Be sure to read the Transcription of this document as well as Part One and Part Two of the analysis.

Atchison, Samuel Ayers. (1810 – 1869) Kentucky native and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney and real estate agent. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 22; Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, Louisville, Sixth Ward, p. 13.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0023, KYR-0001-004-0024, KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-2939, KYR-0001-004-2944, KYR-0001-004-3407, KYR-0001-033-0011.

Bacon, Byron. (1835 – 1900) New York native and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Practiced in partnership with Martin Bijur after 1864. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 24; Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, Louisville, Sixth Ward, p. 32.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0454, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-2270, KYR-0001-004-3407, KYR-0001-020-0828, KYR-0001-031-0160.

Baker, Charles Samuel. (? – ?) Louisville, Kentucky, saddler. J. D. Campbell’s Louisville Business Directory, For 1864 (Louisville: L. A. Civill, nd.), 103.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Barbour, Catherine. (c. 1805 – ?) Native of France and Louisville, Kentucky, resident. Resided in 1860 with her husband, Constance Barbour, and son, Joseph. Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, District 1, p. 36.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Barbon, John G. (c. 1830 – ?) Native of Spain and Louisville, Kentucky, resident. A laborer by trade. Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, District 1, p. 63.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Beattie, James A. (1832 – 1893) Missouri native and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Practiced in partnership with William S. Bodley and Alexander Casseday. Judge Advocate of the Kentucky State Guard. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 30, 344; Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, Louisville, Fifth Ward, p. 62; Kentucky, Death Records, 1852-1953 [database on-line via Ancestry.com], Jefferson County, 1893, p. 113.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0439, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-007-0476, KYR-0001-017-0314, KYR-0001-017-0337.

Bender, F. (? – ?) Signatory to Louisville, Kentucky, petition on behalf of William Brockman.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Bijur, Martin. (1833 – 1882) Native of Prussia, Louisville, Kentucky, attorney and politician. Practiced law in partnership with Lewis N. Dembitz until 1864. Practiced law in partnership with Byron Bacon afterwards. Elected as a Republican to the 1865-1867 Kentucky General Assembly. “Death of Hon. Martin Bijur,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 1, 1882, p. 2; Report of the Fifth Annual Meeting of the American Bar Association, Held at Saratoga Springs, New York, August 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th, 1882 (Philadelphia: George S. Harris & Sons, 1883), 143-4.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-0865, KYR-0001-004-1375, KYR-0001-004-1379, KYR-0001-004-1388, KYR-0001-004-1409, KYR-0001-004-1566, KYR-0001-004-1987, KYR-0001-004-1988, KYR-0001-004-2030, KYR-0001-004-2839, KYR-0001-005-0051, KYR-0001-005-0142, KYR-0001-020-0323, KYR-0002-156-0004.

Bramlette, Thomas Elliott. (1817 – 1875) Twenty-third governor of Kentucky. Clinton County, Kentucky, native. Represented Clinton County in the state legislature in the 1840s. Judge of the Sixth Judicial Circuit at outset of the war. Resigned office to become colonel of Third Kentucky Volunteer Infantry U.S.A. Resigned commission in 1862 to become U.S. District Attorney for Kentucky. Elected governor in November 1863 over Charles A. Wickliffe and served until 1867. Ross A. Webb, “Thomas E. Bramlette (1863-1867)” in Lowell H. Harrison, ed., Kentucky’s Governors (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004), 93-97.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-001-0001, … [2,258 more at present].

Brockman, William. (c. 1824 – ?) Native of Germany and Louisville, Kentucky, resident. Laborer by trade. Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, District No. 1, p. 60.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0418, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0004-004-0823, KYR-0001-004-3258.

Brown, Jeff. (? – ?) Louisville, Kentucky, and New Albany, Indiana, attorney. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 43.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-0004-0016, KYR-0001-004-0018, KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0159, KYR-0001-004-0425, KYR-0001-004-0439, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-1418, KYR-0001-004-1712, KYR-0001-004-2939, KYR-0001-004-2944, KYR-0001-004-3407, KYR-0001-007-0591, KYR-0001-017-0332, KYR-0001-020-0333, KYR-0001-020-0712, KYR-0001-020-1422, KYR-0001-020-1499, KYR-0001-020-1575, KYR-0001-020-1617, KYR-0001-020-1618, KYR-0001-020-1812, KYR-0001-020-1823, KYR-0001-020-2056, KYR-0001-020-2113, KYR-0001-029-0063.

Burkhardt, Henry S. (? – ?) Louisville businessman. Worked in the wholesale grocery and commission merchant business at W. & H. Burkhardt, with William Burkhardt. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 47; J. D. Campbell’s Louisville Business Directory, For 1864 (Louisville: L. A. Civill, nd.),119.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Bush, Samuel S. (1830 – 1877) Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Partner in the firm of Bush & Shivell, along with Henry C. Shivell. Kentucky Marriages, 1797-1865, U. S. City Directories, 1821-1989 [database online, Ancestry.com; Edwards’ Annual Directory to the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business Firms, Etc., Etc., in the City of Louisville for 1865-6 (Louisville: Maxwell & Co., 1866), 234.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0439, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-1601, KYR-0001-004-2133, KYR-0001-020-0637.

Chrisler, Rudolph. (? – ?) Gave testimony in The Commonwealth v. William Brockman, tried in the Jefferson Circuit Court in 1864.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Clement, Joseph. (c. 1819 – 1882) New Hampshire native and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney and magistrate. History of the Ohio Falls Cities and Their Counties, Vol. 1 (Cleveland: L. A. Williams, 1882), 356; Kentucky, Death Records, 1852-1953 [database on-line via Ancestry.com], Jefferson County, 1882, p. 7.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0047, KYR-0001-004-0180, KYR-0001-004-0364, KYR-0001-004-0418, KYR-0001-004-0454, KYR-0001-004-0551, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-0920, KYR-0001-004-1193, KYR-0001-004-1418, KYR-0001-004-1957, KYR-0001-004-1968, KYR-0001-004-2270, KYR-0001-0004-2293, KYR-0001-004-2358, KYR-0001-004-2399, KYR-0001-004-2416, KYR-0001-004-2510, KYR-0001-004-2540, KYR-0001-004-2789, KYR-0001-004-2898, KYR-0001-004-3184, KYR-0001-004-3407, KYR-0001-005-0057, KYR-0001-005-0058, KYR-0001-005-0117, KYR-0001-006-0005, KYR-0001-020-0174, KYR-0001-020-0351, KYR-0001-020-1133, KYR-0001-020-1437, KYR-0001-020-1649, KYR-0001-020-1944, KYR-0001-020-2113, KYR-0001-029-0087, KYR-0001-029-0156, KYR-0001-029-0164, KYR-0001-031-0009, KYR-0001-033-0004, KYR-0001-033-0005, KYR-0001-033-0030.

Conn, T. Jackson. (c. 1826 – ?) Kentucky native and Jefferson County Court Clerk. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 60; Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, Louisville, Sixth Ward, p. 120.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0018, KYR-0001-004-0133, KYR-0001-004-0439, KYR-0001-004-0660, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-1055, KYR-0001-004-1283, KYR-0001-004-2337, KYR-0001-004-2789, KYR-0001-006-0084, KYR-0001-007-0489, KYR-0001-020-1527, KYR-0001-029-0156, KYR-0001-029-0307.

Craig, Edwin S. (c. 1820 – 1882) Commonwealth’s Attorney for the Seventh Judicial District until 1861. Practiced law in partnership with Robert J. Elliott. “Death of Judge E.S. Craig,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 27, 1882, p. 4; Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 64; Seventh Manuscript Census of the United States (1850), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, Louisville, District Three, p. 94.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0364, KYR-0001-004-0454, KYR-0001-004-0479, KYR-0001-004-0660, KYR-0001-004-0732, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-0843, KYR-0001-004-0957, KYR-0001-004-1957, KYR-0001-004-2192, KYR-0001-004-2404, KYR-0001-020-0134, KYR-0001-020-0552, KYR-0001-020-0554, KYR-0001-020-0869, KYR-0001-029-0239.

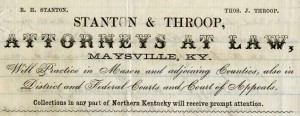

Dannecker, Frederick G. (1828 – ?) German native and New Albany, Indiana, attorney. John M. Scott, The Bench and Bar of Chicago (Chicago: American Biographical Publishing Company, 1883), 496-97; Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Indiana, Floyd County, New Albany, Third Ward, p. 8.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0685, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-1379, KYR-0001-004-1644, KYR-0001-004-1718, KYR-0001-004-2270, KYR-0001-004-2294, KYR-0001-004-2416, KYR-0001-004-3084, KYR-0001-004-3114, KYR-0001-004-3407.

DeFlour, [unknown]. (? – ?) Gave testimony in The Commonwealth v. William Brockman, tried in the Jefferson Circuit Court in 1864.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Dembitz, Lewis Naphtali. (1833 – 1907) Native of Prussia and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Delegate to the 1860 Republican national convention. Practiced law in partnership with Martin Bijur until 1864. Uncle of future Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis. “Dembitz, Lewis Naphtali” in The Encyclopedia of Louisville, ed. John E. Kleber (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001), 241-42.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-007-0109.

Donheimer, [unknown]. (? – ?) Gave testimony in The Commonwealth v. William Brockman, tried in the Jefferson Circuit Court in 1864.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

von Donhoff, Albert. (1806 – 1882) Native of Berlin, Germany, and Louisville, Kentucky, physician. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 75; “Dr. Albert Von Donhoff: The Unusual Life and Career of a Prussian Nobleman’s Son, and a Brilliant Physician” Louisville Courier-Journal, Nov. 7, 1882, p. 2.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Fields, Moses S. (c. 1828 – ?) Kentucky native and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, Louisville, Sixth Ward, p. 119.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-023-0117.

Frend, [unknown]. (? – ?) Gave testimony in The Commonwealth v. William Brockman, tried in the Jefferson Circuit Court in 1864.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Fry, Jack. (1839 – 1870) Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Practiced in partnership with Franklin Gorin in 1865. Edwards’ Annual Directory to the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business Firms, Etc., Etc., in the City of Louisville for 1865-6 (Louisville: Maxwell & Co., 1866), 310; “Jack Fry – Find A Grave Memorial” http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=86941179&ref=acom.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0439, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-1957, KYR-0001-004-2944, KYR-0001-020-0333, KYR-0001-020-1579, KYR-0001-023-0117.

Fry, William W. (c. 1798 – 1865) Virginia native and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, District 2, p. 18; “W.W. Fry – Find A Grave Memorial” http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=96183143&ref=acom.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0108, KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0180, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-020-0129, KYR-0001-020-0167, KYR-0001-020-1618, KYR-0001-029-0278.

Gailbreath, Joseph P. (? – ?) Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 97.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0024, KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-1418, KYR-0001-004-1983, KYR-0001-004-2416, KYR-0001-004-3407, KYR-0001-017-0352, KYR-0001-017-0355, KYR-0001-017-0356, KYR-0001-020-0828.

Gazlay, Addison M. (1818 – 1881) New York native and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Practiced in partnership with Franklin Gorin. History of the Ohio Falls Cities and Their Counties, Vol. 1 (Cleveland: L. A. Williams, 1882), 509-10; Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 98.

Associated Documents: KYR-001-004-0115, KYR-0001-004-0364, KYR-0001-004-0439, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-1791, KYR-0001-004-1803, KYR-0001-004-1805, KYR-0001-004-1806, KYR-0001-004-3407, KYR-0001-017-0001, KYR-0001-017-0062, KYR-0001-020-0129, KYR-0001-020-1527.

Gibson, Thomas Ware. (? – ?) Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 99.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0267, KYR-0001-004-0439, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-1509, KYR-0001-004-1528, KYR-0001-004-1553, KYR-0001-004-1554, KYR-0001-007-0109, KYR-0001-007-0229.

Gorin, Franklin. (1798 – 1877) Barren County, Kentucky, native and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Practiced in partnership with Addison M. Gazlay and with Jack Fry in 1865. E. Polk Johnson, A History of Kentucky and Kentuckians: The Leaders and Representative Men in Commerce, Industry and Modern Activities, Vol. III (Chicago and New York: Lewis Publishing, 1912), 1673-74; Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 102; Edwards’ Annual Directory to the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business Firms, Etc., Etc., in the City of Louisville for 1865-6 (Louisville: Maxwell & Co., 1866), 323.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0108, KYR-0001-004-0109, KYR-0001-004-0110, KYR-0001-004-0111, KYR-0001-004-0112, KYR-0001-004-0113, KYR-0001-004-0114, KYR-0001-004-0115, KYR-0001-004-0116, KYR-0001-004-0117, KYR-0001-004-0118, KYR-0001-004-0119, KYR-0001-004-0120, KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0122, KYR-0001-004-0123, KYR-0001-004-0124, KYR-0001-004-0139, KYR-0001-004-0364, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-1803, KYR-0001-023-0117, KYR-0002-204-0076, KYR-0002-204-0082.

Griffiths, Thomas J. (c. 1826 – 1884) Native of Wales and Louisville, Kentucky, physician. Practiced in partnership with Benjamin F. Grant. Accompanied an 1861 movement south of Louisville by General William T. Sherman, and provided medical services to the military barracks in Louisville through the end of the war. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 105; “Dr. Thomas J. Griffiths” The Louisville Medical News XVII no. 23 (June 7, 1884): 360-61; Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, Louisville, Eighth Ward, p. 320.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Hanna, John. (? – ?) Louisville, Kentucky, businessman. Partner in Hanna & Co., printers, with Alexander Hanna. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 111.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Harris, James. (? – ?) Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Edwards’ Annual Directory to the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business Firms, Etc., Etc., in the City of Louisville for 1865-6 (Louisville: Maxwell & Co., 1866), 339.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0083, KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-1418, KYR-0001-004-1644, KYR-0001-004-1957, KYR-0001-004-2270, KYR-0001-004-2510, KYR-0001-017-0352, KYR-0001-017-0355, KYR-0001-020-1579.

Hoke, William B. (1838 – 1904) Kentucky native and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Practiced in partnership with Samuel S. English. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 82, 123; Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Meeting of the Kentucky State Bar Association Held at Covington, Kentucky, June 22-23, 1905 (Louisville: George G. Fetter, 1905), 56; John J. McAffee, Kentucky Politicians: Sketches of Representative Corn-Crackers and Other Miscellany (Louisville: Courier-Journal Job Printing Co., 1886), 92-94.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0682, KYR-0001-004-0683, KYR-0001-004-0684, KYR-0001-004-0685, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-1377, KYR-0001-004-2161, KYR-0001-020-1598, KYR-0001-031-0125.

Hornsby, Isham H. (c. 1822 – ?) Kentucky native and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 125; Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, Louisville, Sixth Ward, p. 20.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Huber, [unknown]. (? – ?) Gave testimony in The Commonwealth v. William Brockman, tried in the Jefferson Circuit Court in 1864.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

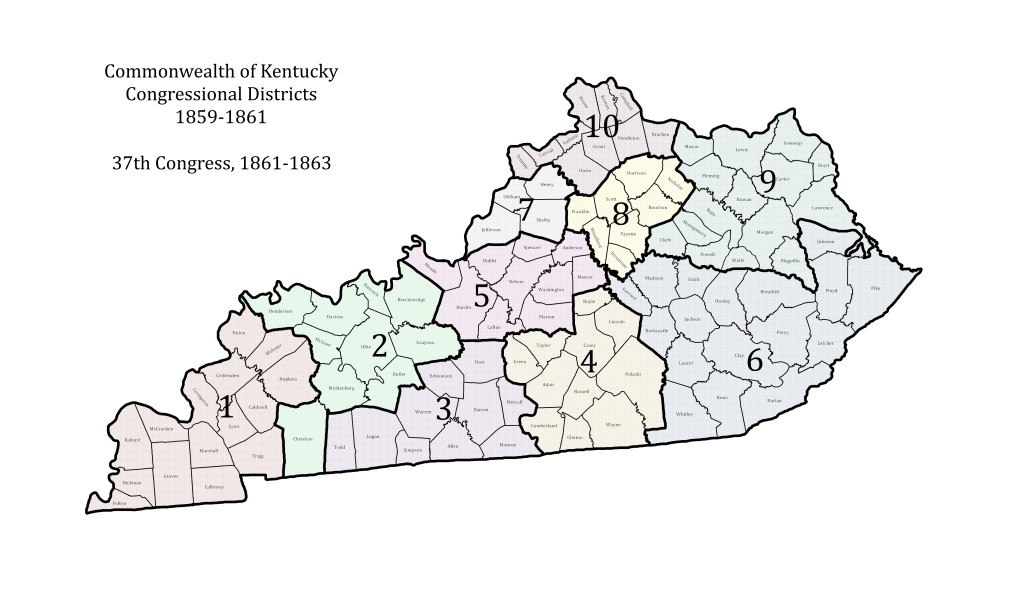

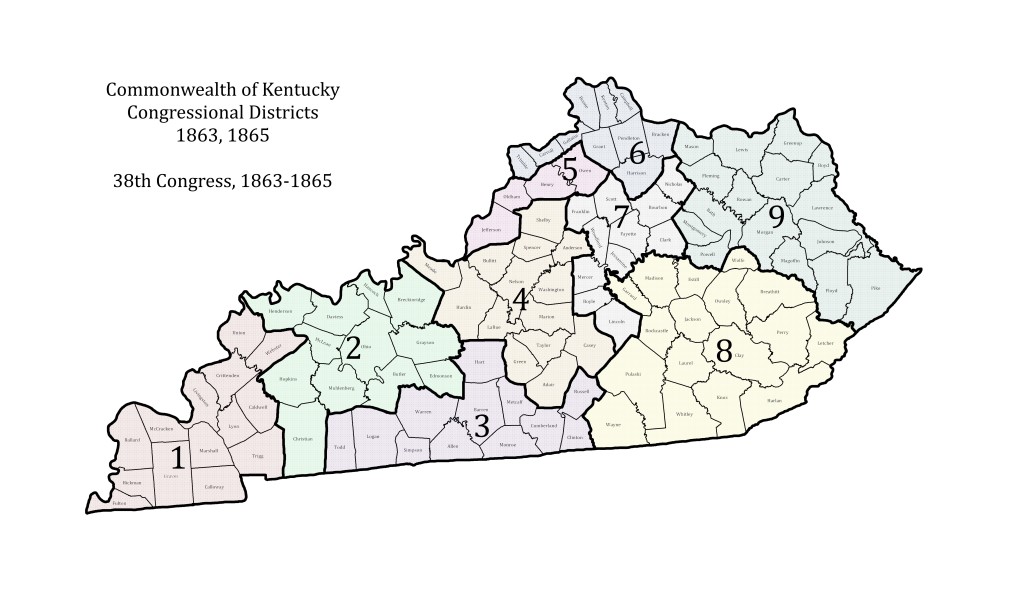

Jefferson Circuit Court. Part of the Seventh Judicial Circuit, which also included Bullitt, Oldham, Shelby, and Spencer Counties. Peter B. Muir (1861) and George W. Johnston (1862-1865) were the judges. Edwin S. Craig (1861) and J. R. Dupuy (1862-65) were the Commonwealth’s Attorneys. James P. Chambers was the Circuit Court Clerk.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0003, … [390 more at present].

Kahnt, Charles. (? – ?) Louisville, Kentucky, furniture maker. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 135.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Kramur, Franz. A. (? – ?) Signatory to Louisville, Kentucky, petition on behalf of William Brockman.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

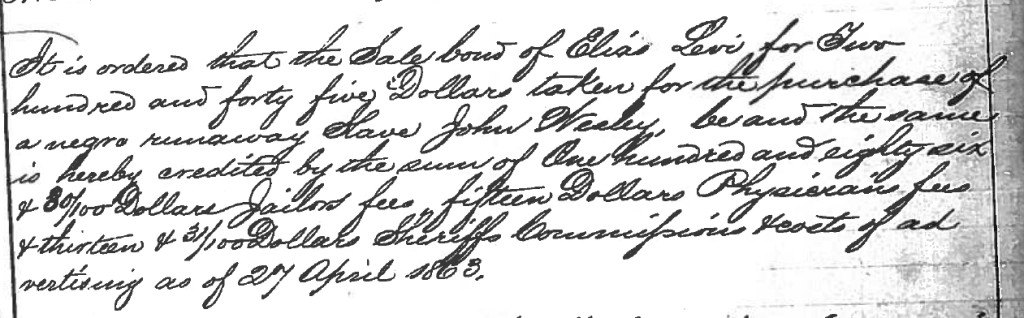

Logel, Adolph. (? – 1864) Killed in altercation with William Brockman in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1864.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Louisville, Kentucky. Seat of Jefferson County on the Ohio River. Largest city in Kentucky during the Civil War. “Louisville” in The Kentucky Encyclopedia, ed. John E. Kleber (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1992), 574-8. The Encyclopedia of Louisville, ed. John E. Kleber (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001).

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-001-0001, … [1,102 more at present].

Mattingly, John N. (? – ?) Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Practiced in partnership with Isaac R. Greene. Edwards’ Annual Directory to the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business Firms, Etc., Etc., in the City of Louisville for 1865-6 (Louisville: Maxwell & Co., 1866), 434, 327.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0180, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-0827, KYR-0001-004-0828, KYR-0001-004-2250, KYR-0001-004-2416, KYR-0001-004-3407, KYR-0001-005-0042.

McDowell, William Preston. (c. 1838 – ?) Kentucky native and Louisville, Kentucky, law clerk. Assisted in raising the Fifteenth Kentucky Volunteer Infantry Regiment and was appointed its adjutant. After August 1862, served as aide-de-camp and assistant adjutant general to Major General Lovell H. Rousseau. Wounded in action at the battle of Stones River. Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, Louisville, Fourth Ward, p. 74. Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Kentucky, National Archives and Records Administration, RG94, M397, Roll 284, Fifteenth Infantry, Hu-McE; J.H. Battle, W.H. Perrin, and G.C. Kniffin, The History of Kentucky, Eighth Edition, Part I (Louisville and Chicago: F.A. Battey, 1888), 839-40.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Meriwether, William A. (1825 – ?) Deputy U.S. Marshal from 1861 to 1864 and appointed U.S. Marshal for Kentucky in 1864. J.H. Battle, W.H. Perrin, and G.C. Kniffin, The History of Kentucky, Eighth Edition, Part I (Louisville and Chicago: F.A. Battey, 1888), 847.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-020-0927, KYR-0001-031-0109.

Miller, Isaac Price. (c. 1818 – ?) Kentucky native and Jefferson County, Kentucky, farmer. Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, District 1, p. 195; Miller-Thum Family Collection, 990PC47, Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Kentucky.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-023-0116, KYR-0001-004-0787.

Miller, John K. (? – ?) Signatory to Louisville, Kentucky, petition on behalf of William Brockman.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Oakland House and Race Course. Louisville, Kentucky, horse racing track established in 1832. Saw its heyday in the 1830s and 1840s, and closed in the 1850s. “Oakland Race Course” in The Encyclopedia of Louisville, ed. John E. Kleber (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001), 665.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0309, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0002-036-0045, KYR-0002-036-0046.

Ormsby, Collis. (1817 – 1891) Kentucky native and Louisville, Kentucky, merchant. Owner of the hardware and cutlery business of Collis Ormsby. Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, Louisville, Fifth Ward, p. 208; Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 189; Louisville Daily Journal, Jun. 22, 1861, p. 1.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0002-058-0006, KYR-0002-220-0147, KYR-0002-220-0149, KYR-0002-220-150.

Ormsby, Robert J. (1822 – 1879) Louisville, Kentucky, businessman. Bookkeeper in the hardware and cutlery business of Collis Ormsby. A founding director and stockholder of Cedar Hill and Oakland Railway Company in 1868. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 189; Acts of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky (Frankfort, Ky.: Kentucky Yeoman Office, John H. Harney, Public Printer: 1868), 553-554.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Pope, Alfred Thurston. (1842 – 1891) Kentucky native and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Kentucky Death Records, 1852 – 1953 [database online, Ancestry.com], Jefferson County, 1891; J.H. Battle, W.H. Perrin, and G.C. Kniffin, The History of Kentucky, Eighth Edition, Part I (Louisville and Chicago: F.A. Battey, 1888), 877-78.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0439, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-031-0215.

Pope, Hamilton. (1815 – 1894) Louisville, Kentucky native and attorney. Practiced in partnership with John G. Barrett. Commanded Louisville Home Guards that accompanied William T. Sherman on an expedition towards Muldraugh’s Hill in 1861. Thomas Speed, The Union Regiments of Kentucky (Louisville: Courier-Journal Job Printing Company, 1897), 24, 28, 427. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 196.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0139, KYR-0001-004-0364, KYR-0001-004-0439, KYR-0001-004-0448, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-2416, KYR-0001-004-3055, KYR-0001-007-0109, KYR-0001-007-0229, KYR-0001-007-0309, KYR-0001-009-0024, KYR-0001-017-0265, KYR-0001-020-0351, KYR-0001-020-0637, KYR-0001-020-1575, KYR-0001-031-0215, KYR-0001-033-0039, KYR-0002-060-0029, KYR-0002-060-0030, KYR-0002-067-0053, KYR-0002-204-0037, KYR-0002-218-0014, KYR-0002-218-0056, KYR-0002-218-0098, KYR-0003-158-0103.

