Hallam filed a lawsuit in Kenton County against Henry Gassaway and several other men for wrongful imprisonment. His civil suit continued at least through April 1864, but no record of the final judgment has been located.[36] Whether or not Hallam’s was the earlier case referred to by the judge advocate, given A. A. Hosmer’s advice on how to deal with the coordinated lawsuits in Campbell County, it is doubtful that Hallam’s lawsuit met with any more success.

[1] Neff, Justice in Blue and Gray, 157.

[2] James R. Hallam to James F. Robinson, 18 August 1862, Office of the Governor, James F. Robinson: Governor’s Official Correspondence File, Military Correspondence, 1862-1863, R2-3 to R2-4, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY. Accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, http://discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0001-027-0005.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] James R. Hallam to James F. Robinson, 19 August 1862, Office of the Governor, James F. Robinson: Appointments by the Governor, Military Appointments, 1862-1863, R2-116 to R2-117, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY. Accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, http://discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0001-028-0003.[6]

James R. Hallam to Edwin Stanton, 25 July 1862, Case Files of Investigations by Levi C. Turner and Lafayette C. Baker, 1861-1865, NARA RG 94, Microfilm Series M797, Roll 0007, Case File 193, p. 6, accessed via Fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/257035312

[7] Ibid., 5

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., 5-6.

[11] Edwin M. Stanton to Reuben Hitchcock, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of theUnion and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1880-1901), series 2, vol. 4: 380 (hereafter OR).

[12] L. C. Turner, “Instructions for Hon. Reuben Hitchcock, special commissioner to investigate and to report on the cases of state prisoners held in custody at Camp Chase,” OR, series 2, vol. 4: 425.

[13] Jeremiah T. Boyle to Edwin M. Stanton, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 17; Jeremiah T. Boyle to Edwin M. Stanton, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 412 (quote 412).

[14] J. T. Boyle to Edwin M. Stanton, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 412.

[15] J. B. Temple to Abraham Lincoln, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 378.

[16] Edwin M. Stanton to Jeremiah T. Boyle, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 380.

[17] Jeremiah T. Boyle to Edwin M. Stanton, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 412-13.

[18] James F. Robinson to Abraham Lincoln, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 517.

[19] James F. Speed, to Abraham Lincoln, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 517.

[20] Edwin M. Stanton to Jeremiah T. Boyle, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 517.

[21] Jeremiah T. Boyle to Edwin M. Stanton, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 517.

[22] Ibid., 517-18.

[23] Ibid., 518.

[24] Edwin M. Stanton to Horatio G. Wright, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 616.

[25] Edwin M. Stanton to Horatio G. Wright, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 616.

[26] Joshua F. Speed to James F. Robinson, 14 October 1862, Office of the Governor, James F. Robinson: Governor’s Official Correspondence File, Military Correspondence, 1862-1863, R2-95 to R2-96, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort, KY. Accessed via the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition, http://discovery.civilwargovernors.org/document/KYR-0001-027-0045.

[27] William B. Sipes to Horatio Wright, OR, series 2, vol. 5: 96.

[28] Ibid., 96-97.

[29] Ibid., 97.

[30] Letters Received by the Office of the Adjutant General, Main Series, 1861-1870, NARA RG 94, Microfilm Series M619, Roll 0370, File No. K250, p. 6, accessed via Fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/301027835.

[31] Ibid., 8.

[32] William Hoffman to James R. Hallam, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 371-72.

[33] William Hoffman to Col. S. Burbank, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 365.

[34] William Hoffman to C. P. Buckingham, OR, series 2, vol. 4: 391.

[35] “Roll of Prisoners of War at Camp Chase Ohio,” Selected Records of the War Department Relating to Confederate Prisoners of War, NARA RG 109, Microfilm Series M598, War Department Collection of Confederate Records, Roll 24, p. 190-91, accessed via Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/interactive/1124/M598_24-0241.

[36] Kenton County Circuit Court, Covington, Order Books, 1845-1977, Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, March 9, 1863-April 16, 1864, 291, 344, 357, 557.

Christina K. Adkins has a PhD in American Studies and works as a volunteer on the CWGK Team. Her work focuses on slavery and cultural memory.

Check back with CWGK every Monday in January to read a new editions to Political Detentions in the Civil War.

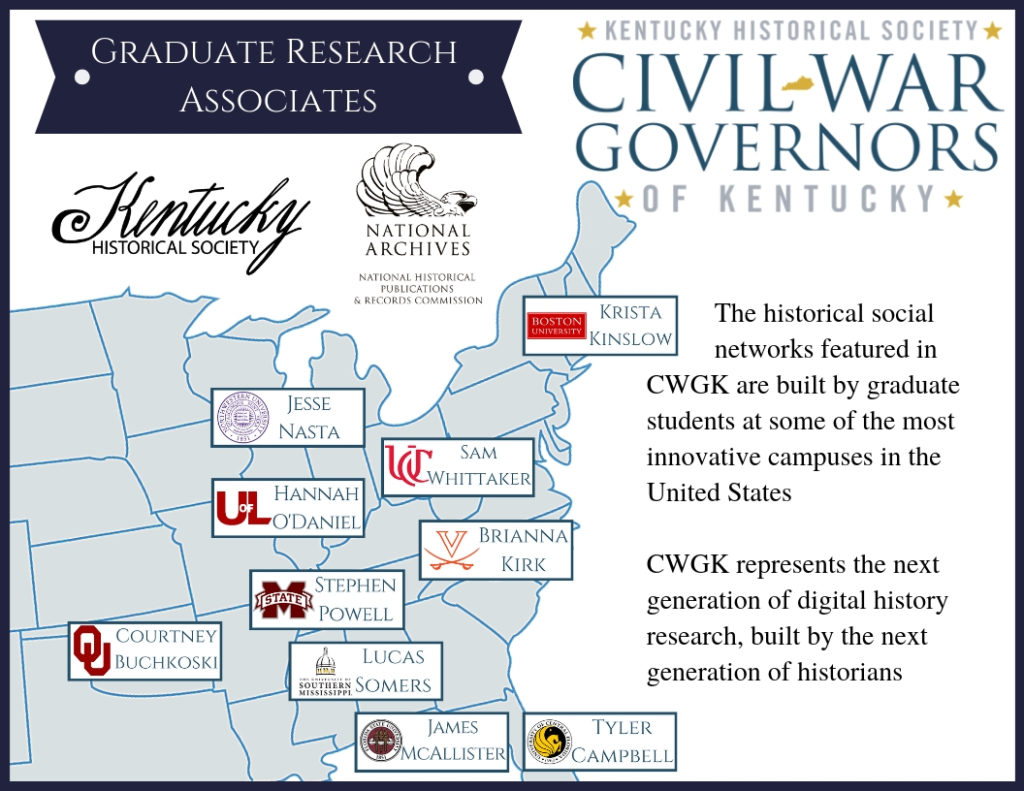

For the fourth time, the Civil War Governors of Kentucky (CWGK) was awarded a grant from the

For the fourth time, the Civil War Governors of Kentucky (CWGK) was awarded a grant from the