2015 was an eventful year for the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition. Numerous fellows utilized the power of the ever-growing database (you can apply to be one here), we are steadily approaching the launch of an Early Access edition of 10,000 documents and transcriptions and a Beta prototype. Governor’s Day — an interactive open house introducing the project to other departments at the Kentucky Historical Society — was a major success.

To recap the year, we’ve organized a series of “Best of” lists that chronicle everything from our individual takes on the most powerful people of Civil War Kentucky to the most memorable deaths to time travel (more on this anon). We hope you’ll enjoy reading these lists these as much as we enjoyed creating them.

POWER RANKINGS: Based on their own criteria, each member of the CWG-K editorial staff was asked to rank a “Power 5” group of figures found in the database.

Tony

- George W. Johnston – Powerful Judge of the Louisville City Court, a Louisville/Jefferson County pardon application was never complete and rarely received a positive reply without his signature.

- John B. Huston – Besides competing for the worst handwriting award for Civil War Kentucky—stiff competition from James F. Robinson and James Guthrie—Huston was a power broker, attorney and state legislator from central Kentucky, whose endorsement of a pardon application carried a lot of weight with multiple Kentucky governors.

- John B. Temple – Attorney, banker, and president of the Kentucky Military Board—Temple exerted a lot of power in all Kentucky military matters. He and the Military Board of Kentucky were de facto Commander-in-chief of Kentucky, slowly whittling away Beriah Magoffin’s military authority with the aid of the Kentucky General Assembly.

- George W. Norton – President of the Southern Bank of Kentucky, he was a Magoffin ally, made sizable loans the Commonwealth of Kentucky to support Magoffin in his efforts to purchase arms early in the war. Other banks made similar investments, yet Norton appeared to have the ear of the governor.

- C. D. Pennebaker – Lawyer, politician, Colonel of the 27th Kentucky Infantry, and Kentucky Military Agent in Washington, DC. He served in the legislature, commanded troops in battle, and served in a civilian military post for Kentucky in DC. In addition to this he wrote the more thorough letters and reports. Kudos Mr. Pennebaker!

Matt

- W. T. Samuels – Not unlike Matt Damon’s character in The Good Shepherd, Samuels had the dirt on everyone following his stint as state auditory. Given his knowledge of everyone’s finances and his legal prowess, he was a potential kingmaker in the Blue Grass. (In other words, there’s a reason he’s one of the few through-and-through Unionists to remain powerful in state government post-1865.)

- D. W. Lindsay – He commanded a crew of paid guerrilla hunters under the heading of “secret police”; these men, like Edwin “Bad Ed’ Terrell, were paid to track down and kill Kentucky’s most notorious bushwhackers.

- Stephen Burbridge – Though he technically fell under the authority of Thomas Bramlette in Kentucky, Burbridge more or less did as he pleased, which included deeming other powerful Union officers (like Gen. John B. Huston) disloyal and having them arrested on behalf of President Lincoln.

- Thomas Bramlette – As governor he oversaw nearly all of the state’s wartime activities—and was still expected to keep civil government afloat.

- E. H. Taylor, Sr. – Taylor was a member of the influential Military Board (which oversaw military purchases for the state) at the same time he helped run one of the state’s major money-lenders. If you needed a loan—and Kentucky always needed a loan—this was the man to see.

Whitney

- Thomas Bramlette – He takes first place by virtue of holding the highest office for the longest amount of time, evidenced by almost 3,000 documents.

- John W. Finnell – As Adjutant General, principal military advisor to Gov. Bramlette while a war was raging, he was in a very influential role.

- Samuel Suddarth – Serving as Quarter Master General, Suddarth was tasked with keeping the troops supplied by managing the ordering & distributing of supplies essential to the war effort.

- James F. Robinson – Though he served as Governor for a short time, he was part of a compromise wherein the Confederate-leaning Magoffin agreed to step down and let Robinson, a moderate, take over. Interestingly, since he never resigned his Senate seat, he technically filled both rolls simultaneously.

- James Garrard – He served as State Treasurer throughout the war, and as Mayer Amschel Rothschild allegedly said, “Let me issue and control a nation’s money and I care not who makes the laws.”