Ronald, William A. (? – ?) Sheriff of Jefferson County in 1864-65. Stock agent for the Louisville and Nashville Railroad. J. D. Campbell’s Louisville Business Directory, For 1864 (Louisville: L. A. Civill, nd.),70; Edwards’ Annual Directory to the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business Firms, Etc., Etc., in the City of Louisville for 1865-6 (Louisville: Maxwell & Co., 1866), 502; Genealogical and Historical Notes on Culpeper County, Virginia (Culpeper, Va.: Raleigh Travers Green, 1900), 90; Louisville Daily Democrat, July 19, 1867, p. 1.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0180, KYR-0001-004-0233, KYR-0001-004-0234, KYR-0001-004-0235, KYR-0001-004-0748, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-1070, KYR-0001-004-1332, KYR-0001-004-1379, KYR-0001-004-1600, KYR-0001-004-1966, KYR-0001-004-2030, KYR-0001-004-2399, KYR-0001-004-2511, KYR-0001-004-2878, KYR-0001-005-0051.

Rousseau, Richard Hilaire. (1815 – 1872) Lincoln County, Kentucky, native and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Practiced in partnership with his brother, Lovell H. Rousseau. The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, Vol. XII (New York: James T. White, 1904), 185; Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 210.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0018, KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0180, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-0841, KYR-0001-007-0109, KYR-0001-020-0712, KYR-0001-023-0117, KYR-0001-034-0050.

Semms, [unknown]. (? – ?) Gave testimony in The Commonwealth v. William Brockman, tried in the Jefferson Circuit Court in 1864.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Sherley, Zachariah Madison. (1811 – 1879) Virginia native and Louisville, Kentucky, businessman. Owned and operated steamboats along the Ohio River, contracting many of them to the United States army during the war. Partner in the ship chandler firm of Sherley, Bell & Co. with Jesse K. Bell and Richard H. Woolfolk. “Sherley, Zachariah Madison ‘Zachary’” in The Encyclopedia of Louisville, ed. John E. Kleber (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001), 814; Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 224.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-007-0552, KYR-0001-020-1812, KYR-0002-205-0045, KYR-0002-207-0095, KYR-0002-207-0147, KYR-0002-209-0130, KYR-0002-220-0130, KYR-0002-221-0999, KYR-0002-221-1000, KYR-0002-221-1001, KYR-0002-221-1009, KYR-0003-158-0595, KYR-0003-158-0714.

Shivell, Henry C. (1841-1869) Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Practiced in partnership with Samuel S. Bush. President of a lead mine along the Kentucky River in Owen County, Kentucky in 1865. Edwards’ Annual Directory to the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business Firms, Etc., Etc., in the City of Louisville for 1865-6 (Louisville: Maxwell & Co., 1866), 529; New Albany Daily Ledger, February 27, 1866, 2; New Albany Daily Ledger, August 5, 1865, 2; The Louisville Daily Journal, April 12, 1867; Daily Courier, July 26, 1866.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0439, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-2155, KYR-0001-007-0381, KYR-0001-007-0432.

Shrader, Augusta. (? – ?) Gave affidavit in The Commonwealth v. William Brockman, tried in the Jefferson Circuit Court in 1864.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Shrader, John. (? – ?) Gave affidavit in The Commonwealth v. William Brockman, tried in the Jefferson Circuit Court in 1864.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Smith, Samuel B. (c. 1800 – 1866) Virginia native and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Practiced in partnership with Joshua F. Bullitt. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 46, 230; Eighth Manuscript Census of the United States (1860), Population Schedules, Kentucky, Jefferson County, District One, p. 32; “Death of Samuel B. Smith, esq.—Bar Meeting,” Louisville Courier, Dec. 15, 1866, p. 1.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-007-0476, KYR-0001-020-0327.

Tennessee. Sixteenth state to join the Union in 1796. Shares Kentucky’s southern border. Capital at Nashville.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-002-0001, … [162 more at present].

