by Matthew C. Hulbert

On July 4, 1857, gunfire interrupted an Independence Day celebration in Green County. A lead ball exploded from the barrel of a musket. A man named Robert Peace had pulled the trigger. The projectile slammed into the midsection of one Felix Beauchamp. As a result of his wound, Beauchamp died momentarily thereafter. Following a jury trial, Peace found himself convicted of voluntary manslaughter and took up involuntary residence at the state penitentiary. In 1860, petitioners asked Governor Beriah Magoffin to pardon Peace.

***

Despite twelve pages of handwritten testimony given under oath by nineteen eyewitnesses to the death of Felix Beauchamp—no, thine eyes do not deceive, nineteen eyewitnesses—the above items are the only objective facts of the case passed down to us in the historical record. We don’t know with certainty what provoked the altercation; how much alcohol had been consumed in the lead up; what the parties involved said to each other in the seconds preceding the shooting; exactly how many shots were fired, their sequence, or from what distances.

Here’s a brief summation of each witness statement:

According to William M. Skaggs, he and another man named John Warf, an out-of-towner as it were, argued over the results of a ten cent card game. Peace allegedly confronted Skaggs, admonished him for quarreling with a guest, and accused Skaggs of having a rock in his pocket—apparently hinting that he would use it to assault Warf. In Skaggs’s version of events, Beauchamp then attempted to defuse the situation; but in doing so, he only angered Peace more, who challenged Beauchamp to a fight. Beauchamp refused the brawl and backed away, pulling a pistol from his coat in the process. Skaggs testified that he heard the report of a pistol, then heard Beauchamp say “don’t shoot,” and then may or may not have actually seen Peace shoot Beauchamp with a rifle. Skaggs also claimed that after Beauchamp fired the pistol, some of the other men at the gathering unsuccessfully tried to restrain Peace from shooting back. Peace then shot and killed Beauchamp.

John Warf’s version of the story matched Skaggs’s up to the moment of confrontation between Skaggs and Peace. As Warf told it, Beauchamp came to break up the argument and “caught hold of Peace around the body with both hands,” at which point “Peace slung Beauchamp loose from him.” Warf heard Beauchamp say “don’t shoot” or “something like it”—but never heard Peace challenge Beauchamp to fisticuffs.

Dr. Terrill agreed with the first two statements (Skaggs and Warf) that an argument between Skaggs and Warf led to a confrontation between Peace and Skaggs, which led to the fighting of Peace and Beauchamp. But in Terrill’s testimony, he “saw Peace punch at Beauchamp with his gun before either shot” but “would not State that the gun touched Beauchamp.”

William J. Graham agreed with the account of Dr. Terrill up to Peace trying to punch Beauchamp. Then, Graham contended, Peace said to Beauchamp: “you have a pistol in your pocket.” At that moment, Beauchamp’s hand was in his pocket. Graham saw Wesley Thompson and Mitchell Warren try to stop Beauchamp from shooting.

Mitchell Warren agreed with most of Graham’s testimony, but “did not see Wesley Thompson attempt to take hold of the gun.”

Pascal Warren told much the same story; he did see Peace sling Beauchamp and added that Beauchamp, at some point in the argument before the shooting, said “Bob you are wrong.”

According to William P. Warren, Peace aimed his rifle at Beauchamp, who replied with “don’t shoot me.” That prompted Peace to say “put up your darn little pistol then.” Beauchamp then jumped to the side of Peace’s muzzle and fired his pistol at very close range.

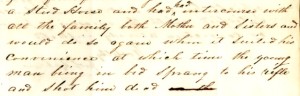

Joseph Warren testified that “a lady came down to where Beauchamp was lying after he was shot, and asked Peace what he killed him for, and Peace said. Darn him, he came up to me, and drew his pistol right in my face at first and afterwards fired at me—and Beauchamp said, do you hear him telling a lie.”

James and Calvin Skaggs both said they saw Beauchamp draw a pistol following his initial argument with Peace, but did not narrate the murder itself. James Skaggs testified that Peace did not punch at Beauchamp before or after the shooting.

William Peace Sr. alleged that Beauchamp drew his pistol on Peace, which prompted Peace to aim his rifle at Beauchamp. When Mitchell Warren tried to stop Peace, Beauchamp took the opportunity to fire first but missed. “Peace then fired immediately, the shots in quick succession, in about such quick succession, as a man fireing a double shot gun.”

Jacob Peace told a similar—if vaguer—story, but concluded that “this was all I saw, or heard, there were many others much closer than I was, and had a much better opportunity of seeing and hearing than I did—“

Burks Davis also described the argument and shooting in similar detail—but rather than Beauchamp being slung or Mitchell Warren being pushed away, it was Wesley Elkins that Peace “threw from him.”

John Warren’s testimony mirrored that of William P. Warren—but notes that “other things were said during the fracas, but witness [John Warren] don’t remember them.”

Renditions given by Josiah and Otawa Skaggs each essentially matched that of William Peace Sr.