Patrick

- James F. Robinson – Don’t let his one-year term as Governor fool you, Robinson played state politics as adeptly as Frank Underwood could have done. While we can’t know if he pushed anyone in front of a train, Robinson adeptly turned down the senate speakership before having a cabal of Lexington friends arrange Magoffin’s resignation and his convoluted ascension to the Executive Mansion. As George Washington showed, the best way to accrue power is to look like you don’t want it. More astonishingly, Robinson refused to vacate his senate seat, leaving him free to return to harassing the Lincoln administration via the Committee on Federal Relations after Bramlette took office.

- Hamilton Pope – Louisville politics ran through Hamilton Pope. An old-Whig and former Know-Nothing, Pope was undoubtedly part of the closed-door decision that cut Louisville German and Irish immigrants out of independent regiments and elevated his brother, Curran Pope, to a Colonelcy. In addition to being an invaluable petition signature for anyone hoping for a pardon out of the Jefferson Circuit Court, Pope also runs point on using city government and the police department to enforce (increasingly irrelevant) fugitive slave laws.

- Rufus K. Williams – A fiercely Unionist circuit judge from the overwhelmingly Confederate Jackson Purchase, Williams raised a military unit and used his recruits to broker a deal for himself. When the time came to muster his troops into federal service, Williams traded a permanent military commission for a seat on the Kentucky Court of Appeals (the forerunner of the state supreme court) vacated by rebel sympathizer Alvin Duvall—ditching a hostile local electorate for a secure post backed by the statewide Unionist majority.

- Madison C. Johnson – His brother, rebel governor George W. Johnson, gets all the headlines in the family, but Madison Johnson controlled most of the available credit in the Bluegrass via the Northern Bank of Kentucky in Lexington. Johnson arranged hundreds of thousands of dollars in military loans to the Commonwealth in 1861-62—and was never hesitant to hold up the next installment to ease along a friend’s military commission. His loans to the state, backed by eventual federal repayment, helped his bank weather the collapse of many borrowers’ fortunes after slavery ended in 1865.

- Sherley & Woolfolk – This Louisville corporate duo of Zachariah M. Sherley and Richard H. Woolfolk often appear together in documents. Their firm ran a number of steamboats along the Ohio River and operated an outfitting business that sold supplies to others. Consequently, whether the state needed to move a battalion from Maysville to Paducah or buy a few barrels of ships biscuit to feed a hungry regiment, Sherley & Woolfolk were ready and willing to profit. That they signed insider political petitions under their corporate name shows an awareness of the importance of their business to the management of the war and, perhaps, some intuition for hammering home a branding message.

MOST MEMORABLE NAMES: Our editors have compiled a list of the most memorable names encountered in the CWG-K database in 2015.

- Greenberry Tingle

- Swift Raper

- Wam Timbar (involved in a hatchet-throwing case, if you can believe it)

- Green Forrest

- August Worms

MOST MEMORABLE DEMISE: If you’ve followed the CWG-K blog over the past few months, it’s readily apparent that the database has no paucity of unusual and/or gruesome deaths. Each editor has selected the most memorable demise.

Tony

- Jane Doe Murder Victim – In October 1865, evidence was presented concerning the corpse of a woman, approximately twenty-five years old, found on the outskirts of Louisville. The following is a description of her condition: “Her wounds are as follows a cut over each Eye one on forehand Forehead one just in front of Right Ear. Several Bruises on inside of right thigh and a wound which looked as though the flesh was twisted out her intestines was puled from her body through the Fundament Showing an act of the moste Diabolical rufianian the intestines cut or pulled loose from her body. Her cloths were all torn off of her not a Partickel remaining on her except one garter. Her right arm had been amputated just below the shoulder. the Evidences was plain of a sever strugle with some one from all I can learn I think a Negro did it.”

Matt

- Ewing Litterell – An uninvited Litterell drunkenly barged into the home of James Savage, proclaimed himself “a stud horse” and boasted that he’d had sexual relations with all of the women in the house (and that he would do it again whenever he pleased). Savage let a full load of buckshot — which he fired into Litterell’s chest — serve as a “no you won’t.”

Whitney

- Philip Medard – In January 1864, Philip Medard of Jefferson County died of cold and starvation after his son, Jacob Medard, “did confine & Starve his said father in an out house & kitchen & did starve and freeze him the said Philip by refusing to provide meat & food & clothing for him, & by thus exposing him to the weather.” There are definitely more violent deaths in the CWG-K database, but to date, only one happened in the out house.

Patrick

- Colonel Francis M. Alexander – In what seems to have been an un-diagnosed case of post-traumatic stress disorder, Alexander drew a pistol on and killed a good friend without any motive or memory of the incident. His pardon petition is a moving account of a man coming to grips with his actions and his state of mind. “The exciting circumstances of the rebellion and its fearful consequences…which in rapid and mournful succession swept over his native, and beloved State, have Come upon his anxious and troubled mind with such force, that many events have transpired in his history during the last four years of his country’s trial, which appear to him almost as a dream.”

MOST OUTRAGEOUS PARDON: A major component of the CWG-K archive is requests for executive clemency. Each member of the editorial staff was tasked with identifying the most memorable pardon of 2015.

Tony

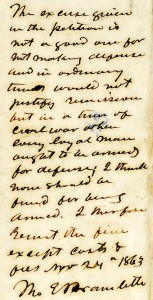

- Otha Reynolds – In May 1862, Peter Gastell jumped bail and caused his bondholder, Reynolds, to forfeit $1000 to the court. That is, until Reynolds petitioned Governor Thomas Bramlette for clemency. Bramlette gave no legal justification for issuing Reynolds a remission, but said this: “Being in a merciful mood Ordered that this forfeiture except costs & fees be remitted.”

Matt

- Michael Foley – An Irish rail worker and former Union vet, Foley believed that Merritt and Vardiman Dicken were pro-Confederate guerrillas on the run. In reality, the Dicken brothers were themselves fleeing from an attack by pro-Confederate bushwhackers. Foley attempted to detain the brothers and killed Merritt in the process. Governor Thomas E. Bramlette granted Foley a full pardon on the logic that it was better to accidentally kill men who might not have been guerrillas than to let any potential guerrillas escape unharmed.

Whitney

- Garrett Whitson – Supporters of Garrett Whitson successfully requested his pardon for murdering violent melon thief, John Spikard. In the petition, they do not claim his innocence, but rather report that Whitson was convicted on the flimsy evidence of two notorious prostitutes, relatives of the deceased. That, combined with his ill health and large family, was enough to procure his release.

Patrick

- Lawrence County Lynch Mob – In KYR-0001-004-3193, the members of a lynch mob on the Kentucky-West Virginia border preemptively write to Governor Bramlette late in 1865 after they have caught and summarily executed members of a pro-Confederate guerrilla band which had murdered many men in their community. “In getting Rid of them People Did not think that the act was unlawful & might get those Engaged in it in Trouble They only felt that Each man woman and child in our Valley was safer than before.”

TIME TRAVEL MEETING: Finally, we’ve asked each editor to select one character from the CWG-K archive that they would most like to spend an hour with when the Flux Capacitor becomes a reality.

Tony

- Richard Hawes – Mostly to ask, where were you? What did you do for three years after you were installed as Provisional Governor of Kentucky?

Matt

- Joseph Swigert – In a word: bourbon. The Swigert family owned the Leestown Distillery (which would later become E. H. Taylor’s O. F. C. Plant, then the George T. Stagg Distillery, and today Buffalo Trace).

Whitney

- Sarah Bingham – It’s safe to say that upon moving to Grant County in 1866, Ms. Bingham did not receive a warm welcome from the neighbors. The women of the area “were of the opinion that the morals of the neighborhood would not be improved by having in their midst a common prostitute.” When her cabin burned down, nine local men indicted for arson. The petitioners claim these men were honorable, respectable citizens who would never commit such a common crime and accuse Sarah Bingham of burning her own house down with the intent to disgrace these men. Their petition was refused by Bramlette, who, like myself, must have realized there was more to this story.

Patrick

- Benjamin F. Buckner – Because I feel like I’ve already spent so much time with him.