Wolfe, Nathaniel. (1808 – 1865) Virginia native and Louisville, Kentucky, attorney and politician. Practiced in partnership with Silas N. Hodges. Former Commonwealth’s Attorney and State Senator. Served in the House of Representative of the Kentucky General Assembly from 1859-1863. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 267. “Wolfe, Nathaniel” in The Kentucky Encyclopedia, ed. John E. Kleber (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1992), 962.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0351, KYR-0001-004-0439, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-0811, KYR-0001-017-0194, KYR-0001-017-0358, KYR-0001-017-0375, KYR-0001-017-0384, KYR-0001-020-0323, KYR-0001-020-0863, KYR-0001-020-1244, KYR-0001-020-1437, KYR-0001-023-0109, KYR-0001-029-0097, KYR-0001-031-0202, KYR-0001-033-0010, KYR-0002-050-0008, KYR-0002-207-0142, KYR-0002-218-0044, KYR-0002-218-0349, KYR-0003-158-0241.

Wood, Logan A. (? – ?) Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Practiced in partnership with L. A. Civill. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 267; “Lawyer L.A. Wood,” Louisville Courier-Journal, Dec. 3, 1886, p. 2.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-006-0049, KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0234, KYR-0001-004-0264, KYR-0001-004-0310, KYR-0001-004-0384, KYR-0001-004-0483, KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-004-1057, KYR-0001-004-1260, KYR-0001-004-1458, KYR-0001-004-1644, KYR-0001-004-1957, KYR-0001-004-2161, KYR-0001-004-2293, KYR-0001-004-2294, KYR-0001-004-2416, KYR-0001-004-2867, KYR-0001-004-2927, KYR-0001-004-3168.

Wood, William C. (? – ?) Louisville, Kentucky, attorney. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 267.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0113, KYR-0001-004-0114, KYR-0001-004-0117, KYR-0001-004-0121, KYR-0001-004-0122, KYR-0001-004-0123, KYR-0001-004-0124, KYR-0001-004-0787.

Wood, William F. (? – ?) Louisville, Kentucky, businessman. Partner in the wall paper and window shade business of Wood & Bros. with Charles A. and John B. Wood. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 267; Edwards’ Annual Directory to the Inhabitants, Institutions, Incorporated Companies, Manufacturing Establishments, Business Firms, Etc., Etc., in the City of Louisville for 1865-6 (Louisville: Maxwell & Co., 1866), 602.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787.

Woolfolk, Richard Henry. (1823 – 1885) Kentucky native and Louisville, Kentucky, businessman. Owned and operated steamboats along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Partner in the ship chandler firm of Sherley, Bell & Co. (later Sherley, Woolfolk, & Co.) with Zachariah M. Sherley and Jesse K. Bell. Tanner’s Louisville Directory, and Business Advertiser for 1861 (Louisville: Henry Tanner, 1861), 224, 268; “Capt. Woolfolk Dead,” Louisville Courier-Journal, Jun. 13, 1885, p. 3.

Associated Documents: KYR-0001-004-0787, KYR-0001-007-0552, KYR-0002-207-0095, KYR-0002-207-0147, KYR-0002-209-0026, KYR-0002-220-0130, KYR-0002-221-0999, KYR-0002-221-1000, KYR-0002-221-1001, KYR-0002-221-1009, KYR-0003-158-0595, KYR-0003-158-0714.

Have you found a hidden gem of a collection that you want to share with the world? Thinking of creative ways to actively engage your students in the work of history? Want to attract students to your department and develop diverse career skills for history majors?

Have you found a hidden gem of a collection that you want to share with the world? Thinking of creative ways to actively engage your students in the work of history? Want to attract students to your department and develop diverse career skills for history majors?

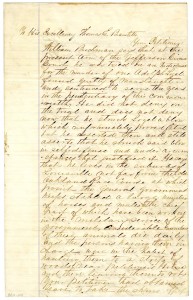

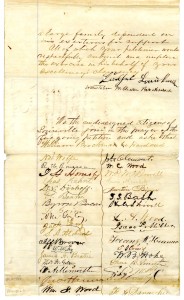

All of which your petitioner would respectfully submit and implore the exercise in his behalf of your Excellency’s clemency

All of which your petitioner would respectfully submit and implore the exercise in his behalf of your Excellency’s clemency