William Peace Jr. and Joseph Peace both testified that Beauchamp drew his pistol first after Robert Peace said, “let me alone, I am not pestering you” to Beauchamp.

James Akin did not see the fight, but heard it from the stable. He was the only witness to state that “he had heard two other shots that evening, an hour or two before, but they were not in as quick succession.”

So what new can we glean from all of this eyewitness testimony? Unfortunately, the answer is just the realization that we know even less about what happened now than before.

Beauchamp may or may not have grabbed Peace before the shooting, and Peace may or may not have slung Beauchamp to the ground. Beauchamp may have approached Peace in a friendly manner or he may have grabbed Peace from behind with a revolver already in his hand. Peace may have challenged Beauchamp to a fight or he may or may not have simply attacked Beauchamp before any of the shooting started. Beauchamp may or may not have tried to shoot Peace while other men were intervening on his behalf. Each man may have told the other not to shoot. Peace might have told Beauchamp to raise his “darn little pistol” or alternatively said “let me alone, I am not pestering you.” Peace may have been holding his rifle in three or four different ways; and, it may have been Mitchell Warren or Wesley Thompson or both or neither that tried to wrestle guns away from Beauchamp and Peace at different times. The slug fired from Peace’s rifle may have killed Beauchamp on the spot—or Beauchamp may have lived long enough to tell an unnamed female witness that Peace was lying about the incident. Furthermore, Peace did and did not attempt to strike Beauchamp’s corpse with the rifle post-shooting, depending on which accounts we believe.

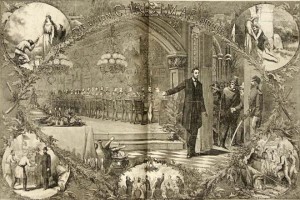

It probably shouldn’t surprise us that so many different men recounted an incident that probably all happened within the span of two or three minutes so variously—especially with alcohol undoubtedly involved. After all, this isn’t an unprecedented phenomenon when numerous people witness the same traumatic event. Despite him being on a stage directly in front of them, an entire audience of Washington theatergoers had trouble deciding what exactly John Wilkes Booth screamed after gunning down Abraham Lincoln. And throngs of witnesses failed to agree on how many shots were fired during the Kennedy assassination—as well as whether a second shooter had been perched on the now-notorious grassy knoll. Even in large gatherings where heinous crimes aren’t committed, such as the Gettysburg Address, witnesses frequently walk away having heard different things.

At first glance, what does seem surprising about this case is that in a society so prone to let men who killed other men with firearms walk on claims of “he fired first,” temporary insanity, alcoholism, or jealousy, a jury decided to ignore Robert Peace’s self-defense argument when one of the very few—if not the only—point agreed upon by all of the eye witnesses was that Felix Beauchamp drew and shot first. Even though some of the witnesses portray Peace in worse light than others, collectively, the testimony is inconclusive at best and seems hardly solid enough to justify a conviction. So how did Robert Peace end up in prison?

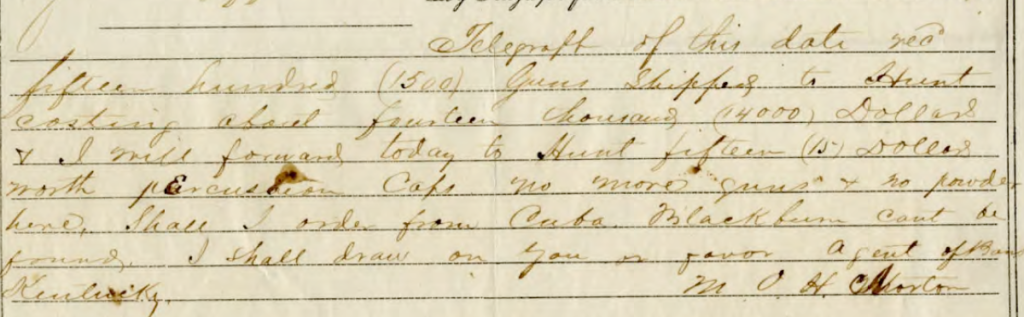

The shortest explanation is that Peace fell victim to the logistics of local court in the nineteenth century. The slightly longer one is that we should always remember the historical record (read: the statements of all nineteen witnesses) appears very differently—that is, complete and linear—to contemporary scholars than it did to a jury in real-time. And the much longer answer is that while many of the aforementioned witnesses apparently gave sworn testimony on paper in the form of affidavits, they “failed to obey the summons of the court” and did not appear in person. The judge overseeing the trial refused Peace a continuance that would’ve given these witnesses additional time to show up. Moreover, Peace’s lead attorney, Aaron Harding, “was suddenly called away by the extreme sickness of his wife and the death of a child.” In other words, Robert Peace learned the hard way that all the eye witnesses in the world make for a fantastic document in the CWG-K database, but are worthless if they don’t come to court.

Matthew C. Hulbert is an Assistant Editor of the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